M4 - Learner Manual

| Site: | Tranby National Indigenous Adult Education & Training |

| Course: | 10861NAT Diploma of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Advocacy 2024 |

| Book: | M4 - Learner Manual |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Tuesday, 16 December 2025, 6:23 PM |

Table of contents

- 1. Introduction

- 2. The Importance of Land in Indigenous Culture

- 3. Native Title in Australia

- 4. A Chronology of Land Rights and Native Title in Australia

- 5. The Common Law: Some important cases for Native Title

- 6. Comparing Land Rights & Native Title Processes

- 7. The Role of Courts, Tribunals and Aboriginal Land Councils

1. Introduction

Module 4 includes one units of competency:

NAT10861009 Provide assistance to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people making claims on land

Click to download PDF Learner Manual Module 4

The materials for this unit commence by looking at the strong connection between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture and land. This section addresses the impact of colonisation on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. It also looks at a number of important aspects of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture in Australia.

Next the material explores the principles of native title in Australia. This includes a consideration of the various laws (statutory and common law), policies and procedures that have an impact on this field. A chronological overview of the development of land rights and native title has been included in the materials.

A number of important Common Law decisions are considered and the impact they had on native title. Following this, a comparison is made of the Land Rights and native title processes. Finally, the materials examine the specific role of the Australian Federal Court, the National Native Title Tribunal & Aboriginal Land Councils in the above two processes.

2. The Importance of Land in Indigenous Culture

The impact of land on cultural practice

For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, the land is at the core of all spirituality, beliefs, and culture and as such is central to the issues that are important to Indigenous Australians today.[1]

Land is recognised by Aboriginal people as having a value far beyond its economic worth, as former Chairman of the Northern Land Council, Mr Galarrwuy Yunupingu, explains it:[2]

“For Aboriginal people there is literally no life without the land. The land is where our ancestors came from in the Dreamtime, and it is where we shall return. The land binds our fathers, ourselves and our children together. If we lose our land, we have literally lost our lives and spirits, and no amount of social welfare or compensation can ever make it up to us.”[3]

Aboriginal knowledge of the land, water, and culture (often referred to as lore) is passed down from generation to generation, thus forming an extensive matrix of people, totemic, social and spiritual connection with land and country.[4]

“We cultivated our land, but in a way different from the white man. We endeavoured to live with the land; they seemed to live off it. I was taught to preserve, never to destroy”[5]- Tom Dystra

Aboriginal people have established and developed a uniquely strong connection with their land and country since time immemorial; their culture is embedded in the land.[6]

The impact of loss of land on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture

The significance of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s connection to land has been very poorly understood by non-Indigenous Australians ever since colonisation in 1788. A considerable lack of understanding and/or respect for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture has been evident in much of the policies of successive governments since this time of dispossession. From the killing times of the 19th century, to the protectionist era ending in the late 1960’s and the assimilationist era in force until 1972, Aboriginal historian and poet Kevin Gilbert had to this to say in 1973 about Australia’s black history:

“Ever since the invasion of our country by English soldiers and then colonists in the late eighteenth century, Aborigines have endured a history of land theft, attempted racial extermination, oppression, denial of basic human rights, actual and de facto slavery, ridicule, denigration, inequality and paternalism. Concurrently, we suffered the destruction of our entire way of life- spiritual, emotional, social and economic.”[7]

Resistance to occupation of Aboriginal land was immediate. Numerous stories of Aboriginal warriors and resistance fighters permeate the history of Australia’s colonisation. One of the most famous stories in New South Wales is that of Pemulwuy, a proud Bidjigal leader of the Eora Nation who led counter-raids against those responsible for the injustices being suffered by his people at the time.

In addition to the tragic loss of life of Aboriginal people over battles for land, many lives were lost from disease, a situation exacerbated by the reduced access to shelter and food.

This history of forced resettlement onto reserves, the separation of families, and placement of thousands of Aboriginal children into institutions has had a devastating impact on Aboriginal people, culture, and their connection to the land. The dispossession and removal impacted Aboriginal culture in the following ways:

- Loss of identity, as their identity was connected to the land.

- Separation from kinship groups was destructive for the kinship system and resulted in the loss of language.

- Children removed from their families in an attempt to assimilate them were unable to maintain their cultural identity or learn their traditional language and practices.

- Sacred sites were unable to be visited or protected.

- Ceremonies and traditional practices were often prohibited or unable to be performed in the traditional way at sacred sites.

It has continuously been recognised that the loss of their land and culture, dating back to white settlement, is still evident in the disadvantages that Aboriginal people continue to experience today. Current reports and statistics suggest that Aboriginal people are the most disadvantaged group within Australian society as they are over-represented in the criminal justice and child protection system, have the worst health and housing rates, lowest educational, occupational and economic status compared to any other Australian group.[8]

[1] Australian Government. (2008). Australian Indigenous cultural heritage. [online] Available at http://australia.gov.au/about-australia/australian-story/austn-indigenous-cultural-heritage, [Accessed 26/9/14]

[2] Queensland Studies Authority. (2007). The History of Aboriginal Land Rights in Australia (1800s-1980s).[online]. Available at from https://www.qcaa.qld.edu.au/downloads/approach/indigenous_res006_0712.pdf, [Accessed 26/9/14]

[3] Australian Government. (2008). Australian Indigenous cultural heritage. [online] Available at http://australia.gov.au/about-australia/australian-story/austn-indigenous-cultural-heritage, [Accessed 26/9/14]

