M2 - Learner Manual

| Site: | Tranby National Indigenous Adult Education & Training |

| Course: | 11026NAT Diploma of Applied Aboriginal Studies 2024 |

| Book: | M2 - Learner Manual |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Wednesday, 4 February 2026, 4:10 PM |

Table of contents

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Eighteenth Century Perspective

- 3. Draft Instructions for Governor Phillip, 25 April 1787

- 4. Contemporary Australian Perspective

- 5. The Impact of Native Title

- 6. Continuing Shift in Perspectives

- 7. Protection and Assimilation

- 8. Government Reserves, Missions and Stations

- 9. The Stolen Generation

- 9.1. The First Removals

- 9.2. Kevin Rudd’s Apology to the Stolen Generation

- 9.3. Rationale of the Government of the Time

- 9.4. Effects on Kinship Structures

- 9.5. Stolen Generation and Coping Mechanisms

- 9.6. Reuniting Families

- 9.7. The Stolen Generation - Rights and Responsibilities

- 9.8. Statistics

- 9.9. Housing

- 9.10. Health

- 9.11. Mortality rates

- 9.12. Life Expectancy

- 9.13. Child Mortality

- 9.14. Physical and Mental Health

- 9.15. Education and Employment

- 9.16. Employment

- 9.17. Early Childhood Education

- 9.18. School Attendance

- 9.19. Literacy and Numeracy

- 9.20. Year 12 Attainment

- 9.21. Family and Community Wellbeing

- 9.22. Incarceration

- 9.23. Interpreting Statistical Indicators

- 9.24. Comparisons -Indigenous and Non-Inidgenous Disadvantage

- 10. Indigenous Resistance

- 11. Aboriginal Rights and Civil Rights

- 12. References

1. Introduction

11026NAT Diploma of Applied Aboriginal Studies

Click the following link to download a printable version of Module 2 Learner Manual

Module 2 - Invasion:

Colonial Policies and Survival

NAT11026001 Analyse the impact of invasion and genocide

NAT11026003 Analyse protection and assimilation policies and practices

NAT11026009 Evaluate disadvantage in colonised Indigenous nation

Throughout this manual there are activities entitled “Pause for thought”. They are opportunities for you to take a moment to think about a specific question in relation to the content being considered. You are not required to submit them for assessment.2. Eighteenth Century Perspective

Terra nullius: A concept in international law meaning 'a territory belonging to no-one' or 'over which no-one claims ownership'. The concept is related to the legal acceptance of occupation as an original means of peacefully acquiring territory. However, a fundamental condition of a valid occupation is that the territory should belong to no-one. The concept has been used to justify the colonisation of Australia. The High Court decision of 1992 rejected terra nullius and recognises Indigenous native title.

Source: https://australianmuseum.net.au/glossary-indigenous-australia-terms

Eighteenth Century Perspective

The Eighteenth century saw the increasing expansion of the British Empire, who occupied roughly one third of the, then known world, often resulting in great hardship to the local Indigenous peoples. This was colonialism. In the case of Australia, Britain sought to extend its authority and empire into new regions, generally with an aim of ‘developing’ or exploiting other lands, resources and their peoples, often by force and oppression.

The term Terrra Nullius was not used by the 18th century colonisers. This term came into use quite recently (1960's - 70's) and has been taken on as it clearly describes the attitude of the time. At the time they used terms like, ‘discovery’ and ‘settlement’. The colonisers were directed to leave it all alone if the land was ocupied. To the colonisers, they were following a convention of international law of the time. The land was not occupied or settled in a ‘European way’ – with houses, towns, cultivated land, roads and no government as the British understood it to be, therefore it was fair game.

Though there were obviously people here they did not have what the British understood as 'claim' to the land. Though indigenous peoples were acknowledged they were not considered as British subjects.

The removal of Aboriginal people from their traditional lands and families, exploitation of Aboriginal labour, and gradual introduction of policy sought to control or contain Aboriginal people, was the fallout from the false concept of Terra Nullius.

3. Draft Instructions for Governor Phillip, 25 April 1787

Britain included the following instruction to Phillip, concerning the treatment of Aboriginal people. There is evidence that Phillip initially attempted to comply, although sometimes he had to resort with kidnapping ‘to conciliate their affections’. It is certain that land grants and military operations were far from conciliation. The particular instruction, which Britain repeated to other incoming Governors for their tour of duty, can be seen as empty rhetoric, mere window dressing for forcible occupation, where all land belonged to the Crown:

'You are to endeavour by every possible means to open an intercourse with the natives and to conciliate their affections, enjoining all our subjects to live in amity and kindness with them; and if any of our subjects shall wantonly destroy them, or give them an unnecessary interruption in the exercise of their several occupations, it is our will and pleasure that you do cause such offenders to be brought to punishment according to the degree of the offence'.

The draft instructions make no mention or acknowledgment of Aboriginal prior possession, and allowed Phillip’s right to make grants of ‘Crown’ land to whomever he chose, notably excluding the Aboriginal people whose land it was. Thus, Britain’s intent was clear from the first day of the invasion, that Aboriginal people had no rights to their homelands. Perhaps the thought was that Britain could assimilate Aboriginal people into British ‘civilisation’ through ‘conciliation’. The violent racial consequences over the next one hundred and fifty years were therefore inevitable. An obdurate Britain would not resile from its Imperial imperative to invade and control, not in Australia, not anywhere. We live with the outcome of those flawed policies today, where Aboriginal people generally remain marginalised, discriminated against in the Australian Constitution, and the denial of genocide continues as a political and public mantra.

Source: Gibbons, Ray. The Political Uses of Australian Genocide - the Role of Captain Arthur Phillip Reprised (Oct 2015)

4. Contemporary Australian Perspective

Contemporary Australian perspective debunks a lot of the myths that have been long held about Aboriginal people and culture, with Aboriginal people themselves asserting their identity and culture through arts, sports, education, business, community enterprise and politics. This is now reflected in what is taught at school about Aboriginal people, as well as the government’s inclusion and efforts.

Whilst poverty and poor health remain a feature, Aboriginal people have been fighting to change the conditions and narratives around their peoples. This has meant that they have been actively engaged in policies, and services, to and for their own people. This coincides with more Aboriginal people beginning to access better health services and education.

Today Aboriginal people can be seen all over Australia engaging in many walks of life and professions, as well as increasingly engaging in mainstream economy and society. This does not mean that they have forfeited their culture or identity.

5. The Impact of Native Title

Native Title has changed history and the way people interact with Traditional Owners in this country. This has meant the government, corporate and mining interests seeking to develop and work on Indigenous lands must consult with the local Traditional Owners. Native Title recognises the traditional rights and interests to land and waters of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Under the Native Title Act 1993 (NTA), Native Title claimants can make an application to the Federal Court to have their Native Title recognised by Australian law.

Why is this historical? Quite simply because Indigenous people in this country were not formally recognised as the owners of their own land and country, and the Mabo decision changed all this, in many respects Indigenous people can have a say in what happens on their land, however, this is restrictive and limits Indigenous peoples’ rights.

Following European arrival in Australia, the land rights of Indigenous Australians and their relationship with country were not recognised. The land was deemed terra nullius, Latin for ‘nobody’s land’, a legal doctrine which dictated that land which is recognised as unclaimed or unoccupied can be acquired by occupation.

For the next two centuries the ancestral land of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples was taken and many families were forcibly removed.

Source: https://www.sbs.com.au/nitv/explainer/native-title-what-does-it-mean-and-why-do-we-have-it

6. Continuing Shift in Perspectives

The continuing shift in perspectives on Native Title has meant that more people are accessing and asserting their right to Native title, as well as returning or reconnecting to country in a way that they had not been able to do before legislation was enacted.

There also has been a change in mainstream Australia about Indigenous people in this country. This is particularly apparent as it relates to culture and Indigenous people’s access and expression of culture. Non-Indigenous Australians are uniting with Aboriginal people to assist them in regaining their culture and rights. Government policies and programs are developing, which ideally, will reflect this shift.

