M3 - Learner Manual

| Site: | Tranby National Indigenous Adult Education & Training |

| Course: | 11026NAT Diploma of Applied Aboriginal Studies 2024 |

| Book: | M3 - Learner Manual |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Wednesday, 4 February 2026, 2:38 PM |

Table of contents

- 1. Introduction: Module 3 - Connection to Country

- 2. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Similarities and Diversities

- 3. Kinship

- 4. Tribes and Social Groups

- 5. Language and Tribal Boundaries

- 6. Kinship in Contemporary Contexts

- 7. Personal and Work Relationships

- 8. Aboriginal Spirituality - Land and Sacred Sites

- 9. Creation Periods

- 10. Sacredness of Land and Daily Life

- 11. Totemism

- 12. Aboriginal Spirituality and Major World Religions

- 13. Aboriginal Peoples’ Alliance to Religions

- 14. Past, Present and Future Connected Through Ritual

- 15. References & Resources

1. Introduction: Module 3 - Connection to Country

NAT11026004 Interpret kinship and belonging to the land

PDF Module 3 Learner Manual Download

2. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Similarities and Diversities

Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nations and peoples share a common history of cultural development and colonial interactions and impact. There are however, differences in traditional boundaries, languages and customs.

One of the similarities is the structures of kinship. It is through kinship that identity is formed and grows meaning, through links which connect people to people (and groups) and people to country and the universe. It sets out connection and responsibilities to county and each other.

In mainland Australia, Indigenous people lived in semi-permanent / semi-nomadic lifestyles, centred around cultural maintenance responsibilities which reinforced their connection to land. They travelled with seasonal cycles, returning to the same locations tending to cultural responsibilities, hunting grounds and other food sources. Permanent villages were the norm for most Torres Strait Island communities.

Both similarities and differences run through many aspects of Indigenous cultures. These include language, appearance, land usage, the drawing of marriage lines, the handing down of responsibilities, spiritual beliefs and communication protocols.

As a brief example, some other similarities and diversities may include:

|

Similarities |

Diversities |

|

· ‘Family’ refers to extended family · rights and obligations are guided by kinship relationships within the family – less so in urban communities · communication protocols governed by kinship systems are similarly structured across the country · those who speak traditional languages, usually speak more than one traditional language · The terms ‘Aunty’ and ‘Uncle’ are used as a mark of respect · For English speaking Aboriginal people, there are English terms and turns of phrase which are distinctly Aboriginal e.g. deadly, cheeky, mob. |

· Aboriginal peoples live in a diverse range of areas (Traditional, remote, rural, suburban, urban) and engage in varying degrees of traditional and western behaviours and communication protocols. This can be at community, family or individual levels · There were hundreds of distinct languages · Some communities speak only traditional languages, some speak traditional languages and English, some speak only English · Each community has its own protocols. Though they may have some similarities there will always be differences |

3. Kinship

There are three levels of kinship in Australian Indigenous societies: Moiety, Totem and Skin Names.

A person's Moiety can be determined by their mother's side (matrilineal) or their father's side (patrilineal). Moieties can also alternate between each generation (people of alternate generations are grouped together).

People who share the same Moiety are considered siblings, meaning they are forbidden to marry. They also have a reciprocal responsibility to support each other.

The second level of kinship is Totem. Each person has at least four Totems which represent their nation, clan and family group, as well as a personal Totem. Nation, clan and family Totems are preordained, whereas personal Totems recognise an individual’s strengths and weaknesses.

Totems link a person to the universe - to air, water and geographical features. People don’t ‘own’ their Totems, rather they are accountable for them. Each person has a responsibility to ensure that their Totems are protected and passed on to the next generation.

Totems are split between Moieties to create a balance of use and protection. For example, while members of one Moiety protect and conserve the animal, members of the other Moiety may eat and use the animal.

The third level of kinship is the Skin Name. Like a surname, a Skin Name indicates a person’s blood line. It also conveys information about how generations are linked and how they should interact.