[4] Queensland Museum and Queensland Government. (2010). Aboriginal Peoples’ connection to land. [online Available at http://www.qm.qld.gov.au/Find+out+about/Aboriginal+and+Torres+Strait+Islander+Cultures/Land#.VCTDy2eSygR, [Accessed 26/9/14]

[5] Australian Government. (2008). Australian Indigenous cultural heritage. [online] Available at http://australia.gov.au/about-australia/australian-story/austn-indigenous-cultural-heritagem, [Accessed 26/9/14]

[6] Queensland Museum and Queensland Government. (2010). Aboriginal Peoples’ connection to land. [online] Available at http://www.qm.qld.gov.au/Find+out+about/Aboriginal+and+Torres+Strait+Islander+Cultures/Land#.VCTDy2eSygR, [Accessed 26/9/14]

[7]McRae, H et al. (2009). Indigenous Legal Issues: Commentary and Material, Thomas Reuters, p 13

[8] Human Rights Law Centre.(2011). National Human Rights Action Plan – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. [online] Available at http://www.humanrightsactionplan.org.au/nhrap/focus-area/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-peoples, [Accessed 26/9/14]

3. Native Title in Australia

Native title describes the rights and interests of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in land under their traditional laws and customs.

Native title is sometimes referred to as a ‘bundle of rights’ and may include rights to:

- live on the area

- access the area for traditional purposes, like camping or to do ceremonies

- visit and protect important places and sites

- hunt, fish and gather food or traditional resources like water, wood, and ochre

- teach law and custom on country

In some cases, native title includes the right to possess and occupy an area to the exclusion of all others (often called ‘exclusive possession’). This includes the right to control access to, and use of, the area concerned. However, this right can only be exercised over certain parts of Australia, such as unallocated or vacant Crown land and some areas already held by, or for, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians.

The content of that bundle of rights will depend on the native title holder’s traditional laws and customs and the capacity of Australian law to recognise the native title claimant’s rights and interests.

Therefore, native title does not give Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people:

- Ownership (as recognised in Torrens Title freehold). As such, native title claimant groups cannot sell or assign the land;

- The power to take away other people’s valid right to the land (e.g. mining lease, pastoralist);

- The right to prevent development[1]

Under the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth), mining companies and other developers are required to negotiate with native title holders and others with a potential interest in the land before commencing any development. The interests of native title holders may well be affected by mining or other industries operating on native title land. Native title holders do not have the power to say no to such developments; instead they have a right to negotiate.

The outcome of successful negotiations may take the form of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Land Use Agreements (ILUAs). If the parties cannot reach a negotiated agreement within certain time limits the issue can be subject to compulsory mediation and determination by the National Native Title Tribunal.

The type of evidence required to make a native title application

In lodging an application for native title, the claimants accept the onus of presenting sufficient evidence to establish a connection to the land under their traditional law and customs.[2] Usually evidence will be presented which outlines[3]:

· Whether any members of the native title claim group currently reside on the land.

· How the natural resources of the land are used including information about flora, fauna and other resources.

· The presence of sacred sites or the continuing performance of ceremonies on the land;

· How the responsibility of the land has continued and been conveyed across generations.

· Any other evidence which indicates how they have adapted and maintained contact with the land since British colonisation.

Where 3rd parties propose to develop land subject to a native title claim or determination

Where a person proposes to do something that affects native title over land which is subject to a registered native title claim or determined native title rights or interests, the claimants or holders must be notified. This triggers certain processes under the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth):

• the “right to negotiate” process, which requires the state and the proponent to negotiate “in good faith” with the claimants or holders in order to obtain their agreement to the proposal (generally resulting in execution of either an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Land Use Agreement, which is then registered and has the effect of law between the parties, or a land access agreement, which is an unregistered agreement), failing which the matter can be referred to the National Native Title Tribunal for determination;

• an expedited process which can apply where the proposal has a minimal impact on the land; or

• a notification and consultation process where the rights to be granted relate to infrastructure.

If a grant of interest in land is made without the appropriate process under the NTA being followed, this can result in the invalidity of that grant and may diminish any native title rights in the land.[4]

National Registers maintaining native title records

The Native Title Registrar (the Registrar) maintains three registers of important information related to native title. These registers are as follows:

· Register of Native Title Claims which contains information about native title claimant applications that have satisfied the conditions for registration (the registration test) set out in s.190A of the Native Title Act 1993 (Commonwealth) (the Act)

· National Native Title Register which contains information about all approved determinations of native title in Australia

· Register of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Land Use Agreements which contains information about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander land use agreements (ILUAs) made between people who hold, or may hold, native title in the area and other people, organisations or governments.[5]

[1] Central Land Council.(2008). Native Title Act made simple. [online] Available at http://www.clc.org.au/files/pdf/CLC_native_title_brochure.pdf, [Accessed 3/10/14]

[2] Native Title and Indigenous Land Services. (2003). Guide to compiling a connection report for native title claims in Queensland, [online] Available at http://www.aiatsis.gov.au/_files/ntru/researchthemes/connection/connectionrequirements/QLDConnectionGuide.pdf [Accessed 3/10/14]

[3] Native Title and Indigenous Land Services. (2003). Guide to compiling a connection report for native title claims in Queensland, p.4 [online] http://www.aiatsis.gov.au/_files/ntru/researchthemes/connection/connectionrequirements/QLDConnectionGuide.pdf [Accessed 3/10/14]

[4] Gilbert Tobin Lawyers < http://www.gtlaw.com.au/publications/doing-business-in-australia/native-title-and-indigenous-heritage/>