Indigenous education is now being offered through courses in schools, colleges and universities in order for people to understand Australia’s First People. This is an invitation to engage in more purposeful and meaningful ways, which benefit Indigenous people, their communities and country.

Today policies move and shift with government, however, Indigenous people must continue to assert their right to land and social justice.

7. Protection and Assimilation

The 1787 Draft Instructions to the first governor of the colony were that the lives and livelihoods of the natives were to be protected. This was reinforced by recommendations of the British Parliamentary Select Committee on Aboriginal Tribes (British Settlements) made to the (British) House of Commons in 1837.

However, as government Protectors were appointed and protection laws passed, their role quickly changed from protection to control of the lives of Aboriginal people.

The protection laws were largely repealed by the 1970s, but the legacy of these laws remains

Protection was a term used by Colonial governments as set out in their own Parliamentary charter of terms, however, what happened away from London and the control of the British parliament was often far from what was prescribed, with massacres being reported and little or nothing done to arrest the situation. Eventually as the early colony began to assert independence from the ‘Motherland’, the demands on access to land increased. ‘Settlers’ and freed convicts were granted greater access and ownership of Aboriginal lands. The law was in the favour of the settlers and freed convicts. As these laws developed more and more control was asserted over the lives of Aboriginal peoples.

It was under the misdirected veil of ‘improving” and “civilising” as well as ‘Christianising’ Aboriginal people., which saw Aboriginal people working as cheap labour for the settlers.

It can be argued that from the 1930s, the policies around assimilation and the institutionalisation of Aboriginal people, created an indentured ‘slave’ work force, that maximised the use of free Aboriginal labour.

Pause for thought

Two former government policies affecting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were Assimilation and Integration. What is the difference between the two policies and how did they impact upon communities?

7.1. Racism Inherent in these Policies

Since the European invasion until very recently, government policy relating to Aboriginal people has been designed and implemented by non-Aboriginal people. The common justification for most policies for Aboriginal people was that they were ‘for their own good’. There have been policies of protection, assimilation, self-determination and reconciliation. It is now clear that none of these policies have actually made the condition of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples any better than it was prior to the invasion.

When the six Australian colonies became a Federation in 1901, white Australia believed that the Aboriginal people were a dying race and the Constitution made only two references to them. Section 127 excluded Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people from the census (although heads of cattle were counted) and Section 51 (Part 26) gave power over Aboriginal people to the states rather than to the federal government. This was the situation until the referendum of 1967 when an overwhelming majority of Australians voted to include Aboriginal people in the census of their own country. The referendum finally recognised Aboriginal people as citizens in their own land. (Author Anita Heiss)

Racism was institutionalised throughout these policies making the very lives of Aboriginal people harder, with many attempting to escape often with severe repercussions, such as jail and or separations from family and country.

7.2. Interpretations of Protection and Assimilation

Indigenous and non-indigenous interpretations of protection and assimilation was of course very different in many instances, with Aboriginal peoples viewing protection and assimilation, first as a physical prison, and later a policy prison. So whilst Aboriginal peoples were ‘protected’ on reserves or missions many of these felt and were run under prison like conditions. After 1930’s with people moving off missions in to larger regional and urban centres assimilation was still a symbolic prison as they were never really free, and still very much under the control of respective government institutions and policies.

7.3. The Residue of these Policies

The residue in relations between Indigenous and non-indigenous peoples today (as a result of these policies) still lingers, with Aboriginal families still disconnected from families and land. Whilst there has been some movement towards equity, entrenched poverty and disadvantage still have a firm grip. The most obvious examples being poor health and housing and the continuation of poor policy.

The far right seem to delight in the statistics that display entrenched disadvantage and herald this as a badge of honour to assert their supremacy. Thankfully this is a very small part of the population, who dislike everyone but themselves.

The greater Australian population, with all its diversity agrees that more needs to be done to support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, in spite of poor policy.

7.4. Transmission of Language

The impact of depopulation on Aboriginal cultures is clearly evident in the decline in transmission of language, with many losing language as they were forced into western systems and institutions. Many Aboriginal people were punished in school or in workplaces for speaking their original language or ‘tongue’. This is an all too common story of colonised peoples around the world.

With Aboriginal language loss came culture loss. Aboriginal culture is an oral tradition as, language carries culture through stories, and proves meaning to signs and symbols. Whilst many Aboriginal people retained their connection to land and people through memory and oral history, some of the stories and meanings were lost with the disintegration of languages. This in many instances means social and economic loss. Today however, Aboriginal people are rebuilding their economy through the use of traditional names, plants and cultural knowledge. There is support for language revival and the reintroduction of local languages being taught to Aboriginal children in schools. In some schools, non-Indigenous students are learning some aspects of language as well.

Pause for thought

It’s been suggested that with the disintegration of Aboriginal and or Torres Strait Islander language, it has led to social and economic loss. What is meant by social and economic loss in this instance?

8. Government Reserves, Missions and Stations

The government of States and Territories set up a system of reserves, missions and stations which were responsible for tending Indigenous populations. There were differences in the way that each operated and who controlled them.

(Government) Reserves: Areas of land reserved by the Crown for Aboriginal people in the 19th century. Much of this land was later taken from Aboriginal people again. Until the 1970s the remaining reserves were administered and controlled by the government.

Stations: Living areas established by governments for Aboriginal people on which managers and matrons controlled (and 'cared for') Indigenous people. These were controlled by private interest groups such as cattle barons with support and control of the government.

Missions: Areas originally set up and governed by different religious denominations for Aboriginal people to live. Today some people use the term to refer to Aboriginal housing developments. The terms "reserves" and "stations" are used as well (controlled by various churches on behalf of the government)

Missions were set up in the 19th century, usually by clergy, to house, protect, and 'Christianise' local Aboriginal people. Using Christian texts to guide and justify their actions, missionaries encouraged Aboriginal people to move into mission settlements and join small European Christian communities.

Many Aboriginal people disliked the mission system, and started to demand their own land. The colonial government responded by setting up Aboriginal reserves or stations. Often, these had previously been mission settlements. The reserves had their own machinery, and farmed their own crops and livestock.

The three best-known 19th-century missions in NSW were Cumeragunja, Warangesda and Brewarrina. In 1893 these places were taken over by the government and run as stations or reserves. In 1911, at the height of the government's program of reserve lands, there were 115 reserves. Of these, 75 had been created because of Aboriginal demands for land.

The stories of missions and reserves tell of a time when Aboriginal nations had been devastated by disease, pastoral expansion and conflict. Aboriginal people were heavily restricted in their access to land and freedom of movement. Missions and reserves remain important today because of their ongoing use by Aboriginal people, and because of the deep and personal attachments many people still have to missions and reserves.

Source: http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/nswcultureheritage/Missions.html

Information about reserves and missions in Victoria can be found at: https://deadlystory.com/page/culture/history/Creation_of_reserve_system

Today, most missions have vanished but some still exist, if in different forms. Depending on their governance structure, many have been reclaimed by the inhabitants and are now in their control. Some have become towns in their own right. Many are actively working to build their communities, improve the lives of their peoples and deal with the aftermath of what happened to them. One example of this is Cherbourg, Queensland. You can read about their community, history, and current endeavours on their website.

Source: https://aiatsis.gov.au/explore/missions-stations-and-reserves

8.1. Positive and Negative Effects

Very little can be argued about the positive benefits of reserves missions and stations, with the exceptions that fewer Aboriginal people would be vulnerable to slaughter and massacres. The obvious negative effects being the removal of peoples from Traditional Lands, the disconnection from their people and the destruction of their culture.

Watch Series 1, Episode 1 of The First Australians:

You

can watch all seasons and episodes of The First Australians through your free

SBS On Demand subscription

9. The Stolen Generation

The history of the 'Stolen children' varies depending on time and place. Table 7.1 below, shows where and when Indigenous children could lawfully be taken without their parents' consent and without a court order. Non-Indigenous children could also be removed without their parents' consent, but only by a court finding that the child was uncontrollable, neglected or abused.