Unlike surnames, husbands and wives don’t share the same Skin Name, and children don’t share their parents’ name. Rather, it is a sequential system, so Skin Names are given based on the preceding name (the mother’s name in a matrilineal system or the father’s name in a patrilineal system) and its level in the naming cycle.

Each nation has its own Skin Names and each name has a prefix or suffix to indicate gender. There are 16-32 sets of names in each cycle. For example, in a matrilineal nation, if a woman with the first name in the cycle (One) has a baby, the child’s Skin Name will be the second name in the cycle (Two). All other ‘Twos’ in that community are now considered the sibling of that child, and all ‘Ones’ are considered their parents. When that child grows up and has children of their own, those children will be Threes. This sequential naming continues until the end of the number cycle is reached, then it begins again at One.

For further explanation of kinship structures go to the following YouTube videos:

An Example of Aboriginal Kinship Systems:

Country Kinship and Identity:

Family and Kinship:

4. Tribes and Social Groups

Aboriginal peoples documented events, rituals and other aspects of culture in rock carvings and paintings in many locations throughout the country. Rock art in northern Australia clearly documents stories of some of the changes in Indigenous cultures throughout time.

|

|

Image: Petroglyph of male and female dancers, in Kuring-Gai Chase National Park, Sydney.

|

Even though we have this evidence of change over time, tribal groups and boundaries have largely remained the same, such as the locations of the Eora Nation, Wiradjiri Nation, Yuin Nation and so on.

Pre-1788 it is estimated that there were over 250 distinct Indigenous language groups in Australia, with various dialects within these groups. Today only around 120 of those languages are still spoken and many are at risk of being lost, as Elders pass away.

As Australian Indigenous cultures are oral cultures, language forms the basis for cultural transmission and cultural interchange, and so it is central to identity. Language has a central role in identifying where one comes from – who your people are. Cultural knowledge (ceremony, pathways through and tending country, medicine, etc.) is bound up in language.

Aboriginal peoples spoke some common language where borders met. This enabled trade of goods, negotiations for traverse and passage etc. and inter-tribal marriage. Today, those who speak traditional language, generally speak a range of local, languages where neighbouring language groups connect. This is also due to various language groups being moved off their traditional lands into present day ‘communities’.

|

|

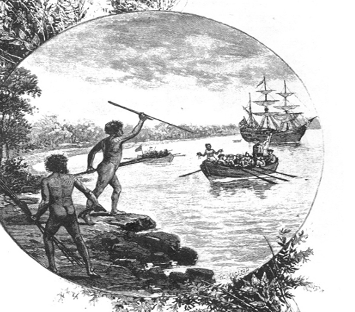

Image: A 19th-century engraving showing natives of the Gweagal tribe (Eora Nation) opposing the arrival of Captain James Cook in 1770.

|

In the 1700’s, there was no colonial understanding of the value and importance of language for cultural transmission. As with most colonised and invaded countries, Australian Indigenous people were actively and often violently, discouraged from speaking their languages. Children taken from their families, had little or no access to traditional language. This of course meant that many in following generations were not taught their traditional languages and so some languages became dormant, other have altogether gone.

Some people became partial speakers or spoke ‘broken-English’ or Creole. Thankfully, many place names and a few other names for animals, etc. have remained in use and more Aboriginal language names for significant places have been reinstated e.g. Uluru, Dja Dja Wurrung Country (in Central Victoria), Fraser Island had its name officially restored to K’gari (‘paradise’ in the Butchulla language). Lutruwita (Tasmania), Kinjarling (Albany in Western Australia).

5. Language and Tribal Boundaries

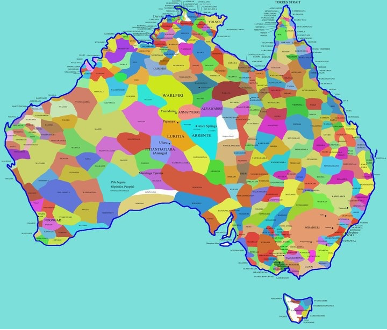

Figure 1: Map of Indigenous Tribal Groups in Australia

Created in 1994, the Aboriginal Australia map is an attempt to show the diversity of Australian Indigenous languages using sources available at the time. The information in the map is contested by some traditional landowners.