[5] National Native Title Tribunal, ‘About the Native Title Tribunal’s registers’, < http://www.nntt.gov.au/News-and-Communications/Publications/Documents/Booklets/About_the_registers_April_2009.pdf>

4. A Chronology of Land Rights and Native Title in Australia

In 1835, John Batman a non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander man signed two ‘treaties’ with the local Aboriginal elders of the Kulin tribe to ‘purchase’ 240,000 hectares of land, located between what is now known as Melbourne and Bellarine Peninsula. The land, which was significant farming terrain for Batman, was almost all of the Kulin’s ancestral land. Batman’s ‘purchase’ of the land was based on European concepts of land ownership and legal contracts, concepts that were foreign to the Aboriginal Kulin people. The Kulin people, similar to other Aboriginal tribes of the time, did not view land in terms of possession but rather land for them was about belonging.[1]

In response to this treaty and similar arrangements between settlers and Aboriginal people, the New South Wales Governor of the time, Richard Bourke, immediately issued a proclamation in August 1835 declaring that the British Crown, not Aboriginal people, owned the land of Australia and thus that only it could sell or distribute land. An additional proclamation was issued stating that people who attempted to possess land without the authority of the Government would be considered trespassers and thereby liable to punishment. In effect, the proclamations overrode the legitimacy of the treaty between Batman and the Kulin people and reinforced the notion that Australian land belonged to no one before British taking possession of it.[2]

A report by the House of Commons in 1837 recognised that Aboriginal people had rights in the land.[3] However “despite all the evidence to the contrary, British law continued to insist that Australia was uninhabited, that no-one was in possession [prior to colonisation].”[4] This was referred to as the legal doctrine of terra nullius. The law that was applied across Australia continued to reflect Bourke’s proclamation until the landmark decision in the Mabo v The State of Queensland [1992] HCA 23 (Mabo) case.[5]

In 1861, the New South Wales Government enacted the Crown Lands Acts which introduced free selection of Crown land. It allowed people to select up to 320 acres of land before it was surveyed on the condition that they would pay a deposit of one-quarter of the price and would live on the land for three years.[6] It was intended to increase farming and agriculture of the land. The Acts also limited the use of Crown lands by Aboriginal people.

In the second half of the 19th Century, Torres Strait Islanders also lost their independence when the Queensland Government annexed the Torres Strait Islands.

In 1966 stockmen and women at Wave Hill led by Vincent Lingiari, a Gurindji man, walked-off in protest against intolerable working conditions and inadequate wages. They established a camp at Watti Creek and demanded the return of some of their traditional lands.

The Gurindji strike was not the first or the only demand by Aboriginal people for the return of their lands - but it was the first one to attract wide public support within Australia for Land Rights. It led to the 1972 Labor Party’s policy on Land Rights and the enactment of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1976 (NT) – the first statutory recognition of the inalienable right Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have to this land.

In 1972 Labor leader Gough Whitlam said: “We will legislate to give Aboriginal Land Rights – because all of us as Australians are diminished while the Aborigines are denied their rightful place in this nation”. In February 1973, Whitlam appointed Justice Woodward to report on the appropriate way to recognise Aboriginal Land Rights in the Commonwealth controlled Northern Territory.

In 1974 Woodward presented his final report. The report stated that the aim of land rights was to do a simple justice to the Aboriginal people who had been deprived of their land without their consent and without compensation. He proposed procedures for claiming land and the conditions associated with tenure, in particular it was suggested that Aboriginal land should be granted as inalienable freehold title (could not be sold, mortgaged or disposed of in any way) and that the title should be held communally. [7]

In 1975, Prime Minister Gough Whitlam handed back title of the traditional lands of the Gurindji people.

On the 26 January 1977, the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth) came into effect. The Act recognised that Aboriginal people had rights to land. As a result, it established a process to enable local Aboriginal Land Councils to lodge a claim on behalf of the Aboriginal community to reclaim their land.

In 1983, New South Wales enacted their version of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act. While legislation provided some rights to Aboriginal people, the legal myth that Australia was ‘terra nullius’ continued. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people continued to fight for recognition of their traditional rights, and in 1992 a major land rights victory was won through the courts.

In 1992, the High Court of Australia ruled in the Mabo (No 2) case that native title exists over particular kinds of land – unalienated Crown land, national parks and reserves – and that Australia was never ‘terra nullius’. This single ruling overturned a legal and historical lie that had stood for more than two centuries. The case recognised that since colonization Aboriginal people had been dispossessed of their rightful land.

In 1993, in response to the Mabo decision the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) was enacted. The Native Title Act establishes the procedure for making native title claims. It has been extensively amended in 1998, 2007, and again in 2009.[8] The preamble to the Native Title Act acknowledges the following:

“Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait Islanders were the inhabitants of Australia before European settlement. They have been progressively dispossessed of their lands. This dispossession occurred largely without compensation, and successive governments have failed to reach a lasting and equitable agreement with Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait Islanders concerning the use of their lands. As a consequence, Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait Islanders have become, as a group, the most disadvantaged in Australian society.”[9]

In 1996, the High Court of Australia decided the matter of Wik Peoples v Queensland [1996] HCA 40 [10]. The Wik people of Western Cape York Peninsula in Far North Queensland were one of the first groups to launch legal action for recognition of their rights after the decision in Mabo (No 2). The HC, by a 4:3 majority, held that the grant of pastoral leases under the QLD Land Acts did not necessarily extinguish native title. This in effect confirmed that native title might co-exist with another interest in the same land to the extent that the two were legally consistent with each other

The 1998 amendments to the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) included among others, the following changes:

· Native Title claimants had to satisfy a stringent and retrospective registration test before “right to negotiate” (RTN) on mining proposals or compulsory acquisitions.

