M5 - Learner Manual

| Site: | Tranby National Indigenous Adult Education & Training |

| Course: | 10861NAT Diploma of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Advocacy 2024 |

| Book: | M5 - Learner Manual |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Thursday, 29 January 2026, 6:09 PM |

Table of contents

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Institutional Settings

- 3. Assess Conflict

- 4. Negotiate Resolution

- 4.1. Use negotiation techniques that maintain positive interaction and divert and minimise aggressive behaviour

- 4.2. Use communication techniques that are effective in ensuring mutual understanding

- 4.3. Ensure negotiation styles take into account social and cultural differences

- 4.4. Confirm mutual agreement to strategies and required outcomes with all relevant stakeholders

- 5. Evaluate Responses

- 5.1. Provide accurate and constructive observations of incidents and their contributing factors when reviewing and debriefing the situation

- 5.2. Provide and maintain records and reports in accordance with organisational requirements

- 5.3. Recognise effects of stress in self and manage using recognised stress management techniques

- 6. Annexure A

- 7. Annexure B Use of Force – NSW Ombudsman Report

- 8. Annexure C Incidents – WA Department of Corrective Services – Policy Directive 41: Reporting of Incidents and additional notification

- 9. Annexure D Incident Reporting – WA Department of Corrective Services – Policy Directive 41: Reporting of Incidents and additional notification

- 10. Annexure E Stress Management – Queensland Corrective Services Procedure

- 11. Prepare for mediation

- 12. Conduct mediation interview

- 13. Document outcomes of mediation interview

- 14. Services and Agencies Relevant to Mediation

1. Introduction

Block 5 includes two units of competency:

- CSCSAS024 Manage conflict through negotiation

- NAT10861008 Provide mediation for clients needing legal assistance

CSCAS024 Manage conflict through negotiation

This unit of competency describes the outcomes required to use communication techniques to manage a conflict situation. It requires the ability to assess conflict situations, accurately receive and relay information, adapt interpersonal styles and techniques to varying social and cultural environments and evaluate responses.

This unit applies to all people working in detention centres, correctional centres or prisons, community corrections offices, justice administration offices and on work sites where detainees, prisoners or offenders are under statutory supervision. Variables will determine different applications of the standards depending on the nature and complexity of security requirements, security ratings and defined work role and responsibilities.

The language used in this unit implies an institutional setting. Adaptation of the language will be necessary to reflect the practices of non-institutional settings and work sites. Customisation should occur through the introduction of specific organisation security equipment, functions and procedures.

NAT10861008 Provide mediation for clients needing legal assistance

This unit describes the performance outcomes, skills and knowledge required to mediate fair and equitable outcomes for Indigenous clients in circumstances of legal disputes.

2. Institutional Settings

There are a number of different institutional settings where conflict situations may arise. It is important to be aware of these different contexts and what laws or rules may apply depending on the work environment a person is in. For the purposes of this unit we are looking at the following institutional settings:-

1. Detention Centres

2. Correctional Centres or Prisons

3. Judicial Administration Offices

4. Work sites where detainees, prisoners or offenders are under Statutory Supervision

In each of these situations different laws and policies will dictate how employees need to conduct themselves, what their responsibilities are and how conflict situations should be managed through negotiation.

In each context people work in different jobs as part of the broader institutional setting. For example,

1. Detention Centres: There are custodial officials, office administrators, cleaners and cooks. There are also social workers, health professionals, doctors, psychologists, torture and trauma counsellors who all visit the detention centres. Lawyers and legal representatives can also visit.

2. Correctional Centres or Prisons: There are custodial officials, office administrators, cleaners and cooks. There are also social workers, health professionals, doctors, psychologists, torture and trauma counsellors who all visit the detention centres. Lawyers and legal representatives can also visit.

3. Judicial Administration Offices: This term refers to the different court offices. There are the officers of the court such as a Magistrate or a Judge. There are also administrative staff and Bailiffs. Clients, support staff and lawyers attend these offices.

4. Work sites: This refers to situations where detainees, prisoners or offenders are under Statutory Supervision. For example they may be on ‘work release’ from prison or completing Community Service Hours as part of a court order. Here we have the supervising persons responsible for supervising the person whilst they are working.

In each of these settings conflict situations can and do arise. It is really important that anyone working in these settings has a good understanding of what a conflict situation is and how to deal with it if one arises. It is particularly important to be aware of using negotiation as an effective tool for managing a conflict situation.

Why is this important?

When we are at work it is really important that we understand that conflict situations can arise and ensure we are well equipped to deal with them. Managing conflict is an important part of life.

A. If you are working in a position on one of these institutional settings then you need to be aware of your responsibilities and the different processes for dealing with a conflict situation. For example, a detainee may become aggressive toward you and you will need to take steps to de-escalate the situation.

B. If you work in a legal organisation as a legal clerk or a support worker you may have a client who tells you about a conflict situation that has arisen for them. You will need to know about the policies and processes that exist so you can help your client and assist them in advocating their rights. For example, your client may have a grievance in relation to a policy or procedure. You may need to advocate on their behalf for a review of a decision.

3. Assess Conflict

Consider likely and possible conflict situations to prevent escalation

Assess potential conflict

‘Conflict’ is a disagreement, clash or fight between individuals or groups.

Conflict happens between people every day to some degree. There can be many different causes. You will need to develop skills to recognise potential conflict situations and prevent things from getting out of hand.

In a custodial setting where there are inherent power imbalances there is strong possibility that conflict situations will arise regularly. People who have been deprived of their liberty may have a range of issues that can arise.

Conflict can arise due to a number of different types of situations. For example:-

Ø Communication may break down between parties

Ø A person may have a cognitive or mental health issue that makes processing information difficult

Ø Cultural considerations may be ignored

Ø Jumping to conclusion or prejudging a situation / person

Ø A special event or date may be a trigger for distress and anger

Ø A person may feel hurt or threatened

Ø A person may not follow a lawful direction

Ø A person may commit or attempt to commit an offence or a breach of discipline

Ø A person may self-harm or attempt to self-harm

It is important to be aware of the different situations where conflict can arise. Awareness and sensitivity can assist you to prevent conflict from arising in the first place or with being properly prepared to manage a situation when it arises. By being aware of the different situations where conflict can arise you can turn your mind to exactly which legal requirement applies and what organisational policy you will need to turn to so you can manage the situation.

3.1. Organisational strategies to prevent conflict

Depending on the situation, a range of strategies can be used to help prevent conflict. These include:

Listing preventative measures.

Face-to-face meetings.

Listening and respect.

Develop Code of Conduct and relevant policies and procedures.

Grievance policy and procedure.

Memorandums of understanding.

Culturally appropriate strategies

Training Board members and staff members in conflict management.

Get together with concerned parties to address concerns informally as they arise.

Do not sweep potential conflict under the carpet.

Note disagreements between parties that may have the potential to become conflicts.

Take individuals aside for a private discussion about their attitude or behaviour if necessary.

Establish clear policies on expected behaviours.

In meetings, deal with problem issues later in the meeting so it does not interfere with other business.

Face-to-face

meetings:

Set up a face-to-face meeting between individuals or parties involved in the conflict to discuss the problem.

Encourage calm discussion.

Carry out discussions in a non-confrontational way.

Avoid always having to be ‘right’. You may have to give a little in the best interests of the organisation and community.

Listening and respect

Listen to all people’s points of view:

Keep an open mind.

Show respect, even if you disagree.

Note areas where two parties can agree.

Find positives to build upon in an individual’s position.

Avoid blaming others.

Develop a Code of Conduct/Ethics on expected behaviours within the organisation.

Develop Policies and Procedures to deal with potential conflict situations including a grievance policy

Make sure all Board Members and staff follow the Code of Conduct/Ethics and Policy and Procedures.

Nepotism - develop a policy that deals with conflicts of interest - eg employing immediate family.

Make sure the organisation uses a merit based system for employing staff and ensure that there are no family members on the interview panel.

Memorandums of understanding

If necessary, develop a Memorandum of Understanding between the Board and Management or staff.

This is a legal agreement that clearly sets out the roles and responsibilities of the concerned party (or parties).