Source: https://aiatsis.gov.au/explore/articles/aiatsis-map-indigenous-australia

Today there are Aboriginal language centres and programs being developed to support keeping language and culture alive. In NSW, the Department of Aboriginal Affairs supports five Aboriginal Language and Culture Nests. These are:

· Bundjalung – East of (approximately) a line running from Grafton to the Qld boarder

· Gamilaraay/Yuwaalaraay – Area approximately bordered by Collarenebri, Walgett and Goodooga

· Gumbaynggirr – Mid NSW north coast – Area south of Grafton to Nambucca and inland to Dorrigo

· North West Wiradjuri – Areas around Dubbo – south to Peak Hill, east to Mudgee, North to Gilgandra and west to Trangie

· Paakantji/Baarkintji - includes the communities of Broken Hill, Wilcannia, Menindee, Bourke, Mildura and Coomealla.

You can access further information on each Nest at the following link:

https://www.aboriginalaffairs.nsw.gov.au/policy-reform/language-and-culture/nests

Consider the following question in preparation for your weekly Q&A sessions with your trainer:

Whilst there is a lot of discussion on the loss of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander verbal/oral language, are there other forms of language that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people use?

6. Kinship in Contemporary Contexts

Kinship structures and obligations are a defining part of many cultures throughout the world. Australian Indigenous kinship arranges clan groups and skin groups within a larger tribe. This puts everyone in a specific kinship relationship to everyone else and gives specific, governing everyday life such as food sharing and who can communicate with whom. On the coming of adulthood these practices are expected to be adhered to.

These structures define which relatives can talk to one another, and who should not be address directly. Partnering could change how people related to each other due to kinship taboos, such as sons-in-law and mothers-in-law being forbidden to speak or even have eye contact.

Kinship brought with it a set of obligations that one had to perform when relating to others. These obligations were not just part of the past, they are part of Aboriginal Lore and are still active in many parts of Australia today, especially in Dessert and Northern Australian communities.

Kinship is at the heart of Indigenous society. A person’s position in the kinship system establishes their relationship to others and to the universe, prescribing their responsibilities towards other people, the land and natural resources. Traditional kinship structures remain important in many Indigenous communities today.

Source: https://www.australianstogether.org.au/discover/indigenous-culture/kinship/

7. Personal and Work Relationships

Despite colonial history, Aboriginal kinship and family structures remain cohesive forces which bind Aboriginal people together in all parts of Australia. They provide psychological and emotional support to Aboriginal people.

Aboriginal family obligations are often seen as nepotism by non-Indigenous Australians. There can be some confusion where they are only partly observed. If there is inconsistency with how they are kept, it makes it look like they are being used as an excuse rather than as an obligation.

Personal and work relationships and status within Aboriginal communities are important, as they connect and reconnect people to relatives, broader tribal groups, and back into communities. They also are central to how people identify themselves. Today many people in urban, regional and rural setting often introduce themselves by their family group and then tribal affiliations.

Personal relationships can often impact work relationships. People are expected to declare involvement and relationship. for instance, if you are appointed to an interview panel, you are expected to declare any family ties, personal or business relationship as this may present a conflict of interest. With Indigenous people, second and third cousins are often viewed as part of the close network, which may confuse people who are not engaged directly in the community. This can create some complication and requires considerable finesse, when meeting obligations to family and meeting the rule of law and best practice at the same time.

Bureaucratic structures set up by non-Indigenous people and organisations (such as the government) often fail because they do not account for kinship structures and whose authority counts. Those set up in positions of authority can only really have an influence over related individuals.

8. Aboriginal Spirituality - Land and Sacred Sites

The following definition of Aboriginal spirituality gives some sense of the scale of spirituality in the lives of Australia’s first inhabitants:

Aboriginal spirituality is defined as at the core of Aboriginal being, their very identity. It gives meaning to all aspects of life including relationships with one another and the environment. All objects are living and share the same soul and spirit as Aboriginal peoples. There is a kinship with the environment. Aboriginal spirituality can be expressed visually, musically and ceremonially.

