M3 - Learner Manual

| Site: | Tranby National Indigenous Adult Education & Training |

| Course: | 10861NAT Diploma of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Advocacy 2024 |

| Book: | M3 - Learner Manual |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Tuesday, 16 December 2025, 6:03 PM |

Table of contents

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Conduct simple legal research

- 2.1. The Australian Legal System

- 2.2. Characteristics of the Australian legal system

- 2.3. Constitutional Principles of the Westminster System

- 2.4. The Australian Constitution

- 2.5. Constitutional Recognition for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People

- 2.6. The Parliament and Legislative Process

- 2.7. How does Parliament pass a Bill

- 2.8. Types of Law: Public and Private Law

- 2.9. Diagram

- 2.10. Australian Courts of Law

- 2.11. Types of Legal Services

- 2.12. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Services

- 2.13. Legal Research

- 2.14. Requests for Information

- 2.15. Identify Relevant Sources of Legal Information

- 2.16. Finalising your research task

- 2.17. Research Resources

- 3. Manage responsibilities in relation to law reform

1. Introduction

Module 3 includes two units of competency:

BSBLEG423 Conduct simple legal research

NAT10861005 Manage responsibilities in relation to law reform

Click to download PDF Learner Manual Module 3

These units describe the knowledge and skills required to work under supervision to conduct simple legal research, locating relevant information and writing up a basic summary as well as how to monitor legislation that impacts Indigenous clients and organisations and to implement changes in workplace operations in response to legislative changes.

Specifically, we will be applying these skills in the context of dealing with Indigenous clients who need legal assistance.2. Conduct simple legal research

This unit describes the skills and knowledge required to work under supervision to conduct simple legal research locating relevant information and writing up a basic summary.

The unit applies to individuals who provide legal support services while under supervision. Its application in the workplace will be determined by the job role of the individual and the legislation, rules, regulations and codes of practice relevant to different jurisdictions.

2.1. The Australian Legal System

For a community or society to work, it needs to have a level of structure that applies to everyone and is understood by everyone. Law creates that structure and regulates the way in which people, organisations and governments behave.

A law is a rule that comes from a legitimate authority and applies to everyone. Laws are created to make sure that everyone understands what is expected of them as a member of society (their obligations) and what they can expect of others, including government (their rights).

Why do we have laws?

We have laws so that society can work effectively, to make sure that people or organisations are not able to use power, money or strength to take advantage of others or to make things better for themselves. We have laws to make sure that everyone understands their rights and obligations and the rights and obligations of others.

What is a ‘legal system’?

All countries

have a legal system of some sort. The ‘legal system’ is a broad term that

describes the laws we have, the process for making those laws, and the

processes for making sure the laws are followed. Our legal system reflects how

we, as Australians, behave and how we as a country expect people, organisations

and governments to behave with each other.

Who are the players in the Australian legal system?

We are all involved in the Australian legal system because it regulates what we may and may not do as members of the Australian community and because we elect those who make the laws:

- Commonwealth government – laws are passed by the Commonwealth Parliament, elected by all Australian citizens who are enrolled to vote;

- State/territory government – laws are passed by the state or territory parliament, elected by those Australian citizens who live in that state or territory who are enrolled to vote;

- Local government – local government by-laws are passed by the local councillors elected by people who live or own businesses within the local government area.

There are, however, some people and organisations at the heart of the legal system:

- The Federal, State and Territory parliaments;

- Courts and tribunals;

- Government departments;

- Government ministers;

- Police; and

- Lawyers (law firms, private practice, government departments).

Each has a different role to play in the legal system.

2.2. Characteristics of the Australian legal system

Snapshot

• English law – The colonial experience in Australia has greatly influenced the legal and political institutions which form the basic part of the current legal system. However, it was never simply imposed without modification. Colonialism requires an adaptation of those laws to the conditions that exist in the colony.

• Common law system – Australia’s system of law was modelled to a large degree on the British system.

• Federal system – Australia was established as a federal system in 1901. This was achieved by the Australian Constitution.

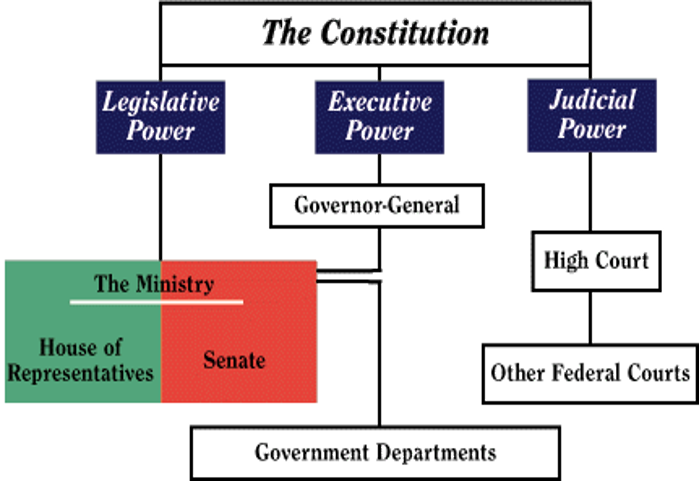

• Separation of powers – A predominant factor in the Australian legal system which is also taken to be a characteristic of many “Western” democracies such as the USA. The doctrine is entrenched in the Australian Constitution and describes categories of government into legislative, judicial and executive.

2.3. Constitutional Principles of the Westminster System

1. The rule of law

The rule of law has a number of meanings. As a historical concept, it essentially means that government should be through law, as opposed to the exercise of arbitrary (or random) power.

There is often an element of discretion (or responsibility) in the way in which general rules are applied to particular fact situations, and sometimes new questions of law have to be decided by the courts. But the rule of law means that the determination should be governed by reason rather than whim, prejudice or ad- hoc decision making. Common law therefore, provided for this logical examination.

A further aspect of the rule of law is the principle of equality before the law. That is, the wealth or status of the parties should be irrelevant to the outcome of the case.

2. Due process of law

“Due process” is an aspect of government originally established by the Magna Carta, a charter of English liberties granted by King John on June 15, 1215. The rule of law demands that the punishment of a person should only occur in accordance with proper legal process. This is a fundamental principle of all western legal systems.

Important aspects of “due process” in the criminal law are the:

- presumption of innocence; and

- right to trial by jury for serious offences.

3. The separation of powers

Many provisions of the Australian Constitution are based on long-standing principles of the British Parliamentary System. One of the most important of these is known as the Doctrine of Separation of Powers.

Its main principle is that there are three (3) distinct functions of the government, which should be separate and independent of each other – to ensure that each function is properly performed.

The three (3) functions of government are:

(a) Executive (PM and Cabinet)

(b) Legislature (Parliament)

(c) Judiciary (Courts)

Each “independent” arm of government acts as a check and balance on the other.

(a) The Executive

The Executive consists of the Prime Minister, assisted by a cabinet of senior ministers. The Executive is responsible for administering the laws and business of government through departments, statutory authorities and the defence forces.