It can be necessary if there are misunderstandings about, or abuse of, roles and responsibilities.

Cultural resolution strategies

Provide training in how to resolve conflict in culturally relevant ways.

Make sure all staff know and use culturally appropriate strategies for preventing conflict.

Training Staff

Train staff so they can carry out their roles in the correct manner, following due process.

Train management in recognising, preventing and dealing with conflict.

Ensure staff members understand each other’s roles and responsibilities - can prevent misunderstandings.

By being aware of your own organisational policies and procedures you will be able to identify what process or steps you need to take in a particular situation. It may be that you need to seek assistance from somebody such as your supervisor or manager. In some situations it is important for you to seek advice and get help in order to manage a conflict situation. A sound knowledge of your own organisational policies will help you to do this.

3.2. Identify and evaluate responses to conflict against legal requirements and organisational procedures

In any job you need to be really clear if any legal framework applies to your position and has an impact upon how you need to do your job. Generally, if you work in a legal setting you will need to comply with some legal obligations. For example, issues relating to duty of care and confidentiality are an essential part of any legal practice for both the lawyers and all the support and administrative staff too. Similarly, the laws relating to Workplace Health and Safety are also relevant.

In some jobs there will be an additional legal framework that will shape your duties and responsibilities whilst you are at work. This will impact a range of things including:

peoples rights and responsibilities

general processes and procedures

recording keeping

conflict resolution

evaluation

grievance procedures

wages

For example:-

In NSW there are a number of legislative instruments that impact upon work done in relation to Corrective Services.

Acts

Crimes (Administration of Sentences) Act 1999

Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act 1999

Crimes (Interstate Transfer of Community Based Sentences) Act 2004

Protected Disclosures Act 1994 No 92

Summary Offences Act 1988 No 25

Prisoners (Interstate Transfer) Act 1982 No 104

Parole Orders (Transfer) Act 1983 No 190

International Transfer of Prisoners Act (New South Wales) 1997 No 144

Prisoners (Interstate Transfer) Act 1982 No 104

Ø More legislation can be found at the NSW Parliamentary Counsel's Office website

Regulations

Crimes (Administration of Sentences) Regulation 2008

Prisoners (Interstate Transfers) Regulation 2004

Crimes (Interstate Transfer of Community Based Sentences) Regulation 2004

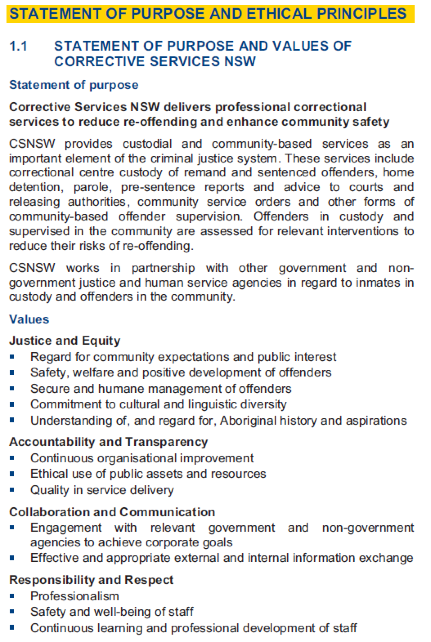

NSW Example: Conduct and Ethics

You will usually find that your organisational policies and procedures will reflect all the relevant laws and rules for your institutional setting. For example see “Annexure A”, extracts from the NSW Corrective Services Guide to Conduct and Ethics, 2010. These extracts illustrate some examples of an organisational policy dealing with topics such as Ethical Principles, Public Duty, Professional Conduct Towards Offenders and Professional Conduct Towards Employees.

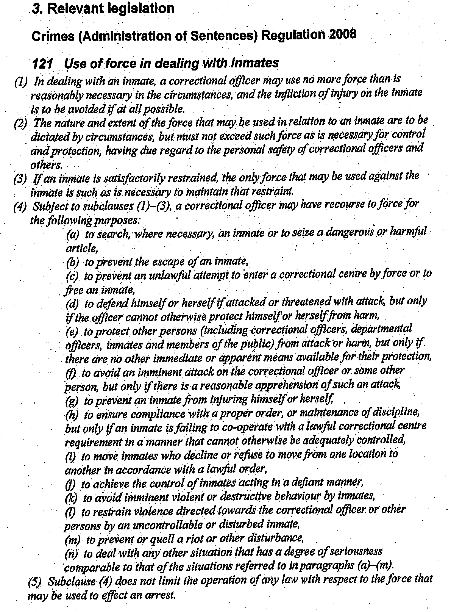

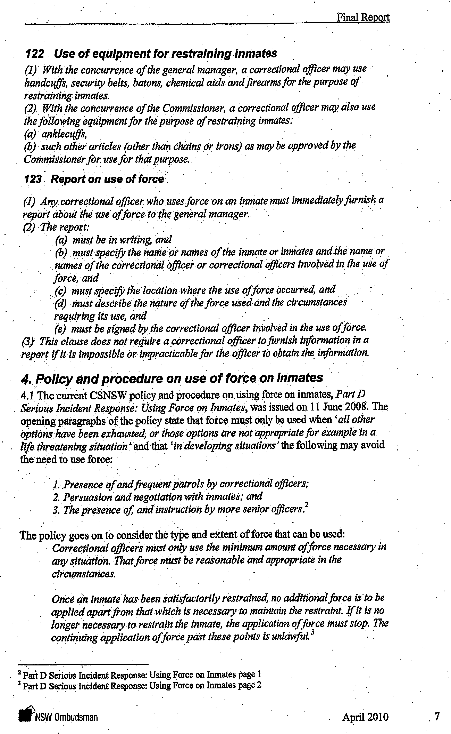

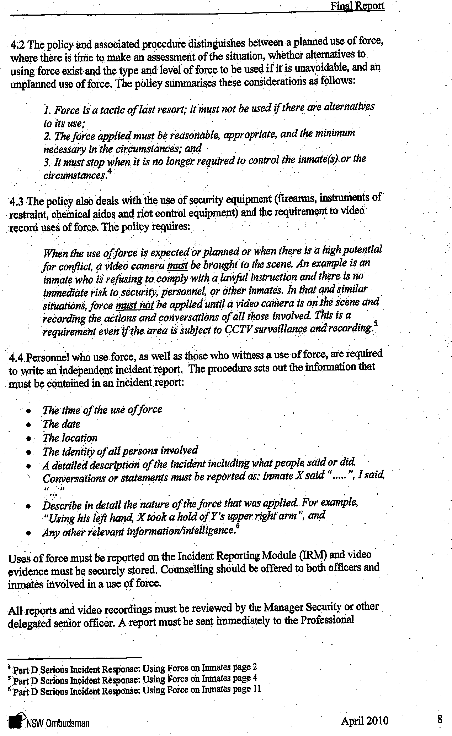

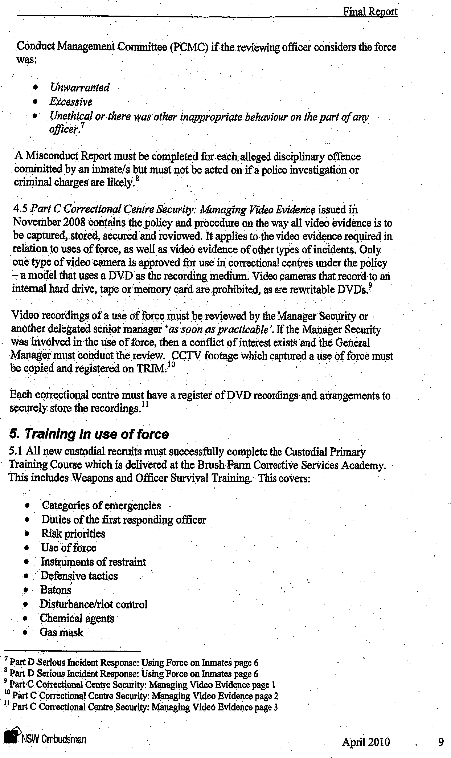

NSW Example: Use of force

In NSW the Crimes (Administration of Sentences) Regulation 2008 (regulations 121. 122 1n2 123) deals with the ‘use of force in dealing with inmates’ in a custodial setting. Corrective Services NSW have developed an organisational policy to deal with these provisions. Specifically, in the Operations Procedures Manual, Part D: Serious Incident Response: Using Force on Inmates, 11 June 2008. Please refer to “Annexure B” to see extracts of this policy from the NSW Ombudsman Report, 14 April 2010. Here we see an example of an organisational policy that sets out the requirements for staff to take in a conflict situation where the ‘use of force’ becomes an issue. You will see reference to the use of force being a ‘tactic of last resort’ and it identifies other options such as persuasion and negotiation as methods of diffusing a conflict situation.