Reference: Grant, E.K., Unseen, Unheard, Unspoken: Exploring the Relationship Between Aboriginal Spirituality & Community Development. 2004, University of South Australia: Adelaide, pg. 8-9

The land and the stories are the teacher. Creation stories are like parables, they contain both moral and practical information such as kinship taboos, what to eat or not, passage to important places. Lessons are taught that are above the opinions of living people. The stories have authority in their antiquity and collective ownership.

9. Creation Periods

The Creation period, in many stories begins in darkness and the bare earth. Out of these Dreaming stories came great ancestral spiritual beings, who then travelled across a land without form and created sacred sites and other significant places, giving language to people, creating other living beings and shaping the earth. Many different creation stories exist among the different Aboriginal groups. This period of creation is often referred to as Alcheringa, Creation time, the ‘Dreaming” or the ‘Dreamtime’. The Dreaming was the time before time existed.

Click on the following link for Jacinta Koolmatrie TEDx Talk: The myth of Aboriginal stories being myths:

Different characters and beings, in Creation stories, created the land and the lore in ways particular to different peoples and landscapes.

The Dreaming refers not to historical past but a fusion of identity and spiritual connection with the timeless present.

10. Sacredness of Land and Daily Life

“For Aboriginal peoples, country is much more than a place. Rock, tree, river, hill, animal, human – all were formed of the same substance by the Ancestors who continue to live in land, water, sky. Country is filled with relations speaking language and following Law. No matter whether the shape of that relation is human, rock, crow, wattle. Country is loved, needed, and cared for, and country loves, needs, and cares for her peoples in turn. Country is family, culture, and identity. Country is self.” (Kwaymullina, 2005)

Connection to land is the core to identity and spirituality, these three things are intertwined. Maintaining land where there are Dreaming sites, bora rings, water holes, burial grounds, etc. is vital to the maintenance of culture.

Ceremonial activities assist Indigenous people in staying connected and keeping the spirit of the land alive through the process of being present and practicing culture.

Today access to traditional lands can be gained when native title is recognised but gaining this title is a lengthy, costly and complex process. The complexities of native title legislation mean that many applications are not successful.

11. Totemism

Rules and lore differ from one language group to another, depending on the environment and Dreaming stories or lore stories that belonged to that area. In lore, there are many rules associated with totems.

Some Aboriginal people may have several totems associated with animals, plants, landscape features and the weather. People who share the same totem have a special relationship with each other. Knowing a person’s totem means understanding a person’s relationship to the language group and to other people. Totems define people’s relationships to each other and give them particular rights, roles and restrictions within the language group.

Totemism is an integral feature of Indigenous spirituality and belief and best explained by the following quote:

A totem is a natural object, plant or animal that is inherited by members of a clan or family as their spiritual emblem. Totems define peoples' roles and responsibilities, and their relationships with each other and creation.

Totems are believed to be the descendants of the Dreamtime heroes, or totemic beings. Dreamtime heroes are linked to space and place. The places from which they emerged and travelled, and inter-acted with other spirit-beings, all become associated with the particular hero or heroes and are valued according to the importance of that part of creation to the local tribal group.

Each clan family belonging to the group is responsible for the stewardship of their totem: the flora and fauna of their area as well as the stewardship of the sacred sites attached to their area. This stewardship consists not only of the management of the physical resources ensuring that they are not plundered to the point of extinction, but also the spiritual management of all the ceremonies necessary to ensure adequate rain and food resources at the change of each season.

A typical boy’s story might begin before he is even born. As his mother becomes conscious of his first movement in the womb she immediately has to take note of the area so that the infant will become identified with the spirit of the particular area in which she is located. This is based on the belief that the spirit of that area has energised the infant in the womb and the child becomes inextricably linked with the spirit associated with the dominant creation of that place, as his conception totem.