(b) The Legislature

The power to pass law can be exercised only by the elected members of the two houses (House of Representatives & Senate) of the Federal Parliament and approved by the Governor-General.

(c) The Judiciary

The High Court and other Federal/State Courts have the judicial power to interpret laws and enforce them through penalties and fines.

If interpretation by the courts effectively creates new laws, they remain valid unless the parliament chooses to pass legislation that abolishes or modifies the judicial approach. For example, after the High Court decision in Mabo in 1992 the Commonwealth parliament passed the Native Title Act in 1993.

The meaning of “common law”[1]

The phrase “the common law” has three distinct meanings:

- It is a system of law – distinct from a civil law system

- It is a source of law – common law (also known as case law or judge-made law) as opposed to legislation/statute

- It is a historical source of law within the United Kingdom – common law as opposed to equity.

The common law system of law making came before the parliamentary system. It began in England in the 11th Century with the establishment by William the Conqueror, King of England, of the Kings Courts. The courts, in deciding local disputes, applied local customs. Over time, these customs became rules and were the basis for later courts to make decisions on similar disputes. The common law changed and developed as different types of disputes developed and different customs evolved.

The common law was the main body of law until the 17th century when the British Parliament increased its law-making power and activity (this resulted in more laws coming into being through Acts of Parliament). Common law is often referred to as ‘judge-made’ law.

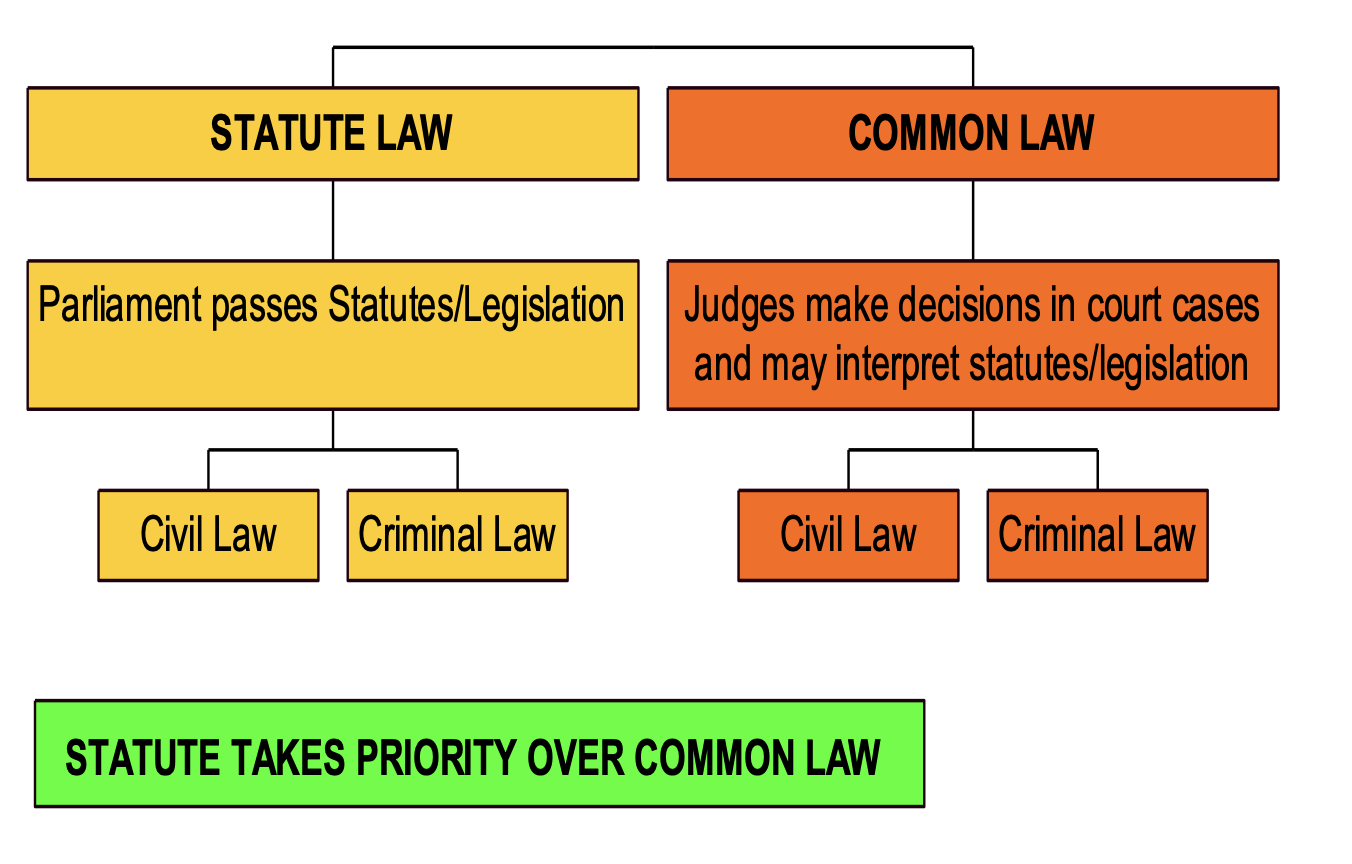

Common law is separate from statute law and does not rely on there being any Act of Parliament (or statute) underpinning it. While statute law is the main sources of law in Australia, the common law remains a vital and developing part of our legal system. Statute law always prevails over common law if there is a conflict.

The common law relies on the principle of precedent. This means that courts are to be guided by previous decisions of courts, particularly courts that have higher authority. So, the extent that common law is written down is that it is found in decisions of courts. This means that it can often be difficult to find the common law that applies to a situation, as it is not in one single decision of a court, but rather different parts of it are set out in different decisions.

The doctrine of precedent in Australia[2]

Some of the rules that make up the doctrine of precedent in Australia are:

- In the hierarchy of the court system, a decision of a higher court is binding on lower courts – for example, a decision of the Supreme Court of Western Australia is binding (must be followed) by the District Court of Western Australia, but would only be persuasive (do not have to follow) on Queensland or other state courts. Decisions from other common law countries such as the UK and New Zealand can also be persuasive but are not binding.

- Most courts are not bound to follow their own previous decisions, although they are expected to do so.

- The highest court in Australia, the High Court, is not bound to follow its own decisions.

- The decisions of courts outside Australia are not binding on Australian courts. However, Australian courts can refer to them for guidance or comparison if, for eg, a case is unusual or difficult.

- When a court makes a decision, it gives reasons for its decision. Another case with similar but not identical facts can be decided differently (that is, it can be distinguished). It is often said that ‘each case will be decided on its own facts’.

[1] See, Hughes, R.A., Leane, G.W.G., Clarke, A., Australian Legal Institutions 2nd ed Lawbook Co, Pyrmont, NSW 2003, p 46.

[2] See, Thomson Reuters, The Law Handbook 11th ed, Redfern Legal Centre Publishing, Pyrmont, NSW 1983 (1st published), p 3.