Examples of other jurisdiction’s legislative instruments that impact upon work done in relation to Corrective Services.

Western Australia

Prisons Act 1981

Prisons Regulations 1982

Queensland

Corrective Services Act 2006

Corrective Services Regulations 2006

Each State and Territory has its own legislative framework dealing with corrective services and prisons.

Immigration Detention Centres are governed by Commonwealth legislation including:

Migration Act 1958

Migration Regulations 1994

3.3. Identify situations requiring assistance and support and request assistance promptly

What negotiation and conflict have in common

The obvious common denominator between negotiation and conflict is that they both involve a relationship with at least one other person. Albeit the relationship may only be a short term one.

When you enter into a negotiation or find yourself in conflict with another person, the outcomes you and the other person desire appear to be diametrically opposed. Otherwise there would not be a conflict or need for serious negotiation.

The extent to which you have invested (time, money, emotion, ego, etc.) in the outcome of either situation may make it easier or harder to achieve what you want. It is unlikely to enter into a negotiation, or find yourself in conflict if you do not care about the outcome. In general, you already have an emotional, financial or other investment.

The difference between a conflict situation and entering a negotiation is that the tension levels are already high when in conflict and relationships may have already been damaged.

In either situation, it is common that both parties see themselves as ‘right’, and want to prove their ‘rightness’ to each other. In this sense every negotiation has potential for conflict.

If both parties maintain their position of ‘rightness’, there is little opportunity for resolution or for either party to achieve their desired outcomes. Relationships may be irretrievably damaged and neither party wins.[1]

Prompt resolution

Conflict should be dealt with as promptly as possible. Where possible, situations should be dealt with straight away. In a custodial setting, employees will usually need to act quickly to prevent a situation from escalating.

Dealing with conflict promptly is important for the following reasons:

If people are at risk of being harmed;

If the conflict is interfering with work;

To help get things back to normal quickly;

It prevents the conflict from continuing; and

It can save the organisation time and money.

The safety of staff and detainees is of paramount importance in custodial institutional settings. For this reason effective and efficient conflict negotiation is essential.

[1] Community Builders, NSW http://www.communitybuilders.nsw.gov.au/332_2.html (accessed 4 August 2010)

4. Negotiate Resolution

Use strategies to resolve conflict that comply with organisational policies and procedures.

In a custodial setting, different situations will give rise to the need for negotiation. It may be that there is:

Conflict between two detainees;

Conflict between a custodial officer and a detainee;

An issue around access to services;

An issue around contact or visits with family members;

There may be a mental health situation that needs to be managed;

A person may commit an offence; or

There may be a concern about self-harm.

In each of these situations the use of negotiation can assist in resolving the issue efficiently and effectively, without escalation to something more serious. By communicating with relevant parties you can try to identify a solution that is agreeable and workable for all those involved. Different communication techniques will be more effective at different times. For example, listening, active listening, writing a letter, being assertive, being passive and sitting back. Each situation will call for a different approach. For example:

If an employee is negotiating visits then they will need to speak with welfare officers, family members and corrective services administration.

If an employee is de-escalating a conflict between inmates then they may call on assistance from a colleague and use distraction or diversion as a way to negotiate an initial resolution.

If there is a concern about self-harm the employee will need to seek assistance from health professionals.

There are some situations where an employee may need to use to force if negotiating is unsuccessful

Complaints Resolution Policy

Often you can expect that a complaint may arise about the way that a conflict situation has been handled, in which case it is important to be clear about the organisational ‘Complaints resolution policy’.

Each organisation should have a Complaints Resolution Policy to deal with complaints about the organisation or individual staff. This sets out the procedure for dealing with complaints, whether they are from within or outside the organisation.

The complaint should be registered in a book or database set aside specifically for that purpose. Each complaint should include the following details:

name of person making the complaint

nature of the complaint - as many facts and details as possible, including names, places, dates

date complaint was made

name of person recording the complaint

what action the person was told would be taken

The person recording the complaint should pass the information on to the appropriate person in the organisation.

The person making the complaint should be told what action will be taken to follow up on their complaint, who will be dealing with it (if known) and when they can expect to hear back from the organisation.

Potential conflict can be averted if staff and Board members follow the correct procedure in registering complaints.

The organisation’s Complaints Resolution Policy should have a timeframe for dealing with conflict. For example, less serious conflict may need to be resolved within 3 days and more serious conflict may need to be resolved within 7 days.

Having a set timeframe that is written down for everyone to see has two benefits: it provides a guide for management to follow, and it allows people involved in the conflict to know the situation will be dealt with promptly.

If a complaint about conflict comes to the attention of management, either verbally or through its correspondence, management should deal with it within the set timeframes. Delays can create more conflict and unnecessary stress and tension for everyone.

The Complaints Resolution Policy of the organisation should be followed so that the conflict is dealt with in an open and transparent manner. All parties should be kept informed about who is dealing with the conflict and when they can expect a resolution. All actions must be recorded.

In some cases, it may be inappropriate or difficult for managers to deal with conflict situations themselves. They may need to seek outside help from an independent arbitrator or mediator. This should only be done as a last resort though, when all else has failed to resolve the conflict.

|

arbitrator ~ person brought in to settle a dispute, usually through a formal process (e.g. Arbitration Commission)

mediator ~ similar to an arbitrator, but less formal

|

Resolution strategies

Different conflict resolution strategies may need to be used for different situations. Be realistic about the nature and severity of the conflict and its chances of being resolved.

Strategies should be developed in consultation with the conflicting parties. This can happen in small meetings, community meetings, or Board meetings.

Involved parties should:

Aim for a friendly ‘win-win’ resolution - where there are no losers and no-one goes away feeling angry.

Try to work out a compromise that satisfies all.

Speak ‘one-to-one’ in a casual setting if possible. Get all sides of the story and respect each person’s right to their own point of view.

Remind concerned parties of the organisations Code of Conduct and what is appropriate and respectful behaviour during a disagreement.

Record what each party said happened. Give each party a copy to verify, comment on or change if necessary and sign and date.

Stick to grievance policies and procedures. Make sure everyone on the Board is aware of this.

Observe cultural resolution strategies. Different cultures have different strategies. Make sure people from different cultural backgrounds are aware of the culturally appropriate strategies for your organisation or community.

Draw up a memorandum of understanding between conflicting parties if necessary. This outlines what each party agreed on to resolve the conflict. Make sure it is dated and signed and a copy given to each party.

Defer the subject causing the conflict for later discussion if necessary. This can delay or minimise conflict and allow important tasks to be completed.

Consider what resources the organisation has for dealing with the conflict. Don’t stretch human or financial resources too far. Seek help if needed.

Keep all parties advised of what is being done to deal with the conflict.

Explain the process to people.

Professional advice is sought

If the conflict cannot be dealt with internally, the organisation may need to seek professional outside help. This can include:

legal advice

conflict resolution professional

unions

arbitrator – e.g. Industrial Relations Court

Legal advice

Some conflict situations may require the organisation to seek legal advice to find out their legal position, or the legal position of a staff member.

Legal advice may be required in situations involving:

crime – e.g. stealing, misappropriation of funds

violence

Organisations have a responsibility to protect their staff from being harmed, or from causing harm to others.

Conflict resolution professionals

Sometimes a person with professional skills in resolving conflict may need to be called upon for advice or mediation.