Source: https://www.australianstogether.org.au/discover/indigenous-culture/aboriginal-spirituality

12. Aboriginal Spirituality and Major World Religions

There has been continuous Christian missionary presence in Aboriginal communities since 1821. This has seen many Indigenous people convert to Christianity, first through force, then coercion and later through consent. This was done with an implied assumption that Indigenous people had no religion or spirituality. ‘Spirituality is a broader term than religion, understood as more diffuse and less institutionalised than religion’ (Mikhailovich and Pavli, 2011)

Indigenous spirituality is different from religions such as Judaeo-Christian, Islam, Hindu. Indigenous spirituality does not worship a godhead or gods, instead it speaks to the inter-connectivity of people to the earth and the Dreaming and uses totems as a reflection of their everyday life and responsibilities to culture.

Judaeo-Christian, Islam, commonly known as the Abrahamic religions

An Abrahamic religion is a religion whose beliefs stem from the prophet Abraham and his descendants. The best known Abrahamic religions are Judaism, Christianity and Islam. These are all monotheistic (one God) religions.

Islam, Judaism, and Christianity are considered Abrahamic religions. This means that they all worship a single God as described by Abraham. Because of language differences, they call God by different names, but they are one and the same. Adherents of the three faiths believe that there are prophets that God has sent to teach the people.

Consider the following question in preparation for your weekly Q&A sessions with your trainer:

Church missions have played a significant role across the country as far as addressing the needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. What role/s have they played?

|

Australian Indigenous Spirituality and the major Religions - A Comparison |

||||

|

|

Indigenous Spirituality/Religion |

Judaeo-Christian |

Islam |

Hindu |

|

Organisational Structure |

All clan groups have key people who are keepers of stories and creation stories and maintain connection or contact with the Creation spirits through cultural practice. Certain Elders for instance are keepers of specific stories or rituals, with responsibilities for cultural maintenance broken down into men’s business and women’s business. Indigenous spirituality is broader than a religion.

|

The term Judeo-Christian groups Judaism and Christianity, either about Christianity's derivation from Judaism or due to perceived parallels or commonalities shared between the two traditions. ... The term "Abrahamic religions" is used to include, Christianity, Judaism and Islam

· Catholic means “Universal” · Judaism means” from/ of Judah’’ the old name for Israel |

Islam places emphasis on the individual’s relationship with God. The framework for this relationship follows the guidelines set out by the Qur’an and Sunnah. This relationship, in turn, defines a Muslim’s relations with everyone, which brings about justice, organization, and social harmony. In many Islamic countries the government, justice and law-making is directly related to the teachings of Islam Islam means "submission" (to the will of God)

|

Western cultures refer to Hinduism like other faiths is appropriately referred to as a religion. In India the term dharma is preferred, which is broader than the western term religion. Hinduism is a polytheism (many gods) rather than the Judeo-Christian monotheism (one God only) Hindu (or Indu) means sea and is from the Sanskrit word for the Indus river. ‘Hindu’ was used by Greeks to denote the country and people living beyond the Indus river. |

|

Key Beliefs

Key Beliefs

Key Beliefs

|

The earth is eternal, and so are the many ancestral figures / beings who inhabit it. These beings are often associated with particular animals, for example Kangaroo-men, Emu-men or Bowerbird-women. As they journeyed across the face of the Earth these powerful beings created human, plant and animal life; and they left traces of their journeys in the natural features of the land. They also connected particular groups of people with particular regions and languages. Some groups held belief in a supreme being – Biami, The Lightening Brothers, Wandjina The Dreaming continues to control the natural world.