2.4. The Australian Constitution

The legal definition of a constitution is a law which prescribes rules for the governing body of a state or nation. That is, it sets out the powers of a parliament and government to make laws for a country.

Laws which are beyond those authorised by the constitution are said to be unconstitutional.

In Australia, each of the six State and Commonwealth Parliaments have a constitution which provides for their respective composition, powers and procedures. The territories do not have a constitution, instead they are granted limited self-government by the Commonwealth parliament.[1]

A constitution may either be written (as in the case of the States and the Commonwealth in Australia) or unwritten as in the case of the English constitution.

The 1967 constitutional referendum

The original Australian Constitution made two references to Australia's Indigenous persons in Sections 51 (xxvi) and 127:

51. The Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws for the peace, order, and good government of the Commonwealth with respect to: -

(xxvi.)

The people of any race, other than the aboriginal people in any State, for whom

it is deemed necessary to make special laws

127. In reckoning the numbers of the people of the Commonwealth, or of a

State or other part of the Commonwealth, aboriginal natives shall not be

counted.

Until 1967 each State made their own law for Aboriginals, which lead to different laws in each state. The Commonwealth had no power to make laws on Aboriginal issues because of section 51(26), which stated that:

“The people of any race, other than the aboriginal people in any State, for whom it is necessary to make special laws.”

In 1967 a change to the Australian Constitution was proposed that would mean that the Commonwealth and the States would have the power to make laws on Aboriginal issues and also led to Aboriginal people being included in the census.

The 1967 referendum came about because of strong campaigning by many people.

[1] See, for example the Northern Territory (Self-Government) Act 1978. Section 6 provides for the Legislative power of the Northern Territory Parliament: Subject to this Act, the Legislative Assembly has power, with the assent of the Administrator or the Governor-General, as provided by this Act, to make laws for the peace, order and good government of the Territory.

2.5. Constitutional Recognition for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People

Constitutional Recognition for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People

The Australian Constitution was drafted at a time when Australian land was considered to belong only to white settlement. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are not mentioned in the document. There are currently debates in the community about Constitutional Reform to recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the Australian Constitution.

The Victorian Constitution

The Victorian Constitution is the Constitution Act 1975 (VIC). It specifically recognises Aboriginal people.

Recognition of Aboriginal people

1A. Recognition of Aboriginal people

(1) The Parliament acknowledges that the events described in the preamble to

this Act occurred without proper consultation, recognition or involvement of

the Aboriginal people of Victoria.

(2) The Parliament recognises that Victoria's Aboriginal people, as the original custodians of the land on which the Colony of Victoria was established

(a) have a unique status as the descendants of Australia's first people; and

(b) have a spiritual, social, cultural and economic relationship with their traditional lands and waters within Victoria; and

(c) have made a unique and irreplaceable contribution to the identity and well-being of Victoria.

(3) The Parliament does not intend by this section-

(a) to create in any person any legal right or give rise to any civil cause of action; or

(b) to affect in any way the interpretation of this Act or of any other law in force in Victoria.

2.6. The Parliament and Legislative Process

Parliament is not the same thing as government. It is an institution which provides a form of legitimacy (validity) to government.

Government in Australia is based upon a party system in which one party or a coalition of parties has established the right to govern and introduce policies and laws for the period in which they are elected. The party system is not formally found in the various constitutions. Its role in relation to the Parliament and in government is created by convention (practice).

1. Bicameral nature of Australia’s Parliaments

The Parliaments at the federal and State levels (except Queensland) are bicameral. This means that there are two Houses of the Parliament. Therefore, Parliament consists of three elements – that is, the Crown and the two Houses.

In Queensland (QLD), the system is unicameral.

In the Territories (Australian Capital Territory (ACT) and Northern Territory (NT)), the system is unicameral.

Snapshot

At the federal or Commonwealth level, the Upper House is called the Senate. The Lower House is called the House of Representatives.

At the level of the States the Upper House is called the Legislative Council and the Lower House goes by different names:

The Legislative Assembly; in Western Australia, Victoria, New South Wales and QLD.

The House of Assembly: in Tasmania and South Australia.

2. Relationship between the Upper and Lower Houses

The Lower House – initiatives for laws begin here.

The Upper House – reviews the laws passed from the Lower House and therefore acts as a brake and provides an opportunity for more extensive deliberation on the actions and initiatives of the Lower House.

3. The functions of the House of Representatives

a) Makes laws

The process of making legislation begins at the House of Representatives.

To become law, bills must be passed by both the House of Representatives and the Senate.

b) Determines the Government

After an election the political party (or coalition of parties) which has the most Members in the House of Representatives becomes the ruling party.

Its leader becomes Prime Minister and other Ministers are appointed from among the party's Members and Senators. The Prime Minister and his/her Ministers form Cabinet.

c) Publicises and examines government administration

The House of Representatives debates legislation and ministerial policy statements; discusses matters of public importance; sets up committees of investigations; and asks questions of Ministers.

During question time, Members may ask Ministers questions without notice on matters relating to their work and responsibilities.

d) Represents the people

Members may present petitions from citizens and raise citizens' concerns and grievances in debate.

e) Controls government expenditure

The Government cannot collect taxes or spend money unless allowed by law through the passage of taxation and appropriation bills.

The Senate fulfils its role as a check on government by examining bills; delegated legislation; government administration; and government policy in general.

It does this by way of procedures utilised in the Senate chamber itself and through the operation of the Senate committee system.

There are 12 Senators from each of the six States, and two from the ACT and NT.

What is a statute?

The most important role of Parliaments is to make laws for their State, Territory or the Commonwealth. This is done through the parliamentary process of passing of legislation also known as: ‘Acts of Parliament’ / ‘Act’ / ‘Statute’.

1. Delegated (subordinate) legislation

Delegated legislation, as in the form of regulations to an Act, is not made by Parliament but by some designated nominee, such as a Minister or local government body.

The reasons for delegation are varied, including:

- Parliament’s lack of time and expertise to deal with details; and

- Rapidly changing circumstances.

Delegated legislation cannot contradict the Act that allowed for it to make a rule, regulation, or by-law.

2. What is a Bill?

While a State or Federal parliament is considering whether or not to pass an Act, the draft Act is called a Bill. A Bill must pass through parliament and receive Royal Assent before it becomes an Act.

3. When does an Act come into effect?

After a Bill becomes an Act, it does not necessarily commence immediately. It may commence on a date specified in the Act itself, or by proclamation (publication in the Government Gazette).

Different parts of an Act may commence at different times. If no time is specified, an Act commences 28 days after receiving the royal assent.