This can be necessary if the conflict situation is beyond the skills of any staff employed within the organisation in which the conflict has arisen. Also, if there is a personal conflict that a staff member cannot discuss with anyone within the organisation, they may need to discuss it in confidence with a professional.

Mediation may be necessary if the conflict has gotten out of hand. It may need someone who is not close to the conflict to get all sides of the story and find a resolution. A mediator can also suggest strategies to prevent any future conflict from arising.

There may be suitable mediators in your community, or they may have to be brought in from outside the community. A mediator should be impartial and not have a professional or personal relationship with any of the parties involved in the conflict.

Unions

Unions represent workers in issues involving pay disputes, workplace conditions and conflicts between employers and employees. Employees need to know that if they belong to a union, they have the right to contact their union representative to help them deal with a conflict situation. The union can advise them of their rights and responsibilities.

Arbitrator

An arbitrator is like a mediator, but usually in a more formal setting, such as the Industrial Relations Court. In extreme conflict situations that cannot be resolved within the organisation itself, it may need to go to an arbitrator. An example of this could be if a manager of an organisation was contracted for a certain period of time, but the Board terminated his or her contract without due cause. The Manager could take the case to the Industrial Relations Court if he or she was not happy with the situation.

Health professionals

Some conflict may require the advice and assistance of a health professional, such as a health worker, doctor, counsellor, psychologist or psychiatrist. These people are trained in dealing with specific aspects of physical or mental health and can help deal with specific problems. For example, if a person in the organisation was displaying abnormal behaviour or aggression, they may need the help of a health professional to find out what is causing it.

Confidentiality Policy

The organisation or department needs to have a confidentiality policy that clearly sets out how to deal with conflict in a way that maintains discretion and confidentiality

A Code of Conduct/Ethics signed by staff lets people know that they are expected to behave in ways that maintain confidentiality and discretion at all times.

Confidentiality and discretion needs to be an across-the-organisation policy. If these policies and procedures are maintained, it will strengthen the effectiveness of the organisation’s operations by letting staff know they can trust their organisation to do the right thing.

4.1. Use negotiation techniques that maintain positive interaction and divert and minimise aggressive behaviour

Maintain integrity

An organisation must find ways to resolve conflict that maintains integrity. This means acting in the best interests of individuals within the organisation and the organisation itself.

If conflict situations are not dealt with appropriately, they have the potential to ruin people’s lives and can destroy organisations. This needs to be avoided at all times by:

dealing with conflict in-house if possible

acting respectfully at all times be fair, honest, open and trustworthy

protecting the rights of individuals

protecting the staff’s, organisation’s and community’s values

maintaining confidentiality

not shaming people - not making conflict public

Deal with conflict in-house

It is far better to deal with conflict within the organisation, where possible.

Conflict affecting the organisation or individuals within the organisation should not be taken into the community, if possible. This can be difficult in small communities especially, but the organisation needs to try to keep personal conflict separate from its professional or business-like activities.

It is important that people are given an opportunity to explain themselves and tell their side of the story before decisions are made. People should not be yelled at or shamed in front of others. Conflict should be discussed in a private way so that people can keep their dignity. An organisation needs to respect the rights of its employees to have information about conflict concerning them kept confidential. People need to know that their concerns will be listened to and addressed, but not talked about outside the organisation.

If conflict within the organisation is discussed in a public way, it can lead to serious consequences for individuals and the organisation. People’s health and safety can be placed at risk and the community (local and wider community) can lose its trust in the organisation.

Protecting individuals from shame

People should be taken aside to calmly discuss conflict issues in private. They should not be shamed by having someone yell at them in front of their fellow staff members or others.

Conflict should never be dealt with in a heated or shaming way.

Disciplining within the organisation

Where possible, any discipline over conflict situations should be done within the organisation. For example, if a normally even-tempered employee blew up one day and had a big fight with another employee, would you (a) call the police, or (b) tell them to go home, cool down and think about their actions before returning to work? Option (b) would be more culturally appropriate and more supportive to the employee.

Non-confrontational approach

An example of a confrontational approach is when a boss screams at an employee

‘What the hell did you do that for?!!’

This puts the other person’s back up immediately and can shame them in front of others.

In a non-confrontational approach, the boss might say,

‘I can see you had a bit of trouble with that job you did.’

This way, the person is not put in a position of feeling shamed, or having to defend themselves. It also gives them a chance to explain what went wrong.

A non-confrontational approach is a more gentle way of dealing with conflict and can prevent conflict from getting out of hand.

4.2. Use communication techniques that are effective in ensuring mutual understanding

Consultative process

A consultative process for dealing with conflict is one where everyone involved in the conflict is brought together to discuss it. Everyone has a part to play in resolving the conflict in a consultative process.

If necessary, Elders or other respected members of the community may also be consulted on the best way of dealing with the conflict situation. This is essential in communities that still practice traditional ways.

In a consultative process, everyone is given a chance to tell their side of the story. This can be done in an informal way, by sitting down with the person and talking with them about what happened.

In a custodial setting there may be organisational training and policies in place that inform employees about how they should set about negotiating with somebody in a particular situation.

Of course employees must always comply with their organisational and legal requirements. It is important to be aware of these requirements. Usually an employee will sign an agreement as part of their employment contract that they will comply with these requirements.

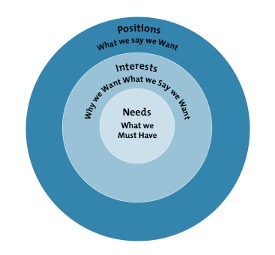

There are some general principles that apply to most negotiating situations and can provide useful insights about how to approach a particular situation. The ‘conflict layer model’ provides some general information about how to understand and approach negotiating.

Clarifying Needs during Conflict Negotiations

|

When you were last involved in a negotiation (however big or small), did you feel that you truly understood the other person's needs? Chances are, you didn't.

During negotiations, it's common for people not to reveal their deepest needs – sometimes, even to themselves. They may feel selfish, foolish, or vulnerable talking about them, so they focus on less important issues instead.

Unfortunately, when this happens, the negotiation may not deliver a long-term solution, because it won't be based on what people really want.

The Conflict Layer Model is a tool that you can use to explore your own true needs in a negotiation situation. Using this technique can assist you to maintain a positive interaction and divert and minimise aggressive behaviour that may be present in a conflict situation.

About the Model

Figure 1 – The Conflict Layer Model

From "Working With Conflict" by S. Fisher et al. Published by Zed Books, 2000. Reproduced with permission.

During negotiations where you don't know or trust the other person, you may hide your needs because you feel embarrassed or vulnerable. Instead, you might take up a stance that's based on how you want to be perceived. This is known as your position.

Behind your position lie your interests. These are the stated reasons that support your position, but they may not represent your true needs.

The model aims to peel away these layers, and to focus on the needs that really matter to you. When you state your needs openly, it will encourage the other party to do the same. Then, once you've both identified and communicated your real needs, you can work to find a solution that meets them.

Note: This model is not suitable for all negotiations. It's more suited to situations in which people feel able to talk freely and openly, and it's less appropriate when people's needs must be hidden, or when people must be seen to "toe a party line."

In this situation, distributive bargaining may be more suitable.

Distributive bargaining is a process of incremental compromises resulting eventually in an agreement with which neither party is entirely happy. Such agreements are normally reached through a process of attrition, after parties become fatigued by the constant conflict and series of meetings and normally one of the parties will capitulate at the end for the sake of reaching an agreement.

The Conflict Layer Model most closely matches a collaboration strategy.

How to Apply the Model

You can use the model to prepare before negotiations begin, as well as to understand other people's needs during the negotiation. Follow the steps below to do your preparation. You can use a similar approach during the negotiation itself.

Step 1: Separate Your Position from Your Interest

Your position is the "want" that you have expressed publicly to the other party. You need to explore this to find your interests – what you want to achieve from this situation.

So, start by writing down what you have said you need, or what you think you want to achieve from this situation.

Next, list the reasons you've given to support your position. These are your interests. (If necessary, use the 5 Whys technique to explore why these issues or solutions are important to you.)