Table 7.1: State and Territory laws authorising forcible removal of Indigenous children

|

Source: Appendices 1-7, Bringing them home, Report of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families, HREOC, 1997

9.1. The First Removals

By the 1890s, the Aboriginal Protection Board developed a policy of segregation. Armed with growing legal control over the lives of Indigenous people, the Board sought to remove children of 'mixed-descent' from their families. These children were later to be merged into the non-Indigenous population.

This policy was based on the idea that children could be 'socialised as Whites' and that 'Aboriginal blood' could be bred out. The authorities believed that if the number of 'half-castes' was growing in comparison to 'full-bloods', then gradually they would biologically assimilate into European society. This could only be achieved by separating 'full-bloods' from 'half-castes'.

The first homes were built for young Indigenous women, such as the one at Warangesda station built in 1893. Some 300 Indigenous women were removed from their families and housed at this station alone between 1893 and 1909. The Board relied on persuasion such as offering free rail tickets, and threats to remove the children.

In 1909, this legal power was granted. The Aborigines Protection Act 1909 gave the Board power 'to assume full control and custody of the child of any aborigine' if the court found the child to be neglected. It also allowed the Board to send Indigenous children aged between 14 and 18 years to work.

Given the ACT's location in regional NSW and the continuation of NSW administration, there was no real distinction between the ACT and the rest of NSW. The few Indigenous children who lived in the ACT also came under the control of the NSW Protection Board.

Five years later, the Board told all station managers that all 'mixed-descent' boys over 14 years must leave the stations to work. Girls over 14 years either had to work or be sent to the Cootamundra Training Home where they were trained in domestic services.

Even so, it was still difficult to implement the separation policy. For children under 14 years, the Board had to prove to a court that the child was neglected before they could be removed. This process often took a long time; often long enough for the family to leave the reserve or move to Victoria. The Board requested extended powers.

These were granted in 1915. Under these laws, the Board now had total power to separate children from their families without having to prove the child was neglected. In fact, no court hearings were necessary. The manager of an Aboriginal station or a policeman on a reserve or in a town could also order removal. The only way a parent could prevent the removal was to appeal to court.

A number of politicians strongly opposed this new law. The Hon P. McGarry said the laws allowed the Board 'to steal the children away from their parents'. Another referred to the laws as the 'reintroduction of slavery in NSW'.

Source: https://www.australianstogether.org.au/discover/australian-history/early-settlers/

The practices of forcible removal of Aboriginal children have a long history in this country virtually going back to colonisation, with first removal starting as early as 1800s,’with the opening of a school for Aboriginal children at Parramatta called the ‘Native Institution’ in 1814. This did not include the kidnapping that had also taken place. Today it is argued that child removal is at an even greater level than it was at the peak of assimilation (Larissa Behrendt).

A 1934 newspaper clipping showing Indigenous children who have been taken from their families as part of the stolen generations. Photograph: Corbis

In 1995, the Commonwealth Attorney General established a National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from their Families, to be conducted by the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (HREOC). The Inquiry report, Bringing Them Home, was tabled in the Commonwealth Parliament on 26 May 1997.

On 18 June 1997, former NSW Premier the Hon. Bob Carr, issued a formal apology in response to Bringing Them Home. Premier Carr moved that NSW:

‘Apologises unreservedly to the Aboriginal people of Australia for the systematic separation of generations of Aboriginal children from their parents, families and communities’ and ‘acknowledges and regrets Parliament’s role in enacting laws and endorsing policies of successive governments whereby profound grief and loss have been inflicted upon Aboriginal Australians’.

On 13 February 2008, history was made when newly elected Prime Minister Kevin Rudd issued a formal apology to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples on behalf of current and successive Commonwealth Governments:

9.2. Kevin Rudd’s Apology to the Stolen Generation

“We apologise for the laws and policies of successive Parliaments and governments that have inflicted profound grief, suffering and loss on these our fellow Australians. We apologise especially for the removal of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families, their communities and their country. For the pain, suffering and hurt of these Stolen Generations, their descendants and for their families left behind, we say sorry. To the mothers and the fathers, the brothers and the sisters, for the breaking up of families and communities, we say sorry. And for the indignity and degradation thus inflicted on a proud people and a proud culture, we say sorry. We the Parliament of Australia respectfully request that this apology be received in the spirit in which it is offered as part of the healing of the nation.”

Source: http://carersaustralia.com.au

Go to the Supplementary Resources for this Module, for a YouTube Video and an audio file with transcript of The Apology.

9.3. Rationale of the Government of the Time

The rationale of the government of the time was not an innovation. A lot was around expediency and costs. Missions and reserves were expensive to run and they needed other ways to” civilise”, “protect” and to ‘Christianise’ the children and assimilate them into mainstream society. This largely happened through indentured work, in the pastoral industry or working for white families as ‘’domestic servants”. Some would argue that they were slaves, given the conditions forced upon them, with little or no pay and forced labour.

Children of mixed-heritage and those who had fair skin (the children of white men) were often taken away from their Indigenous mothers after birth and given to a white family, most often, as a servant. In this period, the definition of 'Aboriginal' was narrowed so that children who were thought to have more non-Indigenous ancestry than Indigenous, were no longer defined as Indigenous and therefore, did not qualify to live on the reserves. This cleared the path for hundreds of children to be taken away from their families. Although this has been happening since the Aboriginal Protection Board was set up in the 1880’s, the assimilation policy made it easier for government agencies to act.

In 1909 the Aborigines Protection Act (NSW) gives the Aborigines Protection Board power to assume full control and custody of the child of any Aborigine if a court found the child to be neglected under the Neglected Children and Juvenile Offenders Act 1905 (NSW). It was in 1940 that the NSW Protection Board lost its power to remove Indigenous children. The Board was renamed the Aborigines Welfare Board and was finally abolished in 1969.

It should be noted that with the roll back of Aboriginal reserves came new difficulties. The demands for land by a booming population in the post war years, elbowed more indigenous people out from their lands. This led to widespread homeless and poverty, leading to poor and ill health.

9.4. Effects on Kinship Structures

The effects and impact on kinship structures was immense. Often, Indigenous children who were removed were not being able to identify their families and communities when they sought to return. This was largely due to incorrect, poorly kept or non-existent records. Today many people are still searching for family and connection to Country. In effect traditional kinship structures had changed, with people marrying outside their Tribe or marriage lines, and into other groups that were not traditionally associated with. This in many instances saw the end of ‘promised” or arranged marriages.

Over many years, Indigenous peoples have raised concerned about the removal of their children and the impact on their identity and cultures. As stated at the First National Conference on Adoption in 1976:

'Any Aboriginal child growing up in Australian society today will be confronted by racism. His best weapons against entrenched prejudice are a pride in his Aboriginal identity and cultural heritage and a strong support from other members of the Aboriginal community.'

9.5. Stolen Generation and Coping Mechanisms

As adults, many of the Stolen Generation have come to seek out their families, upon learning that they have Indigenous ancestry. They seek to know their families, who they really are and what it means to be Indigenous.

Over many years, Indigenous people have developed strategies to cope with the effects of the Stolen Generation. This includes the establishment of organisations and services, specifically set up for returning Indigenous people to families and country. In NSW some of these projects and services include:

· Brewarrina Central School and Bourke High School

· Cootamundra Girls Corporation

· Link-Up NSW Aboriginal Corporation

· Winangali Marumali, Taree

· Kinchela Boys Home Aboriginal Corporation

Strategies developed by these services and programs include:

· education around the stolen generation

· restoration (that is taking people back to country and reuniting families)

· reuniting people who were in the homes

· art therapy programs

· healing camps.

There are many other groups and individuals around the State and the country who work to unite Indigenous people in their everyday life. Some of this important work is done by volunteers, helping to support people, additional to the work of corporations or official services.