· States territories may replace the RTN with weaker processes.

· Native Title claimants have reduced procedural rights concerning mineral exploitation

· Reduced say of Native Title holders in government activities

· Easier for state governments to compulsorily acquire co-existing native title rights

On 11 August 1998 the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD) concluded that whilst the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) was delicately balanced between the rights of Indigenous and non-Indigenous title holders, the amended Act appeared to create legal certainty for Governments and third parties at the expense of Indigenous title.

In 2002, the matter of Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v Victoria (2002) 214 CLR 422 went before the High Court of Australia. This provided for a fundamental examination of what is needed to prove traditional connection to country, sufficient to achieve a positive determination of native title under 223(1) Native Title Act 1993 (Cth). The bar is obviously set very high, but Gleeson CJ, Gummow and Hayne JJ said: “demonstrating some change to, or adaptation of, traditional law or custom or some interruption of enjoyment or exercise of native title rights or interest in the period between the Crown asserting sovereignty and the present will not necessarily be fatal to a native title claim…”

[1] State Library of Victoria. (2014). Batman’s Treaty. [online] Available at http://ergo.slv.vic.gov.au/explore-history/colonial-melbourne/pioneers/batmans-treaty [Accessed 26/9/14

[2] Australian Government. (2008). European discovery and the colonisation of Australia. [online] Available at http://australia.gov.au/about-australia/australian-story/european-discovery-and-colonisation [Accessed 26/9/14]

[3] Australian Government. (2008). European discovery and the colonisation of Australia. [online] Available at http://australia.gov.au/about-australia/australian-story/european-discovery-and-colonisation [Accessed 26/9/14]

[4] Harold Reynolds. (1992). Law of the Land. As cited in: National Museum of Australia. (2007). The Struggle for Land Rights. [online] Available at http://indigenousrights.net.au/land_rights [Accessed 26/9/14]

[5] Australian Government. (2008). European discovery and the colonisation of Australia. [online] Available at http://australia.gov.au/about-australia/australian-story/european-discovery-and-colonisation [Accessed 26/9/14]

[6] NSW Government – State Records. (2003). Archives In Brief 93 – Background to conditional purchase of Crown land. [online] Available at http://www.records.nsw.gov.au/state-archives/guides-and-finding-aids/archives-in-brief/archives-in-brief-93 [Accessed 26/9/14]

[7] Central Land Council (2006) http://learnline.cdu.edu.au/tourism/uluru/downloads/CLC_Lands%20rights%20act.pdf

[8] The Aurora project (2014) What is Native Title. Retrieved from http://www.auroraproject.com.au/what_is_native_title#How_can_native_title_be_proved_ first accessed 26/9/2014

[9] Native Title Act (Cth) 1993; http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/nta1993147/

[10] Wik Peoples v Queensland ("Pastoral Leases case") [1996] HCA 40; (1996) 187 CLR 1; (1996) 141 ALR 129; (1996) 71 ALJR 173 (23 December 1996)

5. The Common Law: Some important cases for Native Title

Mabo v The State of Queensland (No 2)[1992] HCA 23

In 1982, Eddie Mabo, a Meriam man, and four other Torres Strait Islander people went to the High Court of Australia claiming that their island, Mer (Murray Island), had been continuously inhabited and exclusively possessed by them, therefore, they were the true owners. They acknowledged that the British Crown had exercised sovereignty when it annexed the islands, but claimed that their land rights had not been validly extinguished.

On 3 June 1992 the High Court of Australia handed down its decision in, ruling that the treatment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander property rights based on the principle of terra nullius was wrong and racist. Sadly, Eddie Mabo never heard the ruling, as he died of cancer in January of that year. [1]

The Court ruled that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ownership of land has survived where it has not been extinguished by a valid act of Government and where Aboriginal people have maintained traditional law and links with the land.

This legal recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ownership is called ‘native title’. The Court ruled that in each case native title must be determined by reference to the traditions and customary law of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander owners of the land.

The judgment of the High Court in the Mabo case inserted the legal doctrine of Native Title into Australian law. In recognising the traditional rights of the Meriam people to their islands in the eastern Torres Strait, the court also held that native title existed for all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia prior to Cook's instructions and the establishment of the British Colony of New South Wales in 1788. This decision altered the foundation of land law in Australia- debunking the legal myth of terra nullius.

In recognising that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia had a prior title to land taken by the Crown since Cook's declaration of possession in 1770, the court held that this title exists today in any portion of land where it has not legally been extinguished.

Section 223 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) was drafted primarily from the judgment of Brennan J in the Mabo case. However, the courts have repeatedly made it clear that the Native Title Act, not the common law, is the primary authority on any native title inquiry, cases such as Mabo are merely contextual.[2] Therefore, the Federal Court’s process of determining native title is basically a statutory interpretation exercise[3].

Wik Peoples v Queensland [1996] HCA 40

In 1996, in the Wik decision[4] the High Court by a 4:3 majority held that pastoral leases do not necessarily extinguish any native title interest that may have survived. The court held that that native title rights could coexist on land held by pastoral leaseholders but that where there is conflict between native title rights and interests and the rights of pastoralists, the latter will prevail.