The 5 Whys is a repetitive question-asking technique used to explore the cause and effect relationships underlying a particular problem. The primary goal of the technique is to determine the root cause of a problem. (The "5" in the name derives from an empirical observation on the number of repetitions typically required to resolve the problem.)

Step 2: Identify Your Needs

Once you have identified your interests, your next step is to distil them further to discover your deeper needs. These are the needs you must meet to feel satisfied. Often, they are non-negotiable – you need to meet them for the negotiation to have been a success.

Think carefully about the interests that you have defined. Keep in mind that your interests are often a means to an end – they help you meet your needs. So, what basic or intrinsic needs do these interests help you address?

Then, be completely honest with yourself. Ask yourself if there are other, more self-interested or less easily discussed needs that you need to address as well.

Step 3: Negotiate

Your next step using the model is to state your needs clearly. When you do this, you create an atmosphere of trust that will encourage the other party to be open about their true needs.

Then, negotiate to meet your needs. Where appropriate, use win-win negotiation and integrative negotiation to explore solutions based on shared needs.

Integrative negotiation - to explore solutions, and "trade favours," so that both parties feel satisfied with the outcome.

The model helps you "peel away" the superficial positions that people often adopt at the start of a negotiation, so that you can get to the real substance of what they want. This helps you find a solution that meets the needs of everyone involved.

4.3. Ensure negotiation styles take into account social and cultural differences

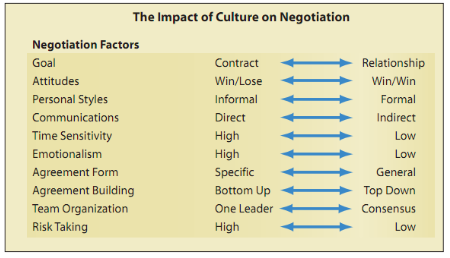

Culture profoundly influences how people think, communicate, and behave. It also affects the kinds of transactions they make and the way they negotiate them. Misunderstandings may arise during the process of negotiation due to a lack of cultural awareness and misunderstandings that may occur unintentionally.

Negotiating styles, like personalities, have a wide range of variation. The ten negotiating traits discussed above can be placed on a spectrum or continuum, as illustrated in the chart below. Its purpose is to identify specific negotiating traits affected by culture and to show the possible variation that each traitor factor may take. With this knowledge, you may be better able to understand the negotiating styles and approaches of counterparts from other cultures. Equally important, it may help you to determine how your own negotiating style appears to those same counterparts.

Source: Salacuse, J.W. (2006). Leading Leaders: How to Manage Smart, Talented, Rich and Powerful People, Amacom Books. Retrieved from http://iveybusinessjournal.com/topics/the-organization/negotiating-the-top-ten-ways-that-culture-can-affect-your-negotiation#.U-B8tbccRl8 (accessed on 5/8/14)

Strategies which respect culture

Strategies for resolving conflict should be found that respect culture. These may include:

consultative process

protecting individuals from shame

disciplining within the organisation

non-confrontational approach

using traditional methods if appropriate

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mediation within Community Justice Centres[1]

Mediation for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people has been a priority of the Community Justice Centres since the inception of the CJCs in 1983.

CJC has services to help Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people solve their disagreements. Aboriginal mediators are available to help you solve a wide range of conflicts. They can also come out to your community or group and talk to you about what mediation is and the types of services they offer.

[1] NSW Government. (2012). Justice Lawlink, Mediation for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People. Retrieved from http://www.cjc.nsw.gov.au/cjc/com_justice_mediation/com_justice_mediation_atsi.html, accessed on 6 August 2014

4.4. Confirm mutual agreement to strategies and required outcomes with all relevant stakeholders

After a negotiation, it is very helpful to clarify things in writing and confirm a new timetable as soon as possible. Assess what took place during the negotiation so you can learn from your experience and strengthen your negotiation skills for the next time.

5. Evaluate Responses

Evaluate and review effectiveness of response according to legal and organisational requirements.

As already mentioned, a clear understanding of your organisational policies and procedures is essential so that you can properly evaluate responses in accordance with the rules. In addition, this will assist you in complying with accurate recording of incidents and report writing. It may be that there are also debriefing processes and stress management support services or processes in place to assist staff in dealing with conflict incidents.

All these areas are important for employee and detainee health and safety, as well as ensuring compliance with governing laws.

Evaluating organisational processes

The process an organisation uses to resolve conflict must be continually evaluated so that the organisation can determine whether it is meeting its obligations to its members (if applicable), staff and to the wider community.

Questions managers might ask during this review process include:

has the integrity of the organisation and its individuals been maintained?

are the parties involved satisfied with the outcome?

have the parties involved been kept advised of progress of conflict resolution?

have the parties involved clearly stated their positions so everyone knows where they stand?

has the process strengthened or weakened the organisation?

If answers to these questions indicate a need for processes to be improved, make sure this is done. Learn from mistakes and keep communications open.

Evaluation can include:

feedback from parties involved in conflict;

looking at the number of grievances; and

listing mistakes made.

5.1. Provide accurate and constructive observations of incidents and their contributing factors when reviewing and debriefing the situation

If there is a conflict incident it is really important that organisational polices are complied with so that there is an accurate recording of what occurred. It may be that a detainee makes a complaint about how an incident was handled. It may be that somebody was injured and some sort of an inquiry (organisational or legal) needs to be conducted to see exactly what occurred and if there were any breaches of the law or procedures. For employees, having an accurate recording of the observations from the incident can assist in the debrief process. It can also assist in developing organisational policies – it may be that something needs to be changed for the next time a similar situation arises.

Western Australia: example of a Policy Directive

Please refer “Annexure C” for an example of an organisational Policy Directive on ‘procedures for reporting incidents’.

There is also provision for ‘Post incident actions and considerations’ where there is reference to the organisation’s Organisational Debriefing Guidelines. The focus of the debriefing process is to share information and provide reassurance to the employee.

5.2. Provide and maintain records and reports in accordance with organisational requirements

As mentioned, keeping accurate records and reports following a conflict situation is very important. These records may need to be used as part of an organisational debrief or self-evaluation process. It may be that there is an allegation of a breach of the law in which case these documents may need to be used as evidence in court. Each organisation will have its own polices about recording and reporting conflict situations or incidents. These policies will reflect the current laws relating to the institutional setting.

Western Australia: example of a Policy Directive

Please refer “Annexure D” for an example of an organisational Policy Directive on ‘procedures for reporting incidents’. This directive has been issued by the Western Australian Department of Corrective Services. Incidents and Critical Incidents are defined and the procedures are set out in section 6. Incident reports are described as being an ‘integral part’ of operations (page 4). There is detail about how to prepare the report, what information needs to be included and the processes involved for complying with the reporting procedures.

5.3. Recognise effects of stress in self and manage using recognised stress management techniques

Positive and negative stress

When we are feeling a little pushed or excited, but are in control of the situation, this is known as ‘positive’ stress. This is manageable stress that keeps life interesting. ‘Negative’ stress is when there is more happening in our lives than we can cope with. If we are feeling things are getting out of our control, our stress levels are too high.

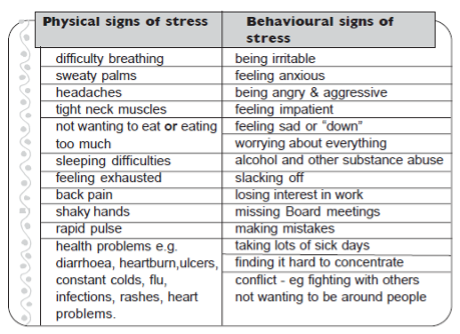

Recognising stress

It is important to recognise when you and others around you are experiencing stress. Become familiar with emotional warning signs of stress.

Once stress has been recognised, something can be done about it. Stress should not be swept under the carpet or left to grow. Stress that has built up over time can have bad effects on individuals and the organisation as a whole.

Signs of stress

You should always be on the lookout for signs of stress in yourself and others. Stress can show itself in physical ways as well as in the way we behave

Individual differences

While there are some common signs of stress, it is important to realise that everyone is different. Your signs of stress might be different from someone else’s. For example, some people lose their appetite for food when they are stressed, others eat more. Some withdraw and say nothing, others get very angry. Usually a person’s behaviour changes when they are stressed, so if you notice someone around you behaving differently or complaining of health problems, be alert to the possibility that they may be feeling stress. You should also be aware of your own signs of stress so that you can find ways to reduce the stress when you feel it happening.