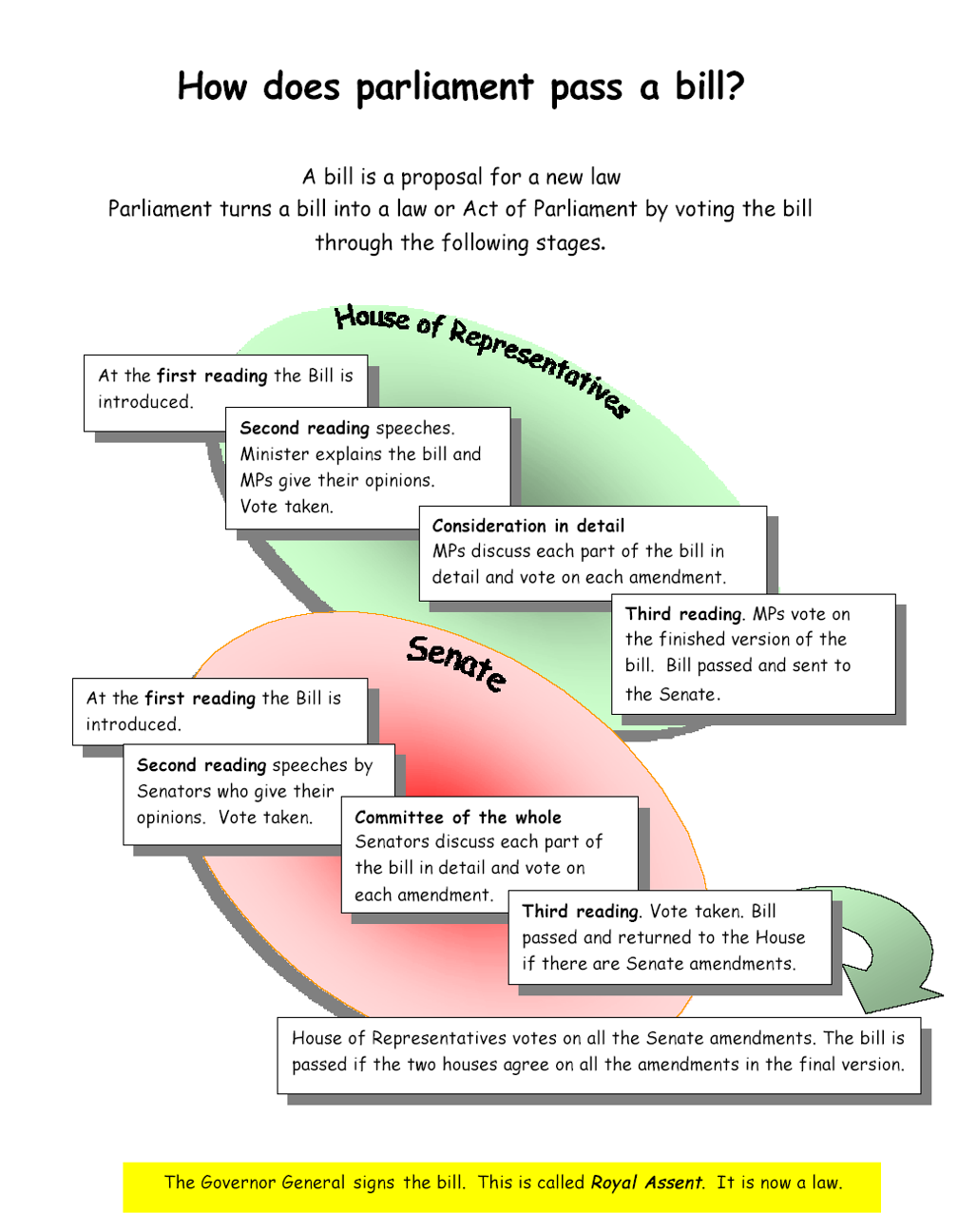

Once an Act commences, it becomes law.2.7. How does Parliament pass a Bill

2.8. Types of Law: Public and Private Law

Law can be divided up in a number of ways. We have already seen that we have ‘statute law’ and ‘common law’. We can also divide it into:- Public law; and

- Private law

- constitutional law

- administrative law

- international law

- taxation law

- criminal law

- industrial law

- contract law

- the law of torts

- property law

- succession and family law

- preservation of natural heritage

- the interaction between the environment and economy

- pollution caused by industry and individuals

- planning and development control of governments and government agencies

- use of resources

Under this system, public law deals with relations between individuals and the state. For example: A member of the public who challenges the government in relation to a right to vote.

Private law deals with relations between individuals (meaning individual people or organisations). For example: a contract between a business for the supply of services or the sale of a residential home between two families.

Areas of law classified as public include:

Areas of law classified as private/civil include:

Note: Broadly speaking, civil law is all law that is not criminal law. Administrative law is typically classified under Public law but there is some opinion that it is Private law.

Taxation law

The right to levy taxes against its citizens is regarded as one of the basic political powers of an independent state. Taxation is concerned with the interrelationship of the citizen and the State.

Administrative law

This area of law deals with regulation of relationships between the citizen and public officials, especially the bureaucracy.

Administrative law provides for specific ways in which people affected by government action can get information about and challenge that action. For example, individuals can make an application under freedom of information law to get access to government records. This may be records that the government holds about the applicant, or records about government actions or decisions that affect the applicant, or it can be records that there is a public interest in the government making available.

The Commonwealth, States and the ACT have laws dealing with freedom of information. These Acts are all called the Freedom of Information Acts. The Federal Act is the Freedom of Information Act 1982 (Cth). The NSW Act is the Freedom of Information Act 1989 (NSW). The NSW Act applies not only to information held by government departments, but also to information held by government agencies and by local government.

All government departments, agencies and local government have a process for making an application under freedom of information law. While there is usually an application fee, this fee can be waived in certain circumstances, such as if the person making the application can’t afford to pay the fee.

Administrative law cases are often dealt with by specialist tribunals, but the decisions can be reviewed by courts.

International law

International law is an area of public law because it involves interaction between the principles of different legal systems or between the citizens of different legal systems. These can only be settled at the public level of the legal system.

Environmental law

Environmental law is primarily public law in that it is, for the most part, a regulatory regime with respect to a number of issues such as those relating to:

It also includes an element of private law in that a number of common law actions, such as nuisance, may be an environmental concern.

Environment Protection Agencies exist at the federal and state level.

Commercial law

Commercial law is also known as business law which covers also corporate law. It is a body of law that governs business and commercial transactions. It is often considered to be a branch of civil law and deals with issues of both private law and public law.

Commercial law includes regulation of corporate contracts, hiring practices, and the manufacture and sales of consumer goods.

Criminal law

A crime, or offence, is an action that is against criminal laws that reflect society’s expectations of personal conduct, such as stealing, assault, fraud, failing to lodge tax returns, and polluting.

The government has the role of prosecuting or enforcing the criminal law against a person or company, usually through the police, the Director of Public Prosecutions or some other government body, such as the NSW Environmental Protection Authority.

A person who is being prosecuted in criminal law is called the defendant or the accused.

Offences can be divided into:

1. Indictable – offences which are serious and normally heard before a judge, or judge and jury in the District or Supreme Courts.

2. Summary – offences which are less serious and be decided by a Magistrate or local court.

Usually in order to decide that a crime has been committed, the court has to decide that the person has committed an act (‘actus reus’) and intended to commit the act knowing that it was wrong (‘mens rea’). However, for some crimes, there is no requirement that the person intended to do the act. These are known as ‘strict liability’ crimes.