9.6. Reuniting Families

There are various methods used to reunite family, to assist in the journey to reunification and healing. Methods used to reunite family include:

· records research – State Archives, State Library, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Islander Studies

· working with a specific Indigenous services who can investigate families such as Link-Up Aboriginal Corporation, and local Aboriginal Medical Services

· becoming involved in local Indigenous organisations and services that may be able to support the journey

· providing important services such as health and mental health support.

People should keep in mind that there are trained professionals who can assist so that people should know they are not alone or without help in this journey.

9.7. The Stolen Generation - Rights and Responsibilities

The rights and responsibilities of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in relation to the Stolen Generations include educating oneself on the history and impact of removals. Please also be conscious of your language and how you address this matter. People are sensitive to how they are referred to, often being dismissed as ‘they have not grown up with an Aboriginal experience or not being Aboriginal enough’.

People have been removed from their Aboriginal families and this does not mean that they are not Aboriginal any more, even if they cannot find their families. The point of working to support Stolen Generations is to heal and to help in reunification and there are many different experiences of this.

Rights:

· to be able to know about history

· to access services and programs to assist

· to be part of the Indigenous community

· to be supported be other Aboriginal people rather than having to justify their Aboriginality

Responsibilities:

· to be educated about the Stolen Generations

· to respectful to people and the subject

· to be supportive and informed

There are many things that people can do collectively, and this includes being more informed about the history and the issues around this matter.

9.8. Statistics

Comparative statistical data shows life expecancy for Indigenous people as taken direcelty from key sources, such as Health Information and the Australian Bureau of Statistics; Department of Prime Minster and Cabinet and The National Centre for Biotechnology, set out the following tables and graphs and comparative notes.

|

Key areas - National |

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander |

Non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander |

|

life expectancy of men |

69.1 |

79.7 |

|

life expectancy of women |

73.7 |

83.1 |

|

infant mortality rates (Male & female/ 1000 births) |

5.8 & 7.1/ 1000 |

3.1 & 3.5/ 1000 |

|

percentage of home ownership |

37.8 |

69.5 |

|

rates of hospitalisation |

950 |

393 |

b. Statistics for NSW and one other State/ Territory or region (as identified)

|

Key areas |

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander |

Non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander |

|

life expectancy of men - NSW |

70.5 |

79.8 |

|

life expectancy of men - NT |

63.4 |

79.7 |

|

life expectancy of women - NSW |

74.6 |

83.1 |

|

life expectancy of women - NT |

68.7 |

83.1 |

|

infant mortality rates (Male & female/1000 births) NSW |

5.6 – 3.8 |

3.6 – 3.2 |

|

infant mortality rates (Male & female/1000 births) WA |

6.3 – 4.8 |

2.1 – 1.9 |

|

Percentage of home ownership - NSW |

37.8 |

69.5 |

|

Percentage of home ownership - Vic |

42.3 |

74.1 |

|

Rates of hospitalisation - NSW |

587 |

361 |

|

Rates of hospitalisation - WA |

1,650 |

386 |

9.9. Housing

Results from the 2018–19 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey (Health Survey) showed that Indigenous Australians were less likely to live in a home owned by a member of the household and were more likely to rent social housing when compared with non-Indigenous Australians.

In 2018–19, 31% (151,560) of Indigenous adults lived in households that were owned or being purchased by a household member (referred to as home owners), 34% rented through social housing (i.e., state or territory housing authority or community housing), and another 33% rented privately through a real estate agent or other arrangements. For non-Indigenous adults, 68% were home owners, 24% rented through a real estate agent or other arrangements, and 3% rented through social housing.

The proportion of Indigenous adults who were home owners increased from 2002 to 2018–19, from 27% to31%. For the same period, the proportion of Indigenous Australians who rented privately or through other arrangements increased from 24% in 2002 to 33% in 2018–19. Indigenous adults renting through social housing providers decreased from 45% to 34% between 2002 and 2018–19.

In 2018–19, Indigenous Australians were 3.7 times as likely to be living in overcrowded conditions as non-Indigenous Australians. Eighteen per cent (145,340) of Indigenous Australians were living in housing considered overcrowded, compared with 5% of non-Indigenous Australians. The 2018–19 rate represented a decline in overcrowding since 2004–05, when almost 27% of Indigenous Australians lived in overcrowded households. This reduction in overcrowding also represented a narrowing in the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians (from a gap of 22 percentage points to 13 percentage points)

The 2016 Census found that Indigenous Australians accounted for one-fifth of the homeless population nationally (20% or 23,440 people); that is, among people whose dwelling is considered inadequate, they have no tenure or their initial tenure is short and not extendable, and they have no control of and access to space for social relations. The 2016 rate was down from 26% in 2011. The 2016 Census found that of the total Indigenous population (649,000) 3.6% or 23,440 were homeless, a rate of 361 per 10,000. This decreased from4.9% (26,700) or 487 per 10,000 in 2011