Confidentiality & trust

People who are experiencing stress need to be supported and encouraged. They need to know that whatever they tell you will be kept confidential.

People need to know they can trust you not to tell others if they open up their hearts and tell you private things. If you do not feel comfortable in dealing with an issue, let the person know straight away. Suggest who they could go to for help. Reassure them anything they have told you will be kept confidential.

Culturally appropriate strategies

It is important to identify culturally appropriate ways to relieve or prevent stress. It is always better to try to prevent stress rather than try to deal with stress once it gets out of hand. Culturally appropriate strategies to relieve stress can include:

· working together

· sharing the load

· supporting others

· choosing appropriate person to deal with stress

· talking about problems

· listening to others

· allowing time off for cultural and family obligations

· providing training & mentoring

· dealing with issues in a non-threatening way

· allowing time to make decisions

· understanding historical context of stress

· avoiding singling people out and causing shame by discussing their stress in front of others

· considering the feelings of others and support people who are experiencing stress.

Strategies for reducing stress

There are many ways stress can be reduced. The following are some strategies your organisation should be using to reduce stress: building teamwork planning and setting clear goals prioritising sharing workloads putting on extra resources renegotiating timelines managing conflict using family support time out organising social activities providing training & mentoring networking awareness raising recognising negative behaviours expressing feelings reward and praise good work be a good role model.

Organisations

Once an organisation has agreed on appropriate strategies to reduce stress, they should be put in place. Everyone has a role to play in the reduction of stress in an organisation. Stress can affect everyone, so all Board Members, management and staff should be seeking ways to prevent and reduce stress. You need to pay particular attention to finding ways to reduce your own stress. Otherwise you will not be able to function well as a member of your organisation.

The nature of the work in a custodial setting can increase a person’s risk of being stressed. It is really important that organisation policies in detention centres, correctional centres or prisons, community corrections offices, justice administration offices and on work sites where detainees, prisoners or offenders are under statutory supervision recognise the importance of managing stress. This is especially important in the context of conflict management and for people who are regularly dealing with conflict situations and / or traumatic events. Special stress management processes are often incorporated into organisational polices to assist employees.

Queensland Example: ‘Managing Traumatic Events at Work’

Please refer “Annexure E” for an example of an organisational Policy Directive on ‘Managing Traumatic Events at Work’. The purpose of this policy is described as being aimed at minimising the effects of a traumatic event’s (including conflict situations) on staff. The policy is aimed at ensuring the equity, safety and health of their agency staff. You will see that section 2.1 describes examples of traumatic events. Then sections 9, 10 and 11 deal with debriefing processes for staff, including engaging with family (see section 8).

This policy deals with serious examples of conflict situations, but you can see that the overall approach and aim of the policy is to reduce the stress and manage the stress that has been caused by the situation.

6. Annexure A

7. Annexure B Use of Force – NSW Ombudsman Report

8. Annexure C Incidents – WA Department of Corrective Services – Policy Directive 41: Reporting of Incidents and additional notification

9. Annexure D Incident Reporting – WA Department of Corrective Services – Policy Directive 41: Reporting of Incidents and additional notification

10. Annexure E Stress Management – Queensland Corrective Services Procedure

11. Prepare for mediation

What is Mediation?

Mediation is one form of alternative dispute resolution (ADR).

ADR refers to various dispute resolution processes and techniques to assist parties to a dispute to come to an agreement with the help of a third party thus avoiding the need to make a complaint to a court.

In more recent times, however, ADR has been adopted by courts as a tool to help settle disputes alongside the court system itself. ADR has been adopted as a useful tool by most Australian court systems.

Outside the

court context, ADR has also become a familiar feature for dealing with disputes

in business and community situations.

Mediation is a process that promotes the self-determination of participants and in which participants, with the support of a mediator:

(a) communicate with each other, exchange information and seek understanding

(b) identify, clarify and explore interests, issues and underlying needs

(c) consider their alternatives

(d) generate and evaluate options

(e) negotiate with each other; and

(f) reach and make their own decisions.

11.1. Role of the Mediator

The mediator facilitates a process. The mediator cannot make a decision about the outcome of the dispute, or who is right or wrong.

A mediator can help people to:

o Identify the issues in dispute

o Consider options for dealing with the issues

o Reach their own negotiated solution.

A mediator should:

o Guide participants through discussions about their concerns and issues to help them to explore whether there are solutions that may be acceptable to all involved

o Be impartial and not take sides

o Ensure that all relevant concerns and issues in dispute are addressed

o Assist to break down the relevant concerns and issues in dispute into manageable parts

o Create an environment where all participants have an equal opportunity to be heard

o Ensure that discussions do not get out of control

o Assist participants to examine options for resolving the dispute

o Assist participants to write down the details of any concluded negotiated agreement.

A mediator should not:

o Provide legal advice

o Take sides

o Decide who is right or wrong

o Make a decision on behalf of participants

o Make suggestions about what should happen after the conclusion of the mediation

o Force participants to reach an agreement.

In some cases, mediation is not possible because, for example:

- A mediation is a voluntary process (unless ordered by a court) and one or more potential participants to a dispute may not agree to participation (mediation is voluntary unless a court has made an order that you are to mediate)

- There might be safety concerns or reason to fear violence

- A person involved in the dispute is unable to speak up for themselves or negotiate on their own behalf and this makes mediation unsuitable

- The issue affects the wider community, so that there might be a 'public interest' in having a court decide it, or

- The issues in the dispute are very complex or otherwise not suitable for mediation.

The mediator should:

- Explain the mediation process and set the guidelines for how it will work

- Ensure each person has a chance to talk, be heard and respond to the issues

- Keep everyone focused on communicating and resolving the dispute

- Ask questions to help people identify and communicate about what their goals and desires are and why they feel that way

- Help clarify the issues and suggest ways of discussing the dispute

- Help the people in dispute develop options and consider whether possible solutions are realistic

- Try to assist the parties reach an agreement where appropriate and make sure everyone understands any agreement reached, and

- Refer you to other helpful services if required.

The mediator must not:

- Take sides, make decisions or suggest solutions - this is for you and the other participants to do

- Tell you what you should agree to do - you decide what to do, including whether to stay at mediation

- Decide who is right or wrong - the focus is on finding a solution that everyone can live with, not making a judgment

- Give legal, financial or other expert advice - you can get advice before, during and after mediation if you choose, and

- Provide counselling - you can get counselling or other support before, during and after mediation if you choose.

If all the participants agree, mediation may also involve support people.

11.2. Identify key stakeholders and analyse dispute to be resolved

When is mediation used (i.e. who are the parties and what types of disputes are likely to be at issue)?

Mediation can help resolve disputes involving:

• neighbours

• communities or associations

• money matters

• families

• schools

• workplaces, and

• businesses.

Some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people may be concerned about the prospect of mediation, considering it to be a European form of dispute resolution and thus culturally alienating and unhelpful. The reasons for this can be various e.g.:

· The perceived ‘pseudo-judicialising’ of the mediation process

· Language barriers

· Communication barriers (e.g. challenges in accessing reliable and private telephone and internet services)

· Financial challenges

· Transport constraints etc.

It is very important therefore for the mediator to take such concerns into consideration. The mediator also needs to be aware that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander dispute resolution systems predated the arrival of the British in 1788 by thousands of years.[1] It is in this regard that Bauman and Pope point out the following:

The ability of Indigenous communities to deal with conflict in ways that reflect their local practice and reinforce local community authority not only help make communities safer and more enjoyable places to live, they also go some way to addressing the sources of dysfunction and systemic conflict.[2]

The mediator of a dispute involving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people needs to ensure that the parties are involved in the development of a suitable mediation model with which they are comfortable.