The High Court decided that:

- A pastoral lease does not necessarily give rights of exclusive possession on the pastoralist. Native title rights could ‘co-exist’ alongside the rights of pastoralists on cattle and sheep stations.

- The rights and obligations of the pastoralist depend on the terms of the lease and the law under which it was granted.

- The mere grant of a pastoral lease does not necessarily extinguish any remaining native title rights.

- When pastoralists and Aboriginal rights were in conflict, the pastoralists’ rights would prevail, giving pastoralists certainty to continue with grazing and related activities but not necessarily ‘exclusive possession’ of the land [5]

The Wik decision led to great controversy at the time. Despite the fact that pastoralists did not really lose any rights, farmers and conservative leaders demanded that native title be extinguished, or wiped out, on pastoral leases altogether. Previous to this decision many people had believed that all such leases completely extinguished native title.[6]

Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v State of Victoria [2002]

The Yorta Yorta peoples lodged a native title determination application with the National Native Title Tribunal (NNTT) on 21 February 1994. The Yorta Yorta claimed native title in the public lands and waters (‘the claim area’) within their original homelands. The Yorta Yorta sought the right to possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of the claim area and its natural resources. Following unsuccessful mediation of the claim through the National Native Title Tribunal, the matter was heard before the Federal Court of Australia.

The Federal Court decision

The Federal Court dismissed the Yorta Yorta people’s application on the basis that:

“by 1881 those through whom the claimant group [sought] to establish native title were no longer in possession of their tribal lands and had, by force of the circumstances in which they found themselves, ceased to observe those laws and customs based on tradition which might otherwise have provided for the present native title claim”.[7]

One of the reasons for the decision of Justice Olney, was that in 1881, 42 men referred to as ‘Aboriginal natives’ who were ‘residents of the Murray River’ had signed a petition to the Governor of the Colony at the time seeking ‘farming assistance’. According to Olney J this was evidence of a departure from the traditional practices and customs.[8]

Following an unsuccessful appeal to the Full Court of the Federal Court of Australia, the Yorta Yorta People appealed to the High Court of Australia.

The High Court decision

A critical issue of the case was whether the Yorta Yorta people could demonstrate the requisite connection to the area through evidence of a continued observance of traditional law and custom.[9] Similar to Mabo (No 2) the court was divided over what satisfied the requirement of connection:

- The majority (Gleeson CJ, Gummow, and Hayne JJ) found that the acknowledgment and observance of traditional law and custom “must have continued substantially uninterrupted since sovereignty”[10] and that only those customs and laws which existed “before the assertion of sovereignty by the British Crown” were to be regarded as authentically traditional to satisfy the purposes of native title law.[11]

- Gaudron and Kirby JJ disagreed stating that section 233(1)(b) only required that there be a present connection to land and waters and that this connection did not need to be physical. It was argued that continuing occupancy could also be spiritual[12]… to the extent that they differ from past practices, the differences should constitute adaptations, alterations, modifications or extensions made in accordance with the shared values of the customs and practices of the people who acknowledge and observe those laws and customs”.[13]

However, in the end the majority of the High Court dismissed the Yorta Yorta people’s appeal and in doing so placed a positive obligation on future native title claimants to prove that their traditional law and customs have continued substantially uninterrupted since 1788.[14]

[1] Australian Museum, <http://australianmuseum.net.au/Indigenous-Australia-The-Land>

[2] See for example: Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v Victoria, (2002) 214 CLR 422, 31-2; Western Australia v Ward (2002) 213 CLR 1, 16.

[3] Lisa Strelein. (2009). as cited in Lisa Strelein. (2014). Reforming the requirements of proof: The Australian Law Reform Commission’s native title inquiry. Indigenous Law Bulletin,8(10) pp 6-10. [online] Available at http://www.ilc.unsw.edu.au/sites/ilc.unsw.edu.au/files/articles/8-10%20Lisa%20Strelein.pdf [Accessed 3/10/14]

[4] See note 25

[5] AIATSIS, Native Title Research Unit Resource Page, ‘Wik: coexistence, pastoral leases, mining, native title, and the ten point plan’, <http://aiatsis.gov.au/ntru/documents/WIKupdated.pdf>

[6] Reconciliation Australia. (n.d.). [online] Available at http://www.reconciliation.org.au/home/resources/factsheets/q-a-factsheets/native-title, [Accessed on 14/10/2014]

[7] Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v State of Victoria & Ors [1998] FCA 1606 at 121

[8] Ibid at 119-121

[9] Sean Brennan. (2003). Native Title in the High Court of Australia a decade after Mabo, [online] Available at www.gtcentre.unsw.edu.au/sites/.../brennanNativeTitleinHighCourt.doc [Accessed 10/10/14]

[10] See note 37 at [87] Gleeson CJ, Gummow and Hayne JJ

[11] Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v State of Victoria & Ors [2002] HCA 58 at 46

[12] Ibid at 103 and 104

[13] Native Title and Indigenous Land Services. (2003). Guide to compiling a connection report for native title claims in Queensland, p.4 [online] Available at http://www.aiatsis.gov.au/_files/ntru/researchthemes/connection/connectionrequirements/QLDConnectionGuide.pdf [Accessed 3/10/14]

[14] Peter Seidel. (2004). Native Title the struggle for justice for the Yorta Yorta nation, [online] Available at https://www.abl.com.au/ablattach/ALJ0404.pdf [Accessed 10/10/14 ]

6. Comparing Land Rights & Native Title Processes

Native title, although dealing with the subject of land rights, is very different from Land Rights as claimable under the Land Rights Acts of the various states and territories throughout Australia.