Sourced on 22/3/23: https://www.indigenoushpf.gov.au/measures/2-01-housing

9.10. Health

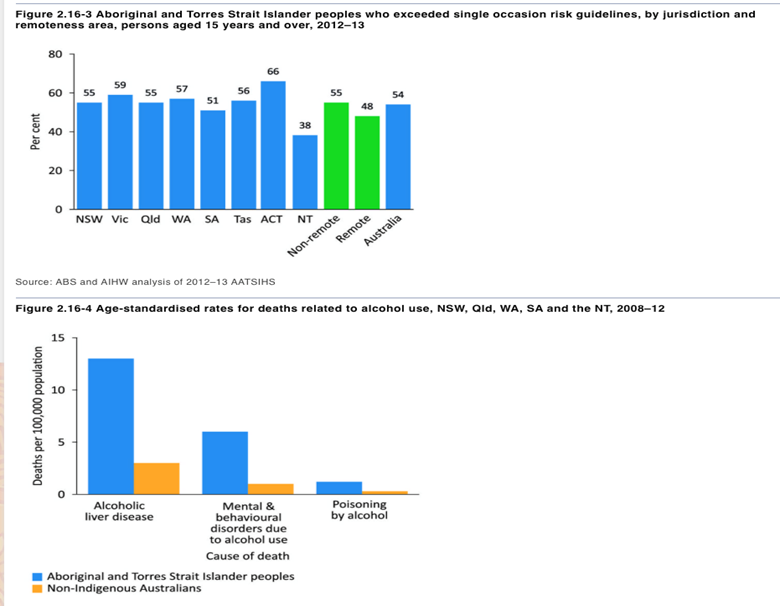

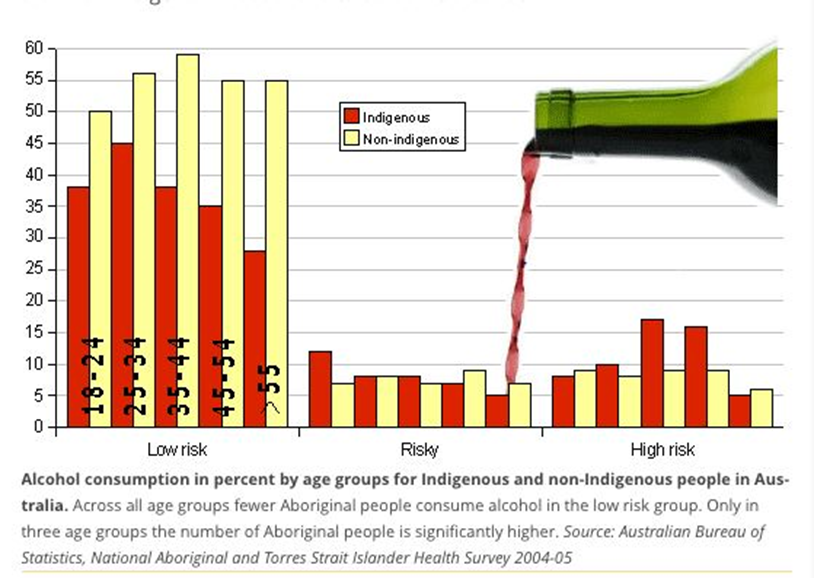

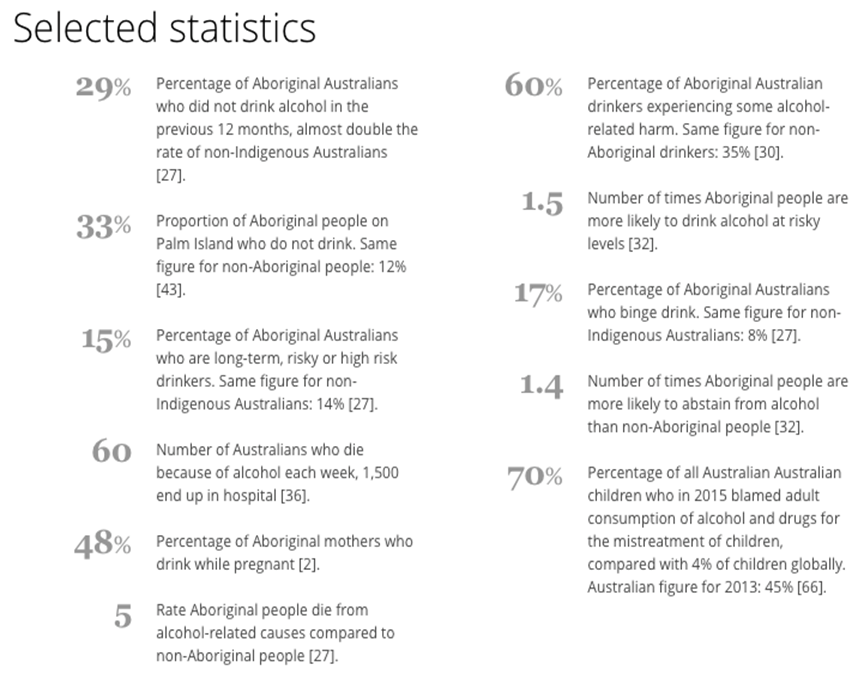

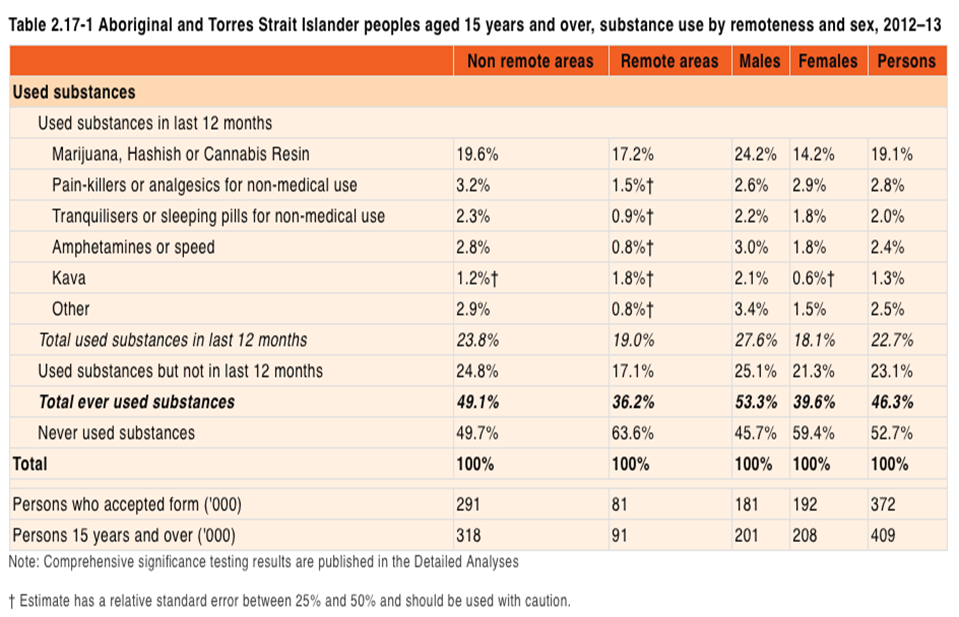

The following five samples of statistical information (graphs and figures) compare Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander AOD usage and related health in Australia.

www.nationaldrugstrategy.gov.au

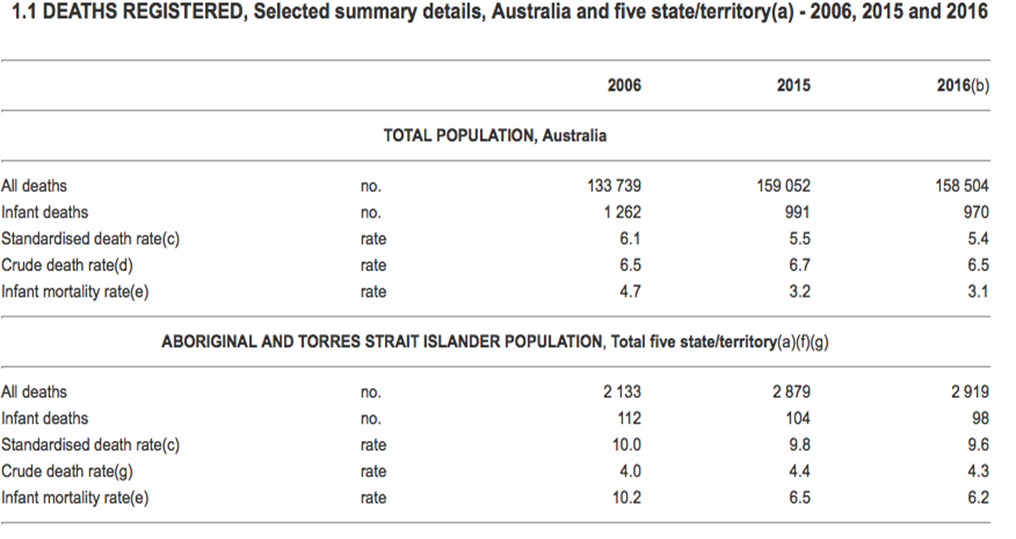

9.11. Mortality rates

* Population figures supplied by the Australian Bureau

of Statistics

Infant Mortality and Life Expectancy

Between 2014-2016, Indigenous children aged 0-4 were more than twice as likely to die than non-Indigenous children. In the Northern Territory, Indigenous infant mortality was 4 times higher than the national rate. [2]

From birth, Indigenous Australians have a lower life expectancy than non-Indigenous Australians:

Non-Indigenous girls born in 2010-2012 in Australia can expect to live a decade longer than Indigenous girls born the same year (84.3 years and 73.7 years respectively).

The gap for men is even larger, with a 69.1-year life expectancy for Indigenous men and 79.9 years for non-Indigenous men. [3]

Indigenous women also experience approximately double the level of maternal mortality in 2016. [4]

Physical and Mental Health

There's a strong connection between low life expectancy for Indigenous Australians and poor health.

In 2016, Indigenous children experienced 1.7 times higher levels of malnutrition than non-Indigenous children. [5]

In 2014-15, hospitalisation rates for all chronic diseases (except cancer) were higher for Indigenous Australians than for non-Indigenous Australians (ranging from twice the rate for circulatory disease to 11 times the rate for kidney failure). [6]

Just under half (45%) of Indigenous people aged 15 years and over said they experienced disability in 2014–2015, compared to 18.5% of the whole Australian population in 2012. [7]

Other major concerns include mental health, suicide and self-harm.

In 2015, the Indigenous suicide rate was double that of the general population. Indigenous suicide increased from 5% of total Australian suicide in 1991, to 50% in 2010, despite Indigenous people making up only 3% of the total Australian population. The most drastic increase occurred among young people 10-24 years old, where Indigenous youth suicide rose from 10% in 1991 to 80% in 2010.

33% of Indigenous adults reported high levels of psychological distress in 2014-15, and hospitalisations for self-harm increased by 56% between 2004-05 and 2014-15.