The accused is innocent until proven guilty by a court. This is known as the ‘presumption of innocence’, so in the media the accused is referred to the alleged offender.

In criminal law, the burden of proof (or onus) of proof is on the prosecution. This means that the onus on proving guilt rests with the prosecution. A person cannot be found guilty of a crime unless the decision maker is satisfied that the prosecutor has proved ‘beyond reasonable doubt’ that the person committed the crime.

The defendant or accused does not have to say anything – right to silence. That is, the defendant cannot be compelled to give evidence. No conclusion can be drawn from the silence of the accused, although the defendant can be compelled to give their name and address to the police officer when arrested.

Until relatively recently an accused could not be tried for the same offence twice - this principle is referred to as double jeopardy - however this is no longer the case.

While the above legal principles apply to all people, some rules for certain Indigenous people have been developed to apply to criminal investigation by the police.

In the Northern Territory these special rules apply for interrogation of Aboriginal people. For example, there should be a 'prisoners friend' present; the caution should be read back by the accused; the questions should not be leading; etc.

These rules are called the Anunga Rules because they are based on the case of

R v Anunga (1976) 11 ALR 412.

The most common penalties ordered by courts when a person or organisation is found to be guilty of a criminal offence are orders to:

- Pay an amount of money to the government (e.g. a fine); or

- Spend a period of time in prison; or

- Do unpaid work that is needed in the community.

Civil law

Civil law deals with the regulation of private conduct between individuals, organisation and government agencies. Everyday dealings such as entering into an agreement by taking a ticket in a carpark, or clicking on “I agree” to internet terms and conditions.

Unlike criminal law, most civil laws are found in common law rather than statute law.

Most civil law cases deal with individuals or companies, often for doing something that is alleged to be unfair, harmful, or against an agreement.

A person bringing a case is called a plaintiff or, sometimes, an applicant or complainant. A person against whom an action is taken is called a defendant or respondent.

The standard of proof to which a person must prove their allegations is ‘on the balance of probabilities’, meaning it must be proved that something is more likely than not to have happened.

In a civil case, the plaintiff or applicant can seek an order for damages or compensation from the defendant, or an order that some conduct of the defendant be required, stopped, or altered. For example, an injunction to prevent the defendant from selling a house.

Civil disputes can be dealt with in courts, or in specialist tribunals set up to deal with specific civil law matters. An example of a tribunal that deals with civil disputes is the NSW Consumer, Trader and Tenancy Tribunal.

Contract law

Contract law encompasses any laws or regulations directed toward enforcing certain promises. In Australia contract law is primarily regulated by the 'common law', but increasingly statutes are supplementing the common law of contract - particularly in relation to consumer protection.

Family law

The Australian family law system is made up of a number of different elements with different areas of responsibility. It is much broader than the courts. It also embraces the many service providers and individuals who help families to resolve legal, financial and emotional problems and is centred around family members themselves.

As well as the Family Courts of Australia and Western Australia, the Federal Magistrates Court and State Magistrates courts, they include Centrelink, the Child Support Agency and other government agencies at national and State and local levels, community based organisations, private practitioners, advocacy groups and volunteers.

The Australian Government Attorney-General's Department administers policy regarding family law through the Family Law Branch and Marriage and Inter-country Adoption Branches. This Branch provides information on specific aspects of the family.

A Comparison Between Criminal Law and Civil Law |

||

|

|

Criminal |

Civil

|

|

Aim |

To protect society |

To protect the rights of the individual

|

|

Standing |

A breach of criminal law allows authorities to intervene |

The plaintiff needs to be the injured party

|

|

Burden of proof

|

Lies with the state/prosecution |

Lies with the plaintiff |

|

Standard of proof |

The prosecution must prove its case beyond reasonable doubt |

The plaintiff must prove on the balance of probabilities that their rights were infringed and damage resulted

|

|

Procedure |

A crime is committed, an investigation of the alleged crime takes place, a person is charged with an offence and then the accused (the person charged) is prosecuted by the state in a criminal court |

A person’s rights are infringed and evidence is collected as to damages caused, the defendant issued with a writ to attend court and the plaintiff sues the defendant in a civil court

|

|

Outcome |

Court finds a defendant guilty or not guilty. The defendant is punished by the court (for example, by fine, bond, imprisonment or some other sanction) |

The court finds the defendant liable or not liable. The plaintiff is awarded damages, an injunction or fulfilment of a contract against the defendant

|

|

Liability |

Crimes against property, the person and the state, public order or regulatory offences |

Torts, negligence, nuisance, defamation, assault, battery and breach of contracts

|

2.9. Diagram

2.10. Australian Courts of Law

1. State and Territory Courts

At the state and territory level the courts are divided into 3 categories:

1. Local Courts (lower courts)

2. District Courts (intermediate courts)

3. Supreme Courts

The complexity of the legal matter or the seriousness of the criminal offence has a bearing on the court in which a case will be heard so that the more complex or serious the case, the higher the court level. Decisions that are made by courts at the lower levels can be appealed against at a higher level.

The lower courts hear minor civil, criminal and family law cases. The lower courts can only hear matters of civil disputes where the amount of money they can award does not exceed a certain limit, and in criminal cases, where the size of the penalty such as a jail sentence, will not exceed a certain time period. For example, in the Small Claims Division of the Local Court in NSW, only claims up to $10,000 can be made in civil cases.

If the matter is too serious for the lower courts, it is referred up to higher courts. Therefore serious cases sometimes start in the lower courts for committal hearings and then they are referred to higher courts. Decisions of the lower courts are made by a single judge.

The intermediate courts deal with more serious criminal offences such as rape for example and with more complex or expensive civil disputes. Civil cases are decided by a judge and jury of six, however parties can waive their right to a jury. Criminal cases are heard by a judge and a jury of twelve.

The Supreme Courts deal with major civil cases and serious criminal cases like murder. The Supreme Courts have a trial division and an appeal division. The appeal division hears appeals from the lower state courts and the trial divisions of the Supreme Courts.

2. The main Federal Courts are the:

- Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia[1]

- Federal Court of Australia

- High Court of Australia.

Federal judges and magistrates are appointed by the government of the day.

The Australian Constitution does not set out specific qualifications required by federal judges and magistrates. However, laws made by the Commonwealth Parliament provide that, to be appointed as a federal judge, a person must have been a legal practitioner for at least five years or be a judge of another court. To be appointed as a federal magistrate, a person must have been a legal practitioner for at least five years. To be appointed as a judge of the Family Court of Australia, a person must also be suitable to deal with family law matters by reason of training, experience and personality.

All federal judges and magistrates are appointed to the age of 70. The Australian Constitution provides that a federal judge or magistrate can only be removed from office on the ground of proved misbehaviour or incapacity, on an address from both the House of Representatives and the Senate in the same session. The Australian Constitution provides that the remuneration of a federal judge or magistrate cannot be reduced while the person holds office. These guarantees of tenure and remuneration assist in securing judicial independence.