The original Northern Territory land rights model, as distinct from native title, was the first of its kind in Australia. Mick Dodson has described the legislation as “a resilient and uniquely powerful piece of legislation”.[1] The other states and territories have now also enacted their own Land Rights legislation. For instance, in New South Wales, the Minister who administers the Crown Lands Act 1989 (NSW), determines Aboriginal land claims under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW). If a claim is successful, land can be transferred in the form of freehold title to the claimant Aboriginal Land Council. The Aboriginal Land Council with the decision of members can develop and/or sell the land as long as it has received the appropriate approval of the New South Wales Aboriginal Land Council.

The key features of Aboriginal Land Rights schemes are that Aboriginal people are given strong title to land, which they do not receive through native title determinations, and are given control of vital decision-making over their land.[2]

The different legal tests

Under the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth):

In order to receive a determination of native title, and thus a determination that pre-existing rights in land survived colonisation and continue today, it must be proved that:

· The claimants have rights and interests in the land that are possessed under traditional laws acknowledged and traditional customs observed

· The people have maintained their connection with the land; and

· Their title has not been extinguished by legislation or any action of the executive arm of the government inconsistent with that title.

This is not a simple task. In fact it is quite an onerous process. Native title claim groups usually need to provide evidence about:

· The identity of the claimants

· Their traditional language

· Their connection to country and responsibilities to the land

· Their social and cultural system and the law and custom which is acknowledged and observed

· Their rights and interests in land and water, and

· Traditional activities carried out by claimants on their country.

This evidence is usually presented in the form of expert anthropological and historical reports and in affidavit statements provided directly by individual members of the native title claim group.[3]

What constitutes extinguishment?

The question of extinguishment is complex and involves consideration of common law and statute.[4]

The common law’s position on extinguishment began with the decision in Mabo (No 2) and has continued to develop in the Federal and High Court (see for example the Wik decision and the decision of Wilson v Anderson[5]). In Mabo, it was held that native title could be extinguished by a ‘clear and plain intention’ to extinguish native title. This is commonly achieved by:

1. A legislative provision expressed to extinguish native title.

2. An inconsistent grant of an interest in land over with native title subsists inconsistent with those rights.

3. Acquisition by the Crown of native title land.

Section 237A of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) states that extinguish, in relation to native title, means permanently extinguish the native title and thus that after it is extinguished it cannot be revived.[6]

Under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW):

The legal test for recognising Land Rights is very different from native title. To make a claim under land rights legislation, the claimant does not need to show a continuing connection to land through traditional customs and lore. The test for land rights evolves entirely around the nature of the land being claimed, namely whether the land can be classified as claimable Crown land.

Local Aboriginal Land Councils or the NSW Aboriginal Land Council, on behalf of local Aboriginal communities, are able to claim certain Crown lands and have them transferred to the Land Council in the form of freehold title. As compared to native title, this form of title gives Land Councils exclusive possession over the land and the right to dispose of it as they see fit (within the bounds of certain regulatory requirements).

What applications can be made and who by?

Under the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth):

The following table sets out the various claims that can be made and who may make such claims under the provisions of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth):

|

Applications |

||

|

Kind of application |

Application |

Persons who may make application |

|

Native title determination application |

Application, as mentioned in subsection 13(1), for a determination of native title in relation to an area for which there is no approved determination of native title. |

(1) A person or persons authorised by all the persons (the native title claim group) who, according to their traditional laws and customs, hold the common or group rights and interests comprising the particular native title claimed, provided the person or persons are also included in the native title claim group; or (2) A person who holds a non-native title interest in relation to the whole of the area in relation to which the determination is sought; or (3) The Commonwealth Minister; or (4) The State Minister or the Territory Minister, if the determination is sought in relation to an area within the jurisdictional limits of the State or Territory concerned. |

|

Revised native title determination application |

Application, as mentioned in subsection 13(1), for revocation or variation of an approved determination of native title, on the grounds set out in subsection 13(5). |

(1) The registered native title body corporate; or (2) The Commonwealth Minister; or (3) The State Minister or the Territory Minister, if the determination is sought in relation to an area within the jurisdictional limits of the State or Territory concerned; or (4) The Native Title Registrar. |

|

Compensation application |

Application under subsection 50(2)for a determination of compensation. |

(1) The registered native title body corporate (if any); or (2) A person or persons authorised by all the persons (the compensation claim group ) who claim to be entitled to the compensation, provided the person or persons are also included in the compensation claim group.

|

In every application, members of the native title claim group must be identified. This can be done by naming every member of the native title claim group or through naming the ancestors of the members, as members are usually related and descend from the same ancestors. Evidence must be presented that identifies the native title claim group as descendants of the traditional owners of the land before colonisation. This can be argued through presenting recorded historical, archaeological and anthropological information.[7] It is essential that the members are united by their cultural system of traditional law and custom and that the applicants are authorised to make the application by the traditional owners of the land.[8]

Under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW):

The Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW) provides only for the New South Wales Aboriginal Land Council (NSWALC) and Local Aboriginal Land Councils (LALCs) to make claims for claimable Crown lands[9].

- NSWALC may make a claim for land on its own behalf or on behalf of one or more LALCs- section 36(2)

- One or more LALCs may make a claim for land within its or their area or, with the approval of the Registrar, outside its or their area- section 36(3)

Individuals, organisations or traditional clans cannot make any claims independent of Aboriginal Land Councils.

The Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW) allows for LALCs to make claims over the following types of ‘claimable Crown lands’:

- Crown land able to be lawfully sold or leased

- Crown land not lawfully used or occupied,

- Crown land not needed or likely to be needed as residential land,

- Crown land not needed, nor likely to be needed, for an essential public purpose,

- The Crown land must not be subject of an application for a determination of native title or have been the subject of a successful application for native title

If a native title dispute goes to trial following failed mediation, it can be a long and complex process, involving difficult legal issues and extensive historical, archaeological and anthropological research. Claimants must establish a ‘continuing connection’ to the land and the ongoing survival of a decision-making group which operates under rules which are traced back to pre-colonisation.

Under Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW):

- A Local Aboriginal Land Council or the New South Wales Aboriginal Land Council lodges a land claim with the Registrar of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983. This claim is referred to the Crown Lands Minister/s for investigation and determination.

- Once the Ministers administering the Crown Lands Act 1983 (Cth) are satisfied that either whole or part of the land is claimable or not, the land is either granted or refused.

- Granted land is then transferred to the Land Council as freehold title.

[1] Ibid, p 223

[2] Ibid

[3] NTSCORP. (2012). What is native title: Fact sheet. [online] Available at http://www.ntscorp.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/What-Is-Native-Title-Fact-Sheet-2012-B.pdf [Accessed 3/10/2014]

[4] McRae, H et al. (2009), Indigenous Legal Issues: Commentary and Material, Thomas Reuters, p 370

[5] (2002) 213 CLR 401

[6] Native Title Act (Cth) 1993, s237A.

[7] Native Title and Indigenous Land Services (2003), Guide to compiling a connection report for native title claims in Queensland, p.4 Retrieved from http://www.aiatsis.gov.au/_files/ntru/researchthemes/connection/connectionrequirements/QLDConnectionGuide.pdf First accessed 3/10/14

[8] NTSCORP (2012) What is native title: Fact sheet. Retrieved from: http://www.ntscorp.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/What-Is-Native-Title-Fact-Sheet-2012-B.pdf first accessed 3/10/2014

[9] Office of the Registrar. (2012). Aboriginal Land Claims. [online] Available at http://www.oralra.nsw.gov.au/landclaims.html [Accessed 29/10/14]

7. The Role of Courts, Tribunals and Aboriginal Land Councils

The Federal Court

The Federal Court of Australia is responsible for the management of all applications made under the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) or a determination of native title or for compensation for the loss or impairment of native title. Those applications must be filed in the court.

As of 1 July 2012, the Federal Court is also responsible for mediation of native title claims and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Land Use Agreements (ILUA) negotiations related to native title claims mediation.

The court has wide powers to manage native title cases. It can:

- make directions about how the application is to be progressed

- decide whether or not the application should be referred to the National Native Title Tribunal or another appropriate person or body for mediation

- determine who are the ‘parties’ to the application

- adjourn the proceedings to allow time for the parties to negotiate

- make orders to ensure that native title applications which cover the same area are dealt with in one proceeding

- strike out or dismiss an application, which brings the case to an end

- set an application down for hearing

- make a determination recognising that native title does, or does not, exist

- decide whether compensation for the loss or impairment of native title should be paid.

The National Native Title Tribunal

The National Native Title Tribunal was set up under the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) and commenced operations in January 1994. The Tribunal is an independent statutory body with a wide range of statutory functions. It also provides services, including the provision of information and assistance to persons involved in native title processes and the wider public. The Tribunal administers part of the Future Act process - that is, generally, the process that deals with future acts relating to mining and some compulsory acquisitions.

The Tribunal's role includes mediating between parties, conducting inquiries and making decisions (called 'future act determinations') where parties can't reach agreements. In addition the Tribunal also manages ILUA negotiations that are not related to native title claims mediation.

The Tribunal also maintains the Registers of Native Title Claims, Native Title Determinations and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Land Use Agreements.[1]

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Land Use Agreements

ILUAs are voluntary agreements between native title groups and other interested parties about the use of land and waters. The ILUAs allow people to negotiate flexible agreements that suit their particular circumstances. ILUAs can be entered into whether or not there is a native title claim over the area.

ILUAs may cover topics such as:

- native title holders agreeing to future development

- access to an area and cultural heritage

- extinguishment or coexistence of native title

- compensation

- employment and economic opportunities for native title groups

Upon registration, ILUAs bind all parties, including native title holders, to the terms of the agreement.[2]

Aboriginal Land Councils

Local Aboriginal Land Councils are organisations run by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people that assist in the claiming and management of traditional lands. Many Land Councils include information about land rights and why land is important to Aboriginal people.[3] Land Councils give Aboriginal peoples a voice on issues affecting their lands, seas and communities.[4]

The Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 established the basis upon which Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory could claim rights to land based on traditional occupation. Under the Act, land councils represent Aboriginal people with “statutory authority”, i.e. authorised to enforce legislation on their behalf. Land councils also have responsibilities under the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) and the Pastoral Land Act 1992 (Cth).

There are 120 Local Aboriginal Land Councils located across NSW. Local Aboriginal Land Councils form the core of the organisational structure of the land rights network. Local Aboriginal Land Council boundaries do not necessarily affiliate with cultural or traditional association with country.[5] The boundaries of LALCs were set in the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW).[6] Section 87 of the Act allows for changes of these boundaries to be made.

The NSW Aboriginal Land Council is an independent statutory corporation constituted under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983. The Council is elected every four years and is comprised of nine counsellors representing nine regional areas.