9.12. Life Expectancy

- In 2015–2017, life expectancy at birth was 71.6 years for Indigenous males (8.6 years less than non-Indigenous males) and 75.6 years for Indigenous females (7.8 years less than non-Indigenous females).

- Over the period 2006 to 2018, there was an improvement of almost 10 per cent in Indigenous age‑standardised mortality rates. However, non‑Indigenous mortality rates improved at a similar rate, so the gap has not narrowed.

- Since 2006, there has been an improvement in Indigenous mortality rates from circulatory disease (heart disease, stroke and hypertension). However, this has coincided with an increase in cancer mortality rates, where the gap is widening.

The target to close the life expectancy gap by 2031 is not on track. The life expectancy target is measured using the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) estimates of life expectancy at birth, which are available every five years.1

In 2015–2017, life expectancy at birth was 71.6 years for Indigenous males and 75.6 years for Indigenous females. In comparison, the non-Indigenous life expectancy at birth was 80.2 years for males and 83.4 years for females (Figure 7.1). This is a gap of 8.6 years for males and 7.8 years for females.

Life expectancy is an overarching target, which is dependent not only on health, but the social determinants (such as education, employment status, housing and income). Social determinants are estimated to be responsible for at least 34 per cent of the health gap between Indigenous and non‑Indigenous Australians. Behavioural risk factors, such as smoking, obesity, alcohol use and diet, accounted for around 19 per cent of the gap (AHMAC 2017).

Sourced on 22/3/23: https://ctgreport.niaa.gov.au/life-expectancy

9.13. Child Mortality

- In 2018, the Indigenous child mortality rate was 141 per 100,000—twice the rate for non-Indigenous children (67 per 100,000).

- Since the 2008 target baseline, the Indigenous child mortality rate has improved slightly, by around 7 per cent. However, the mortality rate for non‑Indigenous children has improved at a faster rate and, as a result, the gap has widened.

- Some of the major health risk factors for Indigenous child mortality are improving. There is a need for further research to understand why these improvements have not translated into stronger improvements in Indigenous child mortality rates.

Sourced on 22/3/23: https://ctgreport.niaa.gov.au/child-mortality

9.14. Physical and Mental Health

There's a strong connection between low life expectancy for Indigenous Australians and poor health.

In 2016, Indigenous children experienced 1.7 times higher levels of malnutrition than non-Indigenous children. [5]

In 2014-15, hospitalisation rates for all chronic diseases (except cancer) were higher for Indigenous Australians than for non-Indigenous Australians (ranging from twice the rate for circulatory disease to 11 times the rate for kidney failure). [6]

Just under half (45%) of Indigenous people aged 15 years and over said they experienced disability in 2014–2015, compared to 18.5% of the whole Australian population in 2012. [7]

Other major concerns include mental health, suicide and self-harm.

In 2015, the Indigenous suicide rate was double that of the general population. Indigenous suicide increased from 5% of total Australian suicide in 1991, to 50% in 2010, despite Indigenous people making up only 3% of the total Australian population. The most drastic increase occurred among young people 10-24 years old, where Indigenous youth suicide rose from 10% in 1991 to 80% in 2010.

33% of Indigenous adults reported high levels of psychological distress in 2014-15, and hospitalisations for self-harm increased by 56% between 2004-05 and 2014-15.

9.15. Education and Employment

About 62% of Indigenous students finished year 12 or equivalent in 2014-15, compared to 86% of non-Indigenous Australians. This is an improvement on previous years.

The proportion of 20–64 year olds with or working towards post-school qualifications has also increased (from 26% in 2002 to 42% in 2014-15).

The employment to population rate for Indigenous 15–64 year olds was around 48% in 2014-15, compared to 75% for non-Indigenous Australians.

9.16. Employment

- In 2018, the Indigenous employment rate was around 49 per cent compared to around 75 per cent for non-Indigenous Australians.

- Over the past decade (2008–2018), the employment rate for Indigenous Australians increased slightly (by 0.9 percentage points), while for non‑Indigenous Australians it fell by 0.4 percentage points. As a result, the gap has not changed markedly.

- The Indigenous employment rate varied by remoteness. Major Cities had the highest employment rate at around 59 per cent compared to around 35 per cent in Very Remote areas. The gap in employment outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians was widest in Remote and Very Remote Australia.

Sourced on 22/3/23: https://ctgreport.niaa.gov.au/employment#:~:text=Between%202008%20and%202018%E2%80%9319,at%20around%2075%20per%20cent.

9.17. Early Childhood Education

- In 2018, 86.4 per cent of Indigenous four year‑olds were enrolled in early childhood education compared with 91.3 per cent of non‑Indigenous children.

- Between 2016 and 2018, the proportion of Indigenous children enrolled in early childhood education increased by almost 10 percentage points. There was a slight decline of less than 1 percentage point for non-Indigenous children.

- The attendance rate for Indigenous children was highest in Inner Regional areas (96.6 per cent), almost 17 percentage points higher than the lowest attendance rate in Very Remote areas (79.7 per cent).

Sourced on 22/3/23: https://ctgreport.niaa.gov.au/early-childhood-education

9.18. School Attendance

- The majority of Indigenous students attended school for an average of just over 4 days a week in 2019. These students largely lived in Major Cities and regional areas.

- School attendance rates for Indigenous students have not improved over the past five years. Attendance rates for Indigenous students remain lower than for non‑Indigenous students (around 82 per cent compared to 92 per cent in 2019).

- Gaps in attendance are evident for Indigenous children as a group from the first year of schooling. The attendance gap widens during secondary school. In 2019, the attendance rate for Indigenous primary school students was 85 per cent—a gap of around 9 percentage points. By Year 10, Indigenous students attend school 72 per cent of the time on average—a gap of around 17 percentage points.

Sourced on 22/3/23: https://ctgreport.niaa.gov.au/school-attendance

9.19. Literacy and Numeracy

- At the national level, the share of Indigenous students at or above national minimum standards in reading and numeracy has improved over the past decade to 2018. The gap has narrowed across all year levels by between 3 and 11 percentage points.

- Despite these improvements, in 2018 about one in four Indigenous students in Years 5, 7 and 9, and one in five in Year 3, remained below national minimum standards in reading. Between 17 to 19 per cent of Indigenous students were below the national minimum standards in numeracy.

- Looking at students exceeding national minimum standards provides a better understanding of how well Indigenous children are placed to successfully transition to further study or work. Between 2008 and 2018, for example, the share of Year 3 students exceeding the national minimum standard in reading increased by around 20 percentage points.

Sourced on 22/3/23: https://ctgreport.niaa.gov.au/literacy-and-numeracy

9.20. Year 12 Attainment

- In 2018–19, around 66 per cent of Indigenous Australians aged 20–24 years had attained Year 12 or equivalent.

- Between 2008 and 2018–19, the proportion of Indigenous Australians aged 20–24 years attaining Year 12 or equivalent increased by around 21 percentage points. The gap has narrowed by around 15 percentage points, as non-Indigenous attainment rates have improved at a slower pace.

- The biggest improvement in Year 12 attainment rates was in Major Cities, where the gap narrowed by around 20 percentage points—from 26 percentage points in 2012–13 to 6 percentage points in 2018–19.

Over the past decade, the Year 12 attainment rate for Indigenous Australians increased by around 21 percentage points, from around 45 per cent in 2008 to 66 per cent in 2018–19. The proportion of non-Indigenous students attaining Year 12 or equivalent also increased, but by a smaller amount (around 5 percentage points). As such, the gap has narrowed by 15 percentage points—from around 40 percentage points in 2008 to 25 percentage points in 2018–19 .

Sourced on 22/3/23: https://ctgreport.niaa.gov.au/year-12-attainment

9.21. Family and Community Wellbeing

Median weekly income for Indigenous Australians was $542 in 2014-15 compared with $852 for non-Indigenous Australians.

Around 20% of Indigenous Australians lived in overcrowded households in 2014-15. In very remote areas the overcrowding was almost 40%.