3. The High Court

The High Court is also the final court of appeal within Australia in all other types of cases, including those dealing with purely State matters such as the interpretation of State criminal laws.

The Court has a Chief Justice and six other judges.

One of the High Court’s principal functions is to decide disputes about the meaning of the Constitution. For example, if the validity of an Act passed by the Commonwealth Parliament is challenged, the High Court is responsible for ultimately determining whether the Act is within the legislative powers of the Commonwealth.

The High Court has two types of jurisdiction: original and appellate.

Original jurisdiction is conferred by section 75 of the Constitution in respect of the following matters:

- matters arising under any treaty

- matters affecting consuls or other representatives of other countries

- matters in which the Commonwealth of Australia, or a person suing or being sued on behalf of the Commonwealth of Australia, is a party

- matters between States, or between residents of different States, or between a State and a resident of another State, and matters in which a writ of mandamus or prohibition – or an injunction is sought against an officer of the Commonwealth, including a judge.

If there is a dispute on whether federal elections were held properly or not, the High Court is able to hear these cases.

Section 73 of the Constitution confers appellate jurisdiction on the High Court to hear appeals from decisions of:

- the High Court in its original jurisdiction;

- Federal courts

- other courts exercising federal jurisdiction, and

- State Supreme Courts.

In considering whether to grant an application for leave to appeal from a judgment, the High Court may have regard to any matters that it considers relevant, but it is required to have regard to whether the application before it:

- involves a question of law that is of public importance, or upon which there are differences of opinion within, or among, different courts, or

- should be considered by the High Court in the interests of the administration of justice.

4. Circuit Courts

In regional and remote regions of Australia a visiting court system operates to provide court services across the continent. The visiting courts are known as Circuit Courts and they include a range of federal and state and territory courts. For example, the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia operates on circuit as do the intermediate or District courts and the Supreme courts. The Indigenous courts such as the Koori Court in Victoria also operate on circuit. While the hearing of courts such as the Supreme Court may be infrequent in regional and remote areas, it means that people in these regions have some access to court services in their area.

[1] In 2021, the Government introduced legislation merging the Family Court with the Federal Circuit Court of Australia to form the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia, effective from 1 September 2021.

2.11. Types of Legal Services

There are different types of legal service providers in our community. Some are run with private money like a business, such as a law firm or a lawyer in private practice. Others are funded by the State or Federal Government such as Community Legal Centres or Aboriginal Legal Services. These services are subjected to cyclical reviews and secure funding for fixed periods of time. There are also specialist government departments such as the Legal Aid Commission, the Crown Solicitor’s Office or the Department of Public Prosecutions that are funded by the relevant Government. Legal research is an essential part of the work done in all these organisations.

2.12. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Services

The Commonwealth government through the Attorney-General’s Department provides funding for Aboriginal legal services throughout Australia through its Indigenous Law and Justice branch.

Indigenous Legal Aid and Policy Law Reform[1]

The Department contracts the following Indigenous organisations to deliver legal aid services to Indigenous Australians in their state or zones:

The state and territory bodies include:

· NSW: Aboriginal Legal Service ACT/NSW http://www.alsnswact.org.au/;

· VIC: Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service http://vals.org.au/;

· Central Australia Aboriginal Legal Service http://www.caalas.com.au/;

· NT : North Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency http://www.naaja.org.au/;

· QLD : Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Service http://www.atsils.org.au/;

· SA : Aboriginal Legal Rights Movement http://www.alrm.org.au/;

· WA: Aboriginal Legal Service of Western Australia http://www.als.org.au/; and

· TAS: Aboriginal Legal Service http://tacinc.com.au/.

These are not-for-profit organisations that are community controlled with a community Board responsible for governance. They provide legal advice and representation in criminal, family, civil, and care and protection matters. They also provide other services including prisoner support, community legal education, advocacy and law reform. The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Services (NATSIL) (http://www.natsils.org.au/Home.aspx) is the over-arching, co-ordinating body for all these organisations (except Tasmania).

These organisations are generally funded to employ lawyers and administrative staff. Generally lawyers need to conduct their own research as there is not enough funding for research staff or legal clerks/paralegals. Some ALS’s have volunteer staff who assist them with their legal research.

Family Violence Prevention Legal Services[2]

The Australian Government, through the Attorney-General’s Department, provides funding for the Family Violence Prevention Legal Services (FVPLS) program. The program provides culturally sensitive assistance to Indigenous victim-survivors of family violence and sexual assault through the provision of legal assistance, court support, casework and counselling.

The FVPLS complements State and Territory initiatives. Funding from the Australian Government should be regarded as complementary and the Department encourages applicants to seek funding from other sources. All applicants will be required to provide information to the Australian Government Attorney-General's Department relating to funding received, and/or applied for, from other sources.

FVPLS delivers the following services:

- legal advice and casework assistance

- court support

- counselling to victims of sexual assault

- assistance and support to victims of sexual assault

- child protection and support

- information, support and referral services

- community engagement

- referrals

- law reform and advocacy

- early intervention and prevention, and

- community legal education.

NSW Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions

The NSW Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions (ODPP) is an independent prosecutorial body created in 1987. It is a government agency responsible for prosecuting criminal matters throughout NSW. All prosecutions must be conducted in accordance with the ODPP Prosecution Guidelines.[3]

ODPP staff includes lawyers and administrative support. The office deals with a range of criminal matters in including committal proceedings, appeals, and trial matters. Lawyers from this office appear in Local, Appeals, District, Appeal and Supreme Courts in NSW. The office also has a specialised Research Unit dedicated to legal research.

Private Practice

There are different types of private legal practices in our community. Lawyers (solicitors and barristers) who work in private practice effectively run a private business and are not dependent on government funding. They will employ lawyers and administrative staff. Private practices vary in size. There are sole practitioners, small, medium and large sized law firms. These lawyers may conduct their own research or they may employ legal clerks to assist them with their legal research.

[1] http://www.indigenousjustice.gov.au/db/projects/285862.html

[2] http://www.indigenousjustice.gov.au/db/projects/285864.html

[3] http://www.odpp.nsw.gov.au/prosecution-guidelines

2.13. Legal Research

Legal research is an important part of working in any type of legal organisation. Being able to efficiently and accurately identify legal information will enable you to assist your colleagues and your clients. Research skills are essential in doing the following type of work:

· finding information;

· increasing understanding about a topic;

· the provision of accurate legal advice to clients;

· developing a case strategy for litigation;

· for raising awareness community or legal education;

· policy reform; and

· advocacy work.

Research is an essential part of the work done at all types of legal organisations including private law firms, government (i.e. Legal Aid, Aboriginal Legal Services, Family Violence Prevention Legal Service or the Department of Public Prosecutions) or non-government organisations (i.e. Community Legal Centres). Each organisation will have its own processes, procedures and systems that you will need to follow when you are conducting research.