Local Aboriginal Land Councils have many tasks and responsibilities including:

· To provide a strong voice for the Aboriginal people they represent

· To help Aboriginal people reclaim their country through appropriate avenues

· To help Aboriginal people manage their land

· To consult with landowners on mining activity, employment, development and other land use proposals

· To protect Aboriginal culture and sacred sites

· To assist with economic projects on Aboriginal land

· To promote community development and improve service delivery

· To fight for legal recognition of Aboriginal people’s rights

· To help resolve land disputes, native title claims and compensation cases

· To run the permit system for visitors to Aboriginal land and deal with illegal entry to lands

· To pursue cultural, social and economic independence for Aboriginal people[7]

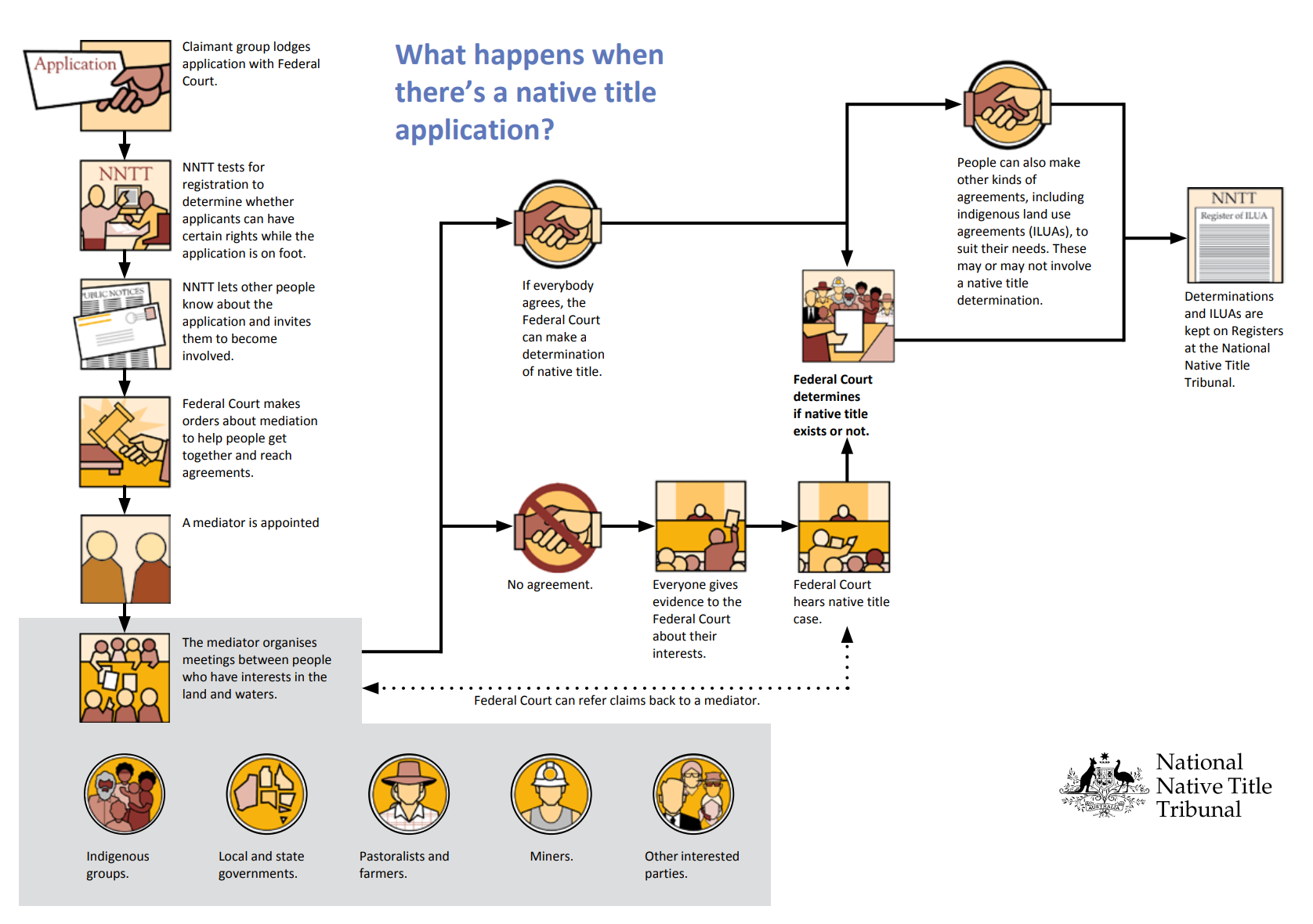

What Happens When There’s a Native Title Application?

[1] National Native Title Tribunal <http://www.nntt.gov.au/Information-about-native-title/Pages/The-Native-Title-Act.aspx>

[2] National Native Title Tribunal, Steps to an ILUA, [online] Available at http://www.nntt.gov.au/ILUAs/Pages/Registration-of-ILUAs.aspx [Accessed 3/10/14]

[3] ReconciliACTION Fact sheet <http://reconciliaction.org.au/nsw/education-kit/land-rights/>

[4]<http://australia.gov.au/people/indigenous-peoples/land-councils>

[5] Office of Communities, Aboriginal Affairs <http://www.aboriginalaffairs.nsw.gov.au/alra/nsw-and-local-aboriginal-land-councils/>

[6] Creative Spirits < http://www.creativespirits.info/aboriginalculture/selfdetermination/aboriginal-land-councils>

[7] Creative Spirits, Aboriginal Land Councils < http://www.creativespirits.info/aboriginalculture/selfdetermination/aboriginal-land-councils>