Rates of family and community violence in 2014-15 were around 22% for Indigenous people.

Indigenous children were almost 10 times more likely to be placed in out of home care than non-Indigenous children in 2015-16.

9.22. Incarceration

In September 2017, Indigenous prisoners represented 27% of the total full-time adult prisoner population, whilst accounting for approximately 2% of the total Australian population aged 18 years and over. The adult imprisonment rate increased 77% between 2000 and 2015.

The detention rate for Indigenous children aged 10-17 years was 26 times the rate for non-Indigenous youth in 2016.

In 2008, almost half of Indigenous males (48%) and 21% of females aged 15 years or over had been formally charged by police over their lifetime.

9.23. Interpreting Statistical Indicators

Statistics show clear disparity between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and Non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians showing disadvantage in all areas.

Some improvements have been made in recent years but these improvements are very minor.

The level of disadvantage of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples compared to non-Indigenous peoples shows a consistently wide gap between the two groups. This includes entrenched poverty and associated disadvantage.

9.24. Comparisons -Indigenous and Non-Inidgenous Disadvantage

An analysis of these statistics has shown a small closing of the gap in access to education, however, poverty remains entrenched even with the introcution of major policy measures and initiatives such as Closing the Gap and the Indigenous Procurement Policy (IPP).

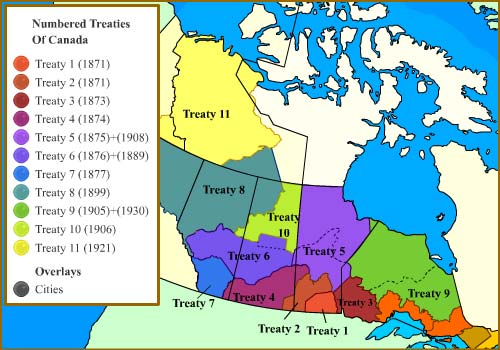

Comparisons with Other Colonised Nations

There are many similarities and differences between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and Indigenous peoples in other colonised nations’ – history, land rights and culture. Here we will look at other nations with similar histories and systems of government such as New Zealand and Canada.

In the instance of New Zealand and Canada they both have treaties, which Australia does not have. In New Zealand indigenous peoples have mandated representation in parliament as well as access to fishing and land rights. Canada also has a Treaty however, this varies with each Territory and Treaty. They do not have a mandated number for representation.

The common thread amongst the three countries (Australia, New Zealand and Canada) is the cultural aspects such as, that traditional customs and rituals, language(s), diet, spirituality, social structure, government or political structure are based on access to land and practice of culture. This is directly impacted by the duration of colonisation. Some examples of common threads include:

· spiritual belief and practice

· laws, social hierarchy, and political structure

· policies imposed by the colonising nation

· indigenous resistance to colonisation

· loss of land, culture, language, etc.

· disparity and disadvantage between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations

· substance misuse

· government apology for past injustices

· ratification of the IDHR or other Human Rights conventions

In all three countries, the Indigenous populations have had to cope with restrictions which inhibited their traditional way of life. All have fought for land rights, regardless of Treaties because in many instances the treaty did not comprehensively address or compensate for the loss of land and culture.

Indigenous people in Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United States of America are worse off by almost any socio-economic indicator than their non-indigenous compatriots. The degree of improvement in the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous disadvantage is slow with entrenched poverty and conditions arising from dispossession and limited access to land, education and markets.

Constitutional recognition in all instances is limited, with countries raising this matter year after year at the United Nations as well as other forums.

Rights to resources is also limited, with many not duly compensated for mining or mineral rights.

Examples of equity gained by Indigenous peoples in other colonised nations is also limited and this varies from country to country. Most often there is very little or limited recognition of their rights, land or culture. There is also limited support for specific indigenous health or education programs.

10. Indigenous Resistance

It is important to emphasise, as Behrendt does, that: “Although the colonists eventually prevailed, Aboriginal people around Australia resisted incursions onto the land, often tenaciously, with violent and tragic outcomes.” [7]

Indigenous Australians didn’t passively accept the invasion of their land, they resisted vigorously, and sometimes violently. It was not only their physical survival that was threatened; their cultural and spiritual survival was also at stake, as sacred sites were desecrated and connection to Country disrupted. In response, they sometimes employed guerrilla tactics, including raiding farms, killing stock, burning buildings, and even killing settlers.

Pemulwuy was an Aboriginal warrior from the Bidjigal clan of the Dharug nation, and a leader of the resistance movement to the south and west of Sydney Cove. These conflicts became known as the Hawkesbury and Nepean wars.

Pemulwuy and his son, Tedbury, led raids on cattle stations, killing livestock and burning crops and buildings. The purpose of these raids was sometimes to obtain food, however they were often in retaliation for atrocities committed against Indigenous people, particularly the women. In response, Governor King ordered the shooting on site of any Aboriginal person in the Parramatta region, and a reward was announced for Pemulwuy’s death or capture.

Pemulwuy survived two bullet wounds, but was eventually killed in June 1802 after being shot by two settlers. He was decapitated, and his head was shipped to England. His son, Tedbury, continued the resistance. [8]

Windradyne was another significant leader of the Aboriginal resistance to white colonisation in the Bathurst region of New South Wales, where several violent clashes between Aboriginal people and white settlers prompted Governor Brisbane to place the district under martial law in August 1824. A reward of 500 acres was offered for Wyndradyne’s capture due to his involvement in incidents resulting in the death of several white settlers. However, Wyndradyne avoided capture, and was formally pardoned when he appeared at the Governor’s annual feast in an apparent move to negotiate. He died on the 21st March 1829 due to wounds suffered during a tribal fight. [9]

Yagan was a Noongar (or Nyoongar) warrior, and led the Aboriginal resistance in the Perth region, Western Australia, until colonists killed him in 1833. His head was severed, preserved, and sent to England. The conflict in the area continued after Yagan’s death; in 1834, Governor Stirling led an attack known as the Battle of Pinjarra. Unofficial reports hold that a whole clan of Aboriginal people was extinguished.

In 1997, Yagan’s skull was finally returned to the Noongar people. [10]

In some areas, such as Arnhem Land, Aboriginal resistance succeeded in stalling the spread of the frontier. However, as Behrendt notes, “in the end, the squatters had the law and the firepower on their side.” [11] Indigenous people, their populations severely depleted by disease, dispossession and violence, drifted to the town fringes, cattle stations and Christian missions.

Despite this outcome, Indigenous people continue to demonstrate incredible resilience today as they fight for recognition of their dispossession and ongoing rights to land.

10.1. ‘Official’ Australian History and the Resistance Wars

‘Official’ Australian history (i.e. history as it was presented prior to truth telling) and the resistance wars is at odds with stories from Indigenous people and Indigenous historians. Australian official history inferring that there was a peaceful settlement and that Indigenous people were treated well or justifying treatment, policies and laws.

More and more we see historians, academics, activists and writers refuting official history versions of Indigenous Australia. These ‘new’ histories are based on researched fact, narratives from Indigenous people themselves and revisiting early accounts with new information.

10.2. Verifying Information in Historical Accounts

Verifying information is historical accounts is very important and can be done by cross referencing a variety of sources, included published articles, documents, and archaeological evidence. This can be done on-line or visiting libraries’, particularly State Library and State Archives. Tranby also has a Library of significance and importance that hold artefacts, videos, and recoded stories. This is also called source criticism.

Source criticism (or information evaluation) is the process of evaluating the qualities of an information source, such as its validity, reliability, and relevance to the subject under investigation.

Gilbert J Garraghan divides source criticism into six inquiries:

- When was the source, written or unwritten, produced (date)?

- Where was it produced (localization)?

- By whom was it produced (authorship)?

- From what pre-existing material was it produced (analysis)?

- In what original form was it produced (integrity)?

- What is the evidential value of its contents (credibility)?