In order to effectively incorporate Indigenous culture and experience into a mediation practice, the Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service Co-operative Ltd in its paper “Exploring culturally appropriate dispute resolution for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples” [3] emphasises specific issues to be considered when mediating a dispute involving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island people:

Preparation

Bishop encourages the mediator to properly prepare the parties so that culture can be incorporated effectively into the mediation experience.[4] In this regard, Bishop states that, by outlining ‘a sufficiently certain communication plan pre-mediation session, parties may be able to experience more cultural comfort as to the mediation process, and may enable a mediator to design a mediation plan that will better accommodate the particular needs and demands of the parties’ in dispute’.[5]

In this regard, it may be important for the mediator to ensure that, before commencing the mediation, there is an appropriate recognition of kinship and acknowledgement of traditional Indigenous ancestors.

Venue

The mediator must remain sensitive to schedule the mediation session(s) at an appropriate venue. This is especially important for remote communities where access to services is difficult.[6]

Neutrality and impartiality

Given the detailed and complex structures of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander family networks, kinship obligations, and far-reaching community knowledge, it may be difficult to find an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mediator who is completely neutral.[7]

In some cases, therefore, it may be difficult to locate a mediator who is a ‘neutral third party’ for a mediation between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander parties. The issue should be decided on a ‘case by case basis and flexibility is necessary in this regard.[8]

Respected figures within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are often valued for their ability to remain impartial. Nevertheless, care needs to be taken to remind the participants that the mediator’s role is to ‘assist’ the parties and not to ‘solve’ their dispute.[9]

Confidentiality

The requirement of confidentiality is often central to a successful mediation process.

The reason for this is to encourage the parties to negotiate honestly, without the fear of having the dialogue used as evidence in subsequent court proceedings.

However, this can be a challenge in some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander disputes due to close kinship ties, living arrangements, and the multi-party nature of many such disputes. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community(ies) involved may be very aware of the dispute and its history.[10]

Sauvé states that mediated outcomes of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander disputes were often made public to bring the ‘moral weight of the community’ to bear on the agreement.[11] In a sense, the community itself ‘owned’ the dispute. The typical requirement of confidentiality can run counter to this notion.[12]

Pringle recommends flexibility in relation to confidentiality.[13] Kelly emphasises that mainstream mediations will also have exceptions to confidentiality e.g. where employees involved in a dispute agree to notify management of the outcome of the mediation.[14]

Voluntary attendance

The mediator must remain alert to the possibility that the parties may not attend the mediation in a voluntary capacity. Noble refers to example of community leaders pressuring parties into attending a mediation.[15]

‘Gratuitous concurrence’ refers to the situation where an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participant may agree to a direct question that they have not understood.[16] Waterford refers to the:

…a well-known phenomenon of Aboriginal English and traditional Aboriginal language speakers is ‘gratuitous concurrence’, where a listener indicates consent or agreement to a person in a position of authority, even when they do not agree with what is being said (or sometimes when they do not understand what is being asked).[17]

The mediator must be aware of this phenomenon. It can be addressed by the mediator making use of open-ended questions, thus allowing the participant to state their own point of view in a narrative form, rather than indicate agreement or disagreement to a statement made by another person.

Language

In a paper by the Family Law Council of Australia, the Northern Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency (NAAJA) submitted that ‘complex language is often used in family dispute resolution proceedings. Many of our clients leave mediations with limited understanding of what transpired in the mediation’.[18]

Since the 1960’s, educators have officially recognised a difference between Aboriginal English and Standard Australian English.

Aboriginal English can include differences in grammar, vocabulary, meaning, use and style depending on the location of the particular community.

Again, this challenge can be overcome by employing open-ended questioning or even engaging an Aboriginal English interpreter if necessary.[19] [20]

Non-verbal communication barriers

Mainstream mediators may regard silence as a sign of evasiveness.

With a mediation involving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participants the mediators must remain sensitive to non-verbal communication barriers. This includes the need to wait until a participant volunteers certain information and to respect silence when it occurs.

Silence should not be misinterpreted and used against the relevant party.

Strong language

Sensitivity to the potential use of strong language may be necessary.

Strong language may not be intended as an attack on the other party or upon the mediator themselves.[21]

Mediators may need to be open to the possibility that a participant may walk out of the room after a moment of ‘elevated emotion’.[22]

Taboo topics

The mediator should aim to avoid reference to topics that are considered to be ‘taboo’ e.g. genitals, pregnancy and speaking the names of recently deceased.

The participants may also exhibit a reluctance to discuss ‘men’s business’ and ‘women’s business’ with each other. In this light, it may be important for such matters to be discussed with a same gender mediator.[23]

[1] Croft, H., The Use of Alternative Dispute Resolution Methods within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Communities (2015) https://docplayer.net/26214025-The-use-of-alternative-dispute-resolution-methods-within-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-communities.html.

[2] Bauman, T and Pope, J., Solid Work You Mob Are Doing – Case Studies in Indigenous Dispute Resolution and Conflict Management in Australia (Report to the National Alternative Dispute Resolution Advisory Council, FCA Indigenous Dispute Resolution & Conflict Management Case Study Project, ACT, 2009) 115.

[3] The Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service Co-operative Ltd , “Exploring culturally appropriate dispute resolution for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples” https://balitngulu.org.au/assets/2015/06/Alternative-Dispute-Resoution-ADR.pdf.

[4] Bishop, H,. Influences Impacting on Aboriginal ADR Processes in the Context of Social and Cultural Perspectives (2000).

[5] Bishop, H,. Influences Impacting on Aboriginal ADR Processes in the Context of Social and Cultural Perspectives (2000).

[6] The Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service Co-Operative, Exploring culturally appropriate dispute resolution for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples (12 April 2015) https://balitngulu.org.au/assets/2015/06/Alternative-Dispute-Resoution-ADR.pdf .

[7] Cunneen C, Luff J, Menzies K, & Ralph N (2005) ‘Indigenous Family Mediation: The New South Wales ATSIFAM Program’ Australian Indigenous Law Reporter 9(1).

[8] Cunneen C, Luff J, Menzies K, & Ralph N (2005) ‘Indigenous Family Mediation: The New South Wales ATSIFAM Program’ Australian Indigenous Law Reporter 9(1).

[9] It must be noted that not all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander parties will prefer an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander mediator. Some parties may prefer a totally neutral mediator who possesses no community connections. If a dispute in a small community affects all community members, an ‘external’ mediator may be preferred. Also, kinship obligations can create family and/or cultural pressure on an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mediator to take a particular side. Cunneen C, Luff J, Menzies K, & Ralph N (2005) ‘Indigenous Family Mediation: The New South Wales ATSIFAM Program’ Australian Indigenous Law Reporter 9(1).

[10] Cunneen C, Luff J, Menzies K, & Ralph N (2005) ‘Indigenous Family Mediation: The New South Wales ATSIFAM Program’ Australian Indigenous Law Reporter 9(1).

[11] Sauvé M (1996) ‘Mediation: Towards an Aboriginal Conceptualisation’ Aboriginal Law Bulletin3(80): 10.

[12] Cunneen C, Luff J, Menzies K, & Ralph N (2005) ‘Indigenous Family Mediation: The New South Wales ATSIFAM Program’ Australian Indigenous Law Reporter 9(1).

[13] Pringle K L (1996) ‘Aboriginal Mediation: One Step Towards Re-Empowerment’ Australian Dispute Resolution Journal 7(4): 253. It may be necessary to remove or amend the confidentiality clause in any mediation agreement.

[14] Kelly L (2007) ‘Mediation in Aboriginal Communities: Familiar Dilemmas, Fresh Developments’ Indigenous Law Bulletin 28(6): 14.

[15] Noble K (1994) Alternative Dispute Resolution: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Initiatives Paper presented at the Third International Conference in Australia on Alternative Dispute Resolution, Surfers Paradise, 1-2 October.

[16] Roberts F (2008) Aboriginal English in the Courts Kit Fitzroy: Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service Co-operative Limited.

[17] Waterford, K., "Cross-cultural disputes: guidance for Australian mediators" [2017] AULA 43; (2017) 141 http://classic.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/PrecedentAULA/2017/43.html.

[18] North Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency, Submission to NT Government, Aboriginal Clients in the Family Law System (2011) 5.