Spiritual practice is linked to country through everyday life, ceremony and ritual. This is manifest in the landscape rather than as words in unchangeable text. The land and the stories are the teacher. |

All Judeo-Christian religions hold the 10 commandments at the core of their beliefs. Judaism focuses on the relationships between the Creator, mankind, and the land of Israel. Judaism does not have formal mandatory beliefs (other than the 10 commandments) but looks to 13 principles of faith: · God exists · There is only one God · God is incorporeal (not flesh but spirit) · God is eternal · Prayer is to be directed to God alone and to no other · The words of the prophets are true · Moses' prophecies are true, and Moses was the greatest of the prophets · The Written Torah (first 5 books of the Bible – The Old Testament) and Oral Torah (teachings now contained in the Talmud and other writings) were given to Moses · There will be no other Torah · God knows the thoughts and deeds of men · God will reward the good and punish the wicked · The Messiah will come · The dead will be resurrected Though there are some similarities between Judaism and Christianity, followers of the Christian religion base their beliefs on the life, teachings, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, written in the Gospels – The New Testament. Like Jews, Christians believe in one God that created heaven, earth and the universe. Christians believe Jesus is the "Messiah" or saviour of the world. In contrast, Jews believe the Messiah is yet to come. Christianity teaches that we are all born as sinners (original sin) where Jews believe that we are all born pure and free from sin.

|

Muslims believe that Islam is the complete and universal version of a primordial faith that was revealed many times before through prophets including Adam, Abraham, Moses and Jesus. Muslims consider the Quran to be the unaltered and final revelation of God. Muslims have six main beliefs · Belief in Allah as the one and only God · Belief in angels · Belief in the holy books (this includes the Judaio-Christian text - The Old Testament) · Belief in the Prophets. e.g. Adam, Ibrahim (Abraham), Musa (Moses), Dawud (David), Isa (Jesus) · Mohammed is believed to be the last law bearing prophet sent by God · Belief in the Day of Judgement · Belief in Predestination The formal beginning of the Muslim era was in 622 CE. Therefore, the year 2000 (based on the Gregorian calendar derived from the birth of Jesus as being year 1) was the Islamic year 1378. Based on a lunar calendar with days lasting from sunset to sunset Islamic holy days fall on fixed dates of the lunar calendar, which means that they occur in different seasons in different years according to the Gregorian calendar. |

· Dharma (righteousness, ethics) is considered the foremost goal of a human being in Hinduism. The concept Dharma includes behaviours that are considered to be in accord with Rta - the order that makes life and universe possible· Truth is eternal · Brahman is Truth and Reality · The Vedas are the ultimate authority · Everyone should strive to achieve dharma · Individual souls are immortal · Individual souls are repeatedly reincarnated until achieving moksha · The goal of the individual soul is moksha. Major scriptures include the Vedas and Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita, and the Agamas Prominent themes in Hinduism include the four Puruṣārthas, the proper goals or aims of human life, namely: · Dharma (ethics/ duties) · Artha (prosperity/ work) · Kama (desires/ passions) · Moksha (liberation/ freedom/ salvation) · karma (action, intent and consequences) · Saṃsāra (cycle of life, death and rebirth) · various Yogas (paths or practices to attain moksha) |

|

Practices, Rituals and Festivals

Practices, Rituals and Festivals

Practices, Rituals and Festivals |

· Ritual ceremonies involving special sacred sites, song cycles accompanied by dance, and body painting, and even sports, invoke these mythic and living beings and continue to provide the means to access the spiritual powers of The Dreaming · Smoking is used for spiritual cleansing · At important stages of men and women’s lives, ceremonies are held to seek the assistance of spiritual beings. This makes them direct participants in the continuing process of the Dreaming · Other ceremonies are known as increase rites, in which the willingness of ancestral beings to release the land’s fertility depends upon humans · Smoke is used for cleansing Recent years have seen major modern Indigenous festivals emerge. Some of these are celebrated nationally, they include: · Stompin’ Ground · Yeperenye Dreaming · Barunga Festival · Laura Festival · NARLA Knock Out · Survival · Coming of the Light · CROC Eisteddfod · NAIDOC · Reconciliation Week.