The first four are known as higher criticism; the fifth, lower criticism; and, together, external criticism. The sixth and final inquiry about a source is called internal criticism. Together, this inquiry is known as source criticism.

Please note that when researching Indigenous people and history, the researcher must be mindful of deceased persons. Indigenous people ask that people be mindful and respectful of the deceased person as well as material that may be researched.

10.3. Language Survival and Maintenance

The survival and maintenance of Aboriginal languages in Australia depends on their transmission from generation to generation.

In Australia in the late 18th century, there were more than 250 distinct Aboriginal social groupings and a similar number of languages within these. At the start of the 21st century, fewer than 150 Aboriginal languages remain in daily use, and all except only 13, which are still being transmitted to children, are highly endangered.

There are now language survival and maintenance programs in place for instance, Wiradjiri is being taught in some schools in NSW, as well as local language education programs happening on other areas.

11. Aboriginal Rights and Civil Rights

Boxer Jack Johnson, who claimed victory in Sydney for the world title in 1908, was Inspired and supported by American civil rights activists. This in turn inspired early Aboriginal activists such as William Ferguson and Jack Maynard. This saw a growing civil rights movement in Australia, especially after the WWI when more and more Aboriginal people came off the land and into cities. Encouraged by their inclusion in the war and buoyed by the chance to make a better life for themselves and their families.

This movement gained momentum, cumulating in the late 1950s where Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal activists came together to look at ways they could support better conditions for Indigenous Australians and repeal laws that restricted and deprived Indigenous Australians of their civil rights.

'Fights for Civil Rights' is an account of seven keys civil rights campaigns and the activists and organisations that participated in them. It begins with the Warburton Ranges campaign in the 1950s. The film about conditions of Aboriginal people in the Warburton Ranges was used as a rallying point for civil rights activists Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal and a call for justice and action. Working its way through to the push for 1967 Referendum, which was an accumulation of a ten-year campaign by civil rights activists to make this happen.

Twenty-six people attended this meeting, which formed the Federal Council for Aboriginal Advancement, including the three Aboriginal delegates and Bill Onus, an Aboriginal observer, representing the Australian Aborigines' League.

Aboriginal delegates Jeff Barnes, Doug Nicholls and Bert Groves, The Advertiser, Adelaide, 17 February 1958

11.1. Land Rights and Cultural Survival

Native title is not the same as land rights. Land rights are granted through legislation, which grants the land title of the land to a community, to be passed on to future generations of Aboriginal people. Native title is the recognition of rights to access, based on the traditional laws and customs that existed before colonial occupation. Unlike land rights, native title rights are not granted by government (granted by the federal; court) so cannot be withheld or withdrawn by Parliament or the Crown, although native title can be extinguished by an Act of Parliament.

A land rights grant may cover traditional land, an Aboriginal reserve, an Aboriginal mission or cemetery, Crown land or a national park. Native title only covers land on which a traditional relationship continues to exist.

Understand that Native title cannot be recognised on land, which is fully owned by someone else. It can only be recognised in areas like vacant land, owned by the government (this is called 'Crown land').

Land Rights are important as this speaks to cultural, social and civil rights and people’s direct links to country and culture. It is therefore, vitally important to cultural survival as it sits at the heart of people maintaining land - maintaining culture.

11.2. Treaty

Indigenous people have been calling to the government for a treaty with Indigenous Australians, which has been the subject of political debate. In considering this we can look at some options for what the agreement could include and how it would be created. New Zealand and Canada are both often referred to in the ongoing debate as two examples where British settlers signed a legally binding treaty with indigenous populations.

11.3. New Zealand

Photo: Artist Unknown 1856 New Zealand Treaty

Ref: PUBL-0151-2-014 Shows Veili, a white-haired Maori chief, placing a coin in a collection basket on a table, while Rev William Puckey and Rev Joseph Matthews look on. Veili holds a small child by the hand, and chief Pana-kareao and his wife stand in the right foreground, while a large group of Maori talk together in the background. The mission station at Kaitaia is on a slope in the background.

The Treaty of Waitangi was signed in 1840 and is New Zealand's founding document, instead of a constitution. Its signing is celebrated every year as the national holiday, in a similar way to Australia Day being celebrated here. The Treaty is often referred to in legislation and trade deals.

New Zealand was the only country out of the 12 Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) signatories to have an explicit carve-out for its treaty with the indigenous population, which meant the TPP could never override the Treaty of Waitangi.

The document was presented to 500 Maori chiefs by the first British resident in New Zealand, James Busby, but not every chief signed. Eighteen years after the treaty was signed, the government had the first of many battles with Maori tribes who did not recognise their authority.

There are two versions of the treaty, the English version gives more power to the British settlers than the version written in Maori. In article one of the British version, Queen Victoria has "sovereignty" over the land but the Maori version says she has "governance." Disputes under the treaty are still being settled today by the Waitangi Tribunal.

11.4. Canada

Canada - The Numbered Treaties (or Post-Confederation Treaties) are a series of eleven treaties signed between the Aboriginal peoples in Canada (or First Nations) and the reigning monarch of Canada (Victoria, Edward VII or George V) from 1871 to 1921.

Britain and the Canadian Governments have entered into many treaties with Canada's Aboriginal people. The first was in 1701, but they continued to sign treaties after the constitution formed the foundation of the Canadian government.

Earlier treaties focused on maintaining the peace with the indigenous peoples. Later treaties focused on trading agricultural goods and land rights. Twenty-six treaties have been signed since 1973 to settle Indigenous rights to land, water and resources. Some of the agreements also allow aboriginal people to self-govern. The Government is still negotiating about 100 land-claim and self-government treaties.

Treaties, though sometimes complex and out-dated, still speak of rights and land. There is a preference by Indigenous people in Australia for a Treaty and talks have been in place for many years since the early records of Aboriginal activism.

Please go to the Supplementary Resources, on Moodle for additional information in articles, videos, audio and website links, related to the topics in Block 2.

12. References

1. Reynolds, H. 2013, Forgotten War, NewSouth Publishing, Sydney, pg.16

2. Reynolds, H. 2013, Forgotten War, NewSouth Publishing, Sydney, pg.30

3. Reynolds, H. 2013, Forgotten War, NewSouth Publishing, Sydney, pg.324. Firth, R. 1932 in Reynolds, H. 2013, Forgotten War, NewSouth Publishing, Sydney, pg. 27

5. Behrendt, L. 2012, Indigenous Australia for Dummies, Wiley Publishing Australia PTY LTD, Milton, Australia, pg.251

6. Behrendt, L. 2012, Indigenous Australia for Dummies, Wiley Publishing Australia PTY LTD, Milton, Australia, pg.251

7. Behrendt, L. 2012, Indigenous Australia for Dummies, Wiley Publishing Australia PTY LTD, Milton, Australia, pg.202

8. Behrendt, L. 2012, Indigenous Australia for Dummies, Wiley Publishing Australia PTY LTD, Milton, Australia, pg.242-243

9. Behrendt, L. 2012, Indigenous Australia for Dummies, Wiley Publishing Australia PTY LTD, Milton, Australia, pg.268-269

10. Behrendt, L. 2012, Indigenous Australia for Dummies, Wiley Publishing Australia PTY LTD, Milton, Australia, pg.283

11. Behrendt, L. 2012, Indigenous Australia for Dummies, Wiley Publishing Australia PTY LTD, Milton, Australia, pg.313

https://australianmuseum.net.au/glossary-indigenous-australia-terms

https://www.sbs.com.au/nitv/explainer/native-title-what-does-it-mean-and-why-do-we-have-it

http://www.sydneybarani.com.au/sites/government-policy-in-relation-to-aboriginal-people/

https://australianmuseum.net.au/glossary-indigenous-australia-terms

https://www.australianstogether.org.au/discover/australian-history/early-settlers/

http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/nswcultureheritage/Missions.htm

http://www.healthinfonet.ecu.edu.au/health-facts/summary

https://www.australianstogether.org.au/discover/australian-history/early-settlers/