2.14. Requests for Information

Receiving a request to conduct some research

In the workplace you may be asked to do some legal research to identify some information. This information might be needed so that a lawyer can give a client legal advice, it might be used as part of the process of formulating a case strategy or for writing a law reform submission. It may simply be to find out some information about an organisation or contact details for somebody. Or you may be asked to research and identify different types of information, such as:

· what the law is on a particular issue;

· identifying some relevant case law;

· finding an article;

· locating financial information;

· collating some statistics;

· correspondence; or

· some international law.

A request for you to do some legal research may come from different people such as from a solicitor or barrister, internal or external staff, staff in another office or another party (your manager or Supervisor). You may receive this request electronically, paper based or verbally.

It is important to make sure you clearly understand what the task is and when it needs to be completed. It may be appropriate to acknowledge that you have received the request in accordance with office procedure. For example, if you received an email requesting you conduct some research, you would ordinarily reply to the email and confirm whether or not you can comply with the request, and the approximate timeframe.

Action the request for information

Once you have received a request to research and identify some legal information it is important that you process the request in line with your organisation’s procedures or recording system.

1. Ensure that you record the request for information such as by:

· Opening a file;

· Making a file note;

· Writing an internal memo; and/or

· Ensuring copies are on the file (hard copy and electronic).

2. Confirm client identity and needs.

If the request for information is from a client then it is important to make sure you get the information you need and do the appropriate checks before you start work. You will usually need to:

· Record the name, date of birth and address of the client.

· Record the details of other party (s).

· Clarify the needs and expectations of the client.

· You may need to discuss relevant criteria with your supervising lawyer or another colleague to ensure the client’s needs are met.

· Confidentiality / right to receive information.

· Conflict check.

3. Appropriate response and formatting

Make sure you are clear about how you are expected to respond to the request. Different workplaces will have different requirements for how they expect you to present your research findings. For example, do you need to:

· Prepare a file note?

· Draft an internal memo?

· Draft a letter of advice?

· Prepare a report?

Your organisation will usually have some pro forma documents that you can use to help you to complete your work in the correct format. There may be requirements about the appropriate use of photocopies and originals. In some cases you will also need to forward the request to another person as part of this process.

2.15. Identify Relevant Sources of Legal Information

Where to start your research? What sources of information do you need?

It is important to be aware that there is a large range of resources that can help you with your research. They may be online, in hard copy, at an organisation or with a person. Being aware of different sources of information will help you be able to identify which sources will help you to complete your research task.

Different Sources of Information

1) Relevant Sources of Information

In a legal environment there are a lot of different types of information that you may need to access. You may be asked to identify and research the following relevant sources of information:

· Legislation

· Case law

· Agreements

· Articles (journal, newspaper)

· Client files

· Court documents

· Affidavits

· Financial information

· Internal Correspondence

· Letters

· Media (audio, television, video)

· Precedents

· Statistics

· Transcripts

· Internet

· Organisations

· Specialists

There is a broad range of legal research tasks you may be asked to do. There is also a diverse range of relevant resources that you might need to access so that you can complete your research. Once you have identified the relevant sources of information you will need to identify exactly which document(s) or parts of document(s) you need.

You may need to:

· find a section in an Act;

· locate a quote from a judge in a case;

· collate some sentencing statistics; or

· you may need to summarise a case file and draft a chronology.

Every research task will be different so it is important to keep in mind exactly what the request is so that you can efficiently locate the relevant information.

2) Location of Information

Relevant sources of information may be available online or hard copy. Your sources may be in different locations such as in databases, search engines, the library, at the court registry or the client’s files. In many cases you will need to locate information from more than one source and more than one location.

3) Types of Information

Different types of information include:

· Agreements;

· Certificates;

· Correspondence;

· Journals,

· Court Documents;

· Organisational Reports;

· Medical Information;

· Statistics;

· Legislation; or

· Reports

Accessing Sources

Once you have worked out where you need to look for the information you will need to think about how you can get access to the particular resource. In some cases this might mean ensuring that you have a username and password to access a particular database such as LexisNexis or the Federal Register of Legislation. You may need to ask you client to fill in a Freedom of Information form so that you can make a request for some information from a government department that is otherwise protected by Copyright or Privacy Laws. You may need to comply with an internal office procedure to access a case file. You may need to write a letter to the court requesting a document.

It is important to make sure that you find out what procedures are in place for accessing the resource you need and that you take steps to resolve any issues as quickly as possible. For example, if you need a username and password you should ask you Supervisor who is the best person to ask to get this information. If you need to write to the court you should find out what proforma letter is used by your office to do this.

Obtaining Information

Once you have identified your information source and how you can access it the next step is to get the information so that you can use it in accordance with your request. Usually this will mean getting a copy of the resource. You may need to:

· Print out an entire document or

· Cut and paste sections of a document.

In some cases there may be a fee for obtaining a copy of a document. Often this is the case if you are requesting documents from a court. In some cases you can apply to have the fee waived.

Maintaining Confidentiality, Accuracy and Integrity of Information

Make sure you are aware of any organisational guidelines about security and confidentiality procedures that may relate to the information. This might apply to court dates, fees, health history or personal history. It is also important to also ensure the integrity of the document by making sure that you have a complete document, that all the pages are there and in the correct order and it is neat.

Have you completed your research task?

Once you have obtained a relevant source of information as part of your research it is important that you make sure it actually meets the need of the request. There are different things you can do to achieve this. Such as:

· You could look at the research request again and clarify exactly what is required and what your client’s needs are. You may then need to examine and analyse the information you have found to see if it is exactly what is needed.

· You may need to evaluate whether this resource completely addresses the request or if some additional research needs to be done. It may be that this source of information is only part of what you need and you need to do some additional research.

· In some cases you may need to edit or summarise the information.

· You may need to combine a number of resources together to adequately respond to the request. For example you may need to combine a section from an act, a paragraph from a precedent and a page from a current journal article.

Each case will be different so it is really important to be clear about what is needed, both in terms of the information request and the client’s needs.

Compiling your Research

Once you have completed the research you will need to present your findings in a particular format. In some cases you will need to prepare a report or some other type of correspondence such as an internal memo or a file note. Regardless of the format it is important that you accurately, clearly and concisely present your research findings. Thinking about the structure of your report can also be helpful at the beginning of your research as it can help you to clarify exactly what it is you are looking for.

Structure

Firstly identify what is the appropriate format for presenting your research findings. (This should have been made clear at the outset when the research request was made.) You will need to plan how you will structure and present your findings.

An example structure for an internal memo could be:

1) Research Task: To locate the relevant NSW law relating to High Range Drink Driving Offences, specifically relating to sentencing considerations.

2) NSW Legislation

3) Key Guideline judgment

4) Key circumstances identified in the guideline judgment that the court takes into account in sentencing

5) Relevant client circumstances

Another example:

1) Research Task: To prepare a chronology for a client’s family law case.

2) List key documents used (index)

3) Prepare a table with a brief summary of each document

4) Put copies all the documents in chronological order in a separate folder with dividers and an index, placing an index at the front.