|

Judaic: · Various dietary restrictions and requirements, e.g. no eating pig meat, kosher preparation and production for foods and beverages and the slaughter of animals · Covering the head is an act of respect for God – especially during prayer, with a skull cap (yarmulke) · Male circumcision (brit milah) · Bat Mitzvah – at age 13 (12 for girls) becoming responsible for observing the 10 commandments · Shabbat – Saturday is day of rest - spent with family · Yom Kippur – annual day of atonement, a fasting day · Chanukkah - Many non-Jews consider this as the Jewish Christmas a there is elaborate gift-giving and decoration Catholicism’s 7 Sacraments: · Baptism – usually as an infant · Confirmation – at age 12 · Confession · Holy communion · Marriage · Taking Holy Orders · Unction (Anointing of the Sick) This follows on to receiving the Last rites – at death Burning of incense is used for spiritual cleansing Many of the other branches of Christianity have similar practices/ rituals. Christian Festivals/ Celebrations · Christmas –the birth of Jesus · Lent – fasting etc. 6 weeks leading up to Easter · Easter–The death and resurrection of Jesus |

· Various dietary restrictions and requirements, e.g. no eating pig meat, halal is the strict Islamic specification for the slaughter and raising of animals and preparation of meat for eating. Kosher and halal methods of animal slaughter are very similar, making kosher meat acceptable to Muslims · Shahada, the declaration of faith · Salat, - prayers - five times a day · Zakat – charity -alms-giving. · Sawm - fasting such as in Ramadan · Hajj, the annual pilgrimage to Mecca · Ritual purity in Islam, an essential aspect of Islam · In pictures: Hajj · male circumcision (Khitan) |

· Hindus are vegetarian · Cows, in particular are sacred and must never be harmed in any way · Puja – worship that includes regular ritual and recitation usually with offerings of food, flowers, etc. · meditation · family-oriented rites of passage · many annual festivals (some examples below) · occasional pilgrimages. Some Hindus leave their social world and material possessions, to engage in lifelong Sannyasa (monastic practices) to achieve Moksha. Festivals · Diwali (the festival of lights) is the best known · Holi · Navaratri (celebrating fertility and harvest) · Raksha Bandhan (celebrating the bond between brother and sister) · Janmashtami (Krishna's birthday) · Festival days for the many Gods and Goddesses, mean that most days of the year hosts a celebration/ veneration · Many people align themselves with particular Gods or Goddesses or group of deities to practice their primary devotion |

13. Aboriginal Peoples’ Alliance to Religions

The continuous Christian missionary presence in Aboriginal communities since 1821 has seen many Aborigines convert to Christianity. Indigenous communities across Australia’s Top End had contact with the Muslim Macassan traders for many centuries before British settlement. In the 1996 Australian census, more than 7000 respondents indicated that they followed a traditional Aboriginal spiritual belief. (Source: ABC, 2018)

Aboriginal people’s alliance to religions has come about through the interactions and exposure to non-indigenous people their religions and customs.

Aboriginals and Muslims

It’s a little-known fact that Muslim visitors first arrived in Australia well before the British established a colony in 1788. From at least as early as 1650, Muslim fishermen from Makassar in Indonesia made annual trips to Australia's far north coast in search of sea cucumbers—or trepang—which are highly valued in Chinese medicine and cooking. Indigenous Australians also journeyed to Indonesia, trading tortoise shells, tools, tobacco and other goods.

According to Dr John Bradley from Melbourne's Monash University, the Makassans represent Australia's first major, successful attempt at international relations. ‘They traded together. It was fair; there was no racial judgement, no race policy,’ he says.

You have faith, you have faith in the almighty, the all-powerful. They can plan but only God is the greatest of planners. If God has destined me to be what I want to be or do what I want, nothing can stop Allah's plan.

Anthony Mundine, World Champion boxer

Muslim Makassans and Australian Aborigines traded more than just goods; they also exchanged religious ideas.

Throughout Australia, Aboriginal peoples have married into families from other spiritual and religious belief, for instance, at Woolgoolga on NSW North Coast where 10% of the population practice Sikhism. Aboriginal people’s worldviews have changed and have been shaped by their interactions with other cultures and religions. Other religious belief systems do not replace Aboriginal spiritual belief but sit alongside it. Aboriginal peoples belong to the land and their spirituality and identity stem from this continuous connection, irrespective of other influences.

