M3 - Learner Manual

4. Tribes and Social Groups

Aboriginal peoples documented events, rituals and other aspects of culture in rock carvings and paintings in many locations throughout the country. Rock art in northern Australia clearly documents stories of some of the changes in Indigenous cultures throughout time.

|

|

Image: Petroglyph of male and female dancers, in Kuring-Gai Chase National Park, Sydney.

|

Even though we have this evidence of change over time, tribal groups and boundaries have largely remained the same, such as the locations of the Eora Nation, Wiradjiri Nation, Yuin Nation and so on.

Pre-1788 it is estimated that there were over 250 distinct Indigenous language groups in Australia, with various dialects within these groups. Today only around 120 of those languages are still spoken and many are at risk of being lost, as Elders pass away.

As Australian Indigenous cultures are oral cultures, language forms the basis for cultural transmission and cultural interchange, and so it is central to identity. Language has a central role in identifying where one comes from – who your people are. Cultural knowledge (ceremony, pathways through and tending country, medicine, etc.) is bound up in language.

Aboriginal peoples spoke some common language where borders met. This enabled trade of goods, negotiations for traverse and passage etc. and inter-tribal marriage. Today, those who speak traditional language, generally speak a range of local, languages where neighbouring language groups connect. This is also due to various language groups being moved off their traditional lands into present day ‘communities’.

|

|

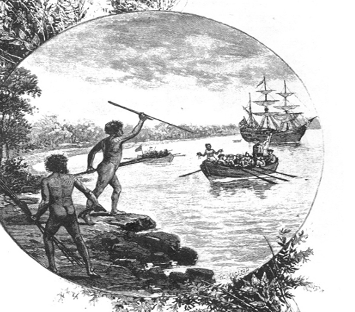

Image: A 19th-century engraving showing natives of the Gweagal tribe (Eora Nation) opposing the arrival of Captain James Cook in 1770.

|

In the 1700’s, there was no colonial understanding of the value and importance of language for cultural transmission. As with most colonised and invaded countries, Australian Indigenous people were actively and often violently, discouraged from speaking their languages. Children taken from their families, had little or no access to traditional language. This of course meant that many in following generations were not taught their traditional languages and so some languages became dormant, other have altogether gone.

Some people became partial speakers or spoke ‘broken-English’ or Creole. Thankfully, many place names and a few other names for animals, etc. have remained in use and more Aboriginal language names for significant places have been reinstated e.g. Uluru, Dja Dja Wurrung Country (in Central Victoria), Fraser Island had its name officially restored to K’gari (‘paradise’ in the Butchulla language). Lutruwita (Tasmania), Kinjarling (Albany in Western Australia).