Another example:

1) Research Task: Prepare a report summarising the law in all Australian jurisdictions on domestic violence law.

2) Synopsis

3) Introduction on domestic violence law

4) Chapter on the law each State and Territory

5) Conclusion/ Summary

People have different styles and often the research task itself will help you to structure your report. For longer documents it is useful to put a summary or synopsis at the beginning of the report or a summary table of your research findings.

Using Plain English and Editing

It is important to make sure that your research findings can be easily read and understood. This is particularly important if you are drafting work for someone who is not familiar with the law, such as a client. To do this you need to:

· Use clear and concise language.

· Use plain English.

· Use correct grammar and spelling.

· Proof read your work.

You may ask a colleague or Supervisor to read your work to ensure it is easily understood and conveys the meaning you intended.

Organisational Requirements

Each organisation will have its own requirements about formatting and procedures relating to reports and correspondence. Most organisations have requirements for the format of their documents such as:

· When to use letterhead.

· Correct line spacing, margins.

· Placing of headings.

· Use of cover sheets.

· Use of headers and footers.

You should make sure that the document conforms with the organisation’s policies and procedures. In some cases you can do this yourself, in other cases a colleague may be able to assist you with this. Some examples of an organisation’s policies and procedures are:

· Protocols for accommodating specific client needs such as using an interpreter or contacting a parole officer.

· Customer service protocols.

· Security, privacy and confidentiality procedures.

· Format of report or correspondence.

2.16. Finalising your research task

Review and Sign-off

At the beginning of your research it is really important to be mindful of the deadline for your work. There may also be a requirement within your organisation that a designated person will need to review and/or sign off on the report or correspondence. You will need to factor this into your planning so that you can meet the deadline. This requirement is likely to apply to a draft letter or report. This person may be your Supervisor or another person in the organisation.

Apply Organisational Requests

Each organisation will have its own information recording procedures. These procedures are essential for running an efficient and effective organisation/firm so that documents can easily and quickly be accessed. This means that each time you complete some research work it is important that you copy, file and record your research report/correspondence in line with the organisational requirements. For example, you may need to save a copy of the report to a file in a client folder and also make a hard copy and place it on the file in the filing cabinet. You may need to copy your report and put it in the office library and add it as a record in the library catalogue. An organisation’s information-recording procedures may also set out requirements for attaching a file name and case number; ensuring client details are up to date, and the storage and security of a copy.

Forward to Client

In cases where you have responded directly to a request from a client then you will need to write a letter of advice and send it to the client. It is important that you ensure it has been reviewed and complies with all organisational and professional requirements before sending it out.

2.17. Research Resources

Tranby Library

Some suggested introductory resources for this Block that are available at the Tranby library include:

Introductory general legal text

Carvan, J.(2009) Understanding the Australian Legal System, Law Book Co, Sydney.

Redfern Legal Centre Publishing (2009) The Law Handbook NSW, Redfern Legal Centre Publishing, Sydney

Saunders, Cheryl. (2003) It's your constitution : governing Australia today, Federation Press, Annandale, N.S.W.

Waller, L., Maher, FKH, & Derham, D., (1995) An introduction to the law (7th edition), LBC, Sydney.

Crawford, J & Opeskin, B., (2004) Australian Courts of Law, Oxford University Press, South Melbourne.

Introductory Indigenous legal texts

Behrendt, L., Cunneen, C., and Libesman T., (2009), Indigenous Legal Relations in Australia, Oxford University Press, Sydney

Stephenson, MA., and Ratnapala, S., (eds) (1993) Mabo: A Judicial Revolution: The Aboriginal Land Rights Decision and its Impact on Australian Law , St Lucia: University of Queensland Press.

Bennett, S., (1999) White Politics and Black Australians, Allen & Unwin, St Leonards, NSW.

Havemann, P., (Ed) (1999) Indigenous People’s Rights in Australia, Canada and New Zealand, Oxford University Press, Auckland.

Anthony, T., Beacroft, L., Brennan, S., Davis, M., Janke, T., McRae, H., Nettheim., G., (2009) Indigenous Legal Issues: Commentary and Materials (4th edition) LBC, Sydney.

Internet Resources

The internet is a valuable legal study resource. The following is a guide to some legal search engines and sites that students should consult during the course.

Legal databases – that have primary resources, such as legislation, cases and ancillary documents. Please see the following examples.

Austlii

· What is Austlii?

“The Australasian Legal Information Institute (AustLII) provides free internet access to Australian legal materials. AustLII's broad public policy agenda is to improve access to justice through better access to information. To that end, we have become one of the largest sources of legal materials on the net, with over seven gigabytes of raw text materials and over 1.5 million searchable documents.

AustLII publishes public legal information -- that is, primary legal materials (legislation, treaties and decisions of courts and tribunals); and secondary legal materials created by public bodies for purposes of public access (law reform and royal commission reports for example). You will find these materials listed under AustLII Databases.

AustLII maintains its own collections of primary materials: legislation and court judgements ("case law"). Some legal training or familiarity with the subject matter is sometimes required to make use of these documents.

Alternatively, AustLII also has a collection of secondary materials: commentaries and summaries on the law. This includes large projects such as the Reconciliation and Social Justice Library, the reports of the Australian Law Reform Commission and many others”.[1]

- Please see: www.austlii.edu.au

The Federal Register of Legislation

· What is the Federal Register of Legislation? Formerly known as ComLaw, the Federal Register of Legislation:

“… has the most complete and up-to-date collection of Commonwealth legislation and includes notices from the Commonwealth Government Notices Gazette from 1 October 2012”.[2]

- Please see: http://www.legislation.gov.au

Attorney General’s Department

· At this site you will find:

“ information on Australia's legal system and access to justice. Find out about legal aid and other assistance programs, contract and administrative law, native title, dispute resolution and the courts.”

· See: http://www.ag.gov.au/LegalSystem/Pages/default.aspx

3. Manage responsibilities in relation to law reform

This unit describes the performance outcomes, skills and knowledge required to monitor legislation that impacts Indigenous clients and organisations and to implement changes in workplace operations in response to legislative changes.

In Australia, law reform occurs in a variety of ways. For instance, legislation may be created, amended or repealed by the federal and state legislatures. Often these legislative changes reflect new societal values and needs. For example, development in internet technology has required the enactment of new laws to deal with the myriad of issues associated with internet use and social media. This type of law reform generally takes place over a long period of time. In contrast to this, law reform may also occur as a result of high profile incidents/events that receive widespread media coverage and result in public demand for government action. The Bikie laws, anti-terrorism laws and one-punch manslaughter laws are recent examples of such law reform. Unfortunately, this type of law reform is often a knee-jerk reaction of the government to public pressure. When the government rushes legislation through the legislature under such conditions, there is a significant risk the result will be bad law.

A further process of law reform in Australia is that which occurs through the Common Law. Changes in the law brought about through major decisions of Judges are less predictable and less able to be controlled than legislative reform. However, often governments will introduce new legislation or amend existing legislation in response to important court decisions which touch on matters of public interest. The decision