14. Past, Present and Future Connected Through Ritual

Australian indigenous spiritual belief is not separate from other aspects of life, culture and history. It is also difficult to speak of origins because an indigenous conception of time connects past actions and people with present and future generations. Time is circular, not linear, as each generation relives the Dreaming activities. Indigenous people maintain their connection through the daily process of being Indigenous. The concept of circular time collapses past, present and future into a continual present.

Rituals form part of spiritual responsibility - Obligation to country and maintaining continuity through spirituality happens in the present, honours the past (ancestors) and maintains continuity for future generations.

Festivals, celebrations, protests and gatherings such as the Knockout – often referred to as the new corrobboree, are practices that continue to maintain culture in urban and regional communities.15. References & Resources

References

'Seeing the Light: Aboriginal Law, Learning and Sustainable Living in Country', Ambelin Kwaymullina, Indigenous Law Bulletin May/June 2005, Volume 6, Issue 11

Research paper by Dr Marion Maddox, Consultant, Social Policy Group

"Indigenous Religion in Secular Australia", 14 December 1999.

Freedom of Religion, Belief, and Indigenous Spirituality, Practice and Cultural Rights. Paper prepared for the Australian Institute by the Centre for Education, Poverty and Social Inclusion, Faculty of Education, University of Canberra, Katja Mikhailovich Ms. Alexandra Pavli, 2011,

https://aifs.gov.au/publications/families-and-cultural-diversity-australia/3-aboriginal-families-australia

www.globaldialoguefoundation.org/files/traditionalfaiths&beliefs.pdf

Other Resources:

Aboriginal Elder: “The land owns us”

Bob Randall, a Yankunytjatjara elder and traditional owner of Uluru (Ayer’s Rock), explains his connectedness to the land and how every living thing is connected to every other living thing.

Essie Coffey's My Survival as an Aboriginal

Essie Coffey's classic documentary MY SURVIVAL AS AN ABORIGINAL was filmed in Brewarrina, far north-west New South Wales, Australia in 1978.

Useful Websites

Community based organisations

· Gadigal Information Service (Koori Radio 93.7fm) www.gadigal.org.au

· Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Lands Council (Sydney) www.metrolalc.org.au

· NSW Aboriginal Land Council www.alc.org.au

Education

· Tranby Aboriginal College www.tranby.edu.au

Health Related

· Aboriginal Health & Medical Research Council www.ahmrc.org.au

· Australian Indigenous Health Infonet www.healthinfonet.ecu.edu.au

· Australian Institute of Health & Welfare www.aihw.gov.au/publications/index.cfm/title/10583

· Close the Gap Oxfam Report (2008) www.closethegap.com.au

· National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation www.naccho.org.au

Government Departments & Agencies

· Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies www.aiatsis.gov.au

· Indigenous Coordination Centre www.indigenous.gov.au

· NSW Department of Aboriginal Affairs www.daa.nsw.gov.au

NSW Department of Health http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/search/search.asp?qText=Aboriginal+&Go=Go&collection=wwwsite&queryMode=kword

- Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies www.aiatsis.gov.au

- Indigenous Coordination Centre www.indigenous.gov.au

- NSW Department of Aboriginal Affairs www.daa.nsw.gov.au

- NSW Department of Health http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/search/search.asp?qText=Aboriginal+&Go=Go&collection=wwwsite&QueryMode=kword

· Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies www.aiatsis.gov.au

· Indigenous Coordination Centre www.indigenous.gov.au

· NSW Department of Aboriginal Affairs www.daa.nsw.gov.au

· NSW Department of Health http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/search/search.asp?qText=Aboriginal+&Go=Go&collection=wwwsite&queryMode=kword

Other general

· Australians for Native Title and Reconciliation www.antar.org.au

· Koori Mail www.koorimail.org

· National Directory of Aboriginal Business and Community Enterprises www.blackpages.com.au

· National Indigenous Times www.nit.com.au

· National Sorry Day Committee www.nsdc.org.au

Community based organisations

- Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council (Sydney) www.metrolalc.org.au

- NSW Aboriginal Land Council www.alc.org.au

- Gadigal Information Service (Koori Radio 93.7FM) www.gadigal.org.au