[19] Roberts F (2008) Aboriginal English in the Courts Kit Fitzroy: Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service Co-operative Limited.

[20] Pringle K L (1996) ‘Aboriginal Mediation: One Step Towards Re-Empowerment’ Australian Dispute Resolution Journal 7(4): 253.

[21] National Alternative Dispute Resolution Advisory Council (2006) Indigenous Dispute Resolution and Conflict Management Canberra: National Alternative Dispute Resolution Advisory Council .

[22] Pringle K L (1996) ‘Aboriginal Mediation: One Step Towards Re-Empowerment’ Australian Dispute Resolution Journal 7(4): 253.

[23] Pringle K L (1996) ‘Aboriginal Mediation: One Step Towards Re-Empowerment’ Australian Dispute Resolution Journal 7(4): 253.

12. Conduct mediation interview

Establish the Ground Rules

The mediator explains the rules and process involved in mediation.

First, meet with each participant separately, to outline what they can expect from you and from the process. Make sure that they are both willing to participate – mediation won't work if you try to impose it!

Agree on some ground rules for the next stage of the process. These might include asking each person to come prepared with some solutions or ideas, listening with an open mind, and avoiding interruptions. It's important that you build trust with both participants, and make them feel safe enough to talk openly and truthfully with you and with one another.

Sourced on 28/7/22: https://www.mindtools.com/pages/article/mediation.htm

Statements by the parties

Each party has the opportunity to describe the dispute.

Identification of the dispute

The mediator will ask the parties questions in order to gain a better understanding of the conflict.

Private caucuses

The mediator will conduct private meetings with the parties to obtain a better understanding of each party's side and to assess possible solutions.

Find a quiet room in a neutral location where you won't be disturbed, away from the rest of the team.

Meeting with the participants individually will allow them to share their side of the story with you openly and honestly. Use active listening skills and open questions to get to the root of the problem. Reflect upon and paraphrase what your team members tell you, to show that you understand their points of view.

Use your emotional intelligence to identify the underlying cause of the conflict, and pay attention to each participant's body language to help you to get a better sense of their state of mind.

Be prepared to encounter a range of strong feelings, from fear and distress to anger, and even a wish for revenge. But avoid shutting these feelings down – this might be the first time that your team members have fully expressed the impact of the conflict, and it will likely give you valuable clues to its cause.

Then ask each person what they hope to gain from the mediation. Remind them that it's not about winning, but about finding a practical resolution that suits everyone who's involved.

Sourced on 28/7/22: https://www.mindtools.com/pages/article/mediation.htm

Negotiation

The mediator will help the parties reach an agreeable solution.

Once both sides have had time to reflect, arrange a joint meeting. Open the session on a positive note, by thanking them for being open to resolving the conflict. Remind them of the ground rules, summarize the situation, and then set out the main areas of agreement and disagreement.

Explore every issue in turn, and encourage the participants to express how they feel to one another. Make sure that they have equal time to talk, and that they can express themselves fully and without interruption. If they become defensive or aggressive, look for ways to bring the conversation back to the main problem at hand. Encourage them to empathize with one another, and to improve their understanding of one another's point of view by asking questions themselves.

Once both sides have given their views, shift their attention from the past to the future.

Go over the points that were raised in your meetings, and try to identify areas where they have at least some shared opinions. Resolve these issues first, as a “quick win” will help to build positive momentum, and bolster both sides' confidence that a workable solution can be found.

Ask participants to brainstorm solutions and encourage win-win negotiation to make sure that they reach a solution that they're happy with. If a suggestion is unreasonable, ask the initiator what he would consider to be reasonable, and whether he thinks that the other party would agree.

Sourced on 28/7/22: https://www.mindtools.com/pages/article/mediation.htm

13. Document outcomes of mediation interview

Written agreement

If the parties reach a resolution, the mediator may confirm the agreement in writing and ask the parties to sign this agreement.

Take notes during all of the meetings that you mediate and, once the participants have reached a solution, write that up as a formal agreement. Make sure that the agreement is easy to understand and that actions are SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound).

Help to avoid any confusion or further disagreement by checking that your language is neutral, free from jargon, and clear for all. Read the agreement back to both parties to make sure that they fully understand what will be expected from them, and to clarify any points that they do not understand or that are too general or vague.

You might even consider getting each person to sign the agreement. This can add weight and finality to the outcome, and help to increase their accountability. But mediation is designed to be a relatively informal process, and you could undermine this by pushing too hard.

It's time to bring the mediation to a close. Give the participants copies of the agreed statement, and clearly explain what will be expected from them once they're back in the workplace.

Take some time to prepare, together, how to overcome obstacles to implementing the agreement, and to explore options for dealing with them. Summarize the next steps, offer your continued support as a mediator, and thank both parties for their help and cooperation.

Sourced on 28/7/22: https://www.mindtools.com/pages/article/mediation.htm

14. Services and Agencies Relevant to Mediation

Legal Aid NSW

The Family Dispute Resolution Service of Legal Aid NSW helps people to resolve their family law dispute without going to court by inviting the parties involved in the dispute to attend a mediation.

Sourced on 28/7/22: https://www.legalaid.nsw.gov.au/what-we-do/family-law/family-dispute-resolution

NSW Department of Fair Trading

Fair Trading provides a free mediation service concerning housing and property, which often assists in achieving a resolution without needing to resort to more formal and costlier avenues such as the Tribunal or courts.

NSW Small Business Commission

The NSW Small Business Commission offers a cost-effective commercial mediation service to help solve many types of disputes without the high cost and delays inherent in going to court.

https://www.smallbusiness.nsw.gov.au/what-we-do/mediation

The Law Society of NSW

Family Relationships Online

https://www.familyrelationships.gov.au/separation/family-mediation-dispute-resolution

Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia

Assistance with dispute resolution can be obtained through Legal Aid, Community Legal Centres or private legal practitioners.

Legal Aid is generally subject to means and assets tests as a well as restrictions on the type of matters that assistance can be provided for.

Community Legal Centres can provide free advice and some, but not all, can assist you with representation. A list of Community Legal Centres in each state and territory can be found on the Community Legal Centres Australia website.

Private legal practitioners work on a fee-for-service basis. Each state and territory has a Law Society or Institute (for solicitors) as well as a Bar Association (for barristers). Law Societies and Bar Associations often operate:

· referral services to a legal practitioner who can help

· mediation services, and/or

· maintain lists of arbitrators.

Law Society websites all have a ‘Find a Solicitor’ and ‘Find a Mediator’ function to search for solicitors and mediators in your area.

The following webpages provide information on external dispute resolution services:

· Family Relationships Advice Line

· Attorney-General’s Department Family Dispute Resolution Register

· Australian Institute of Family Law Arbitrators and Mediators

· Legal aid bodies in your relevant state or territory

· Attorney-General's Department: amica - An Online Dispute Resolution Tool

Community Justice Centres

Community Justice Centres (CJC) provides free mediation services. CJC mediators can mediate in different sorts of matters including neighbour disputes, community disputes, small debts and disputes at work.

You can arrange mediation at CJC by contacting CJC.

If you ask CJC to arrange mediation, CJC staff will contact the other people involved in your dispute and invite them to mediate. If the other people agree, mediation may be arranged as soon as one week after your first call. Mediation at CJC is free.

The CJC website provides a range of resources to help you prepare for mediation.

People Community Justice Centres

People Community Justice Centres (CJC) has a program to help Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people mediate disputes and it has Aboriginal mediators. For more information on this program, go to the CJC website.

Fair Work Commission

If you make an unfair dismissal or general protections application to the Fair Work Commission (the Commission), you will be asked to attend a conciliation conference before your case goes to a hearing. A conciliation conference is very similar to mediation and the information on this site about preparing for mediation will help you prepare for a conciliation conference. For more information on conciliation in employment matters, go to the Fair Work Commission website.

If you make a complaint to the Fair Work Ombudsman you may also be asked to attend a mediation conference. For more information on this process, go to the Fair Work Ombudsman website.

Family Dispute Resolution

Family Dispute Resolution is a process for resolving disputes about the care of children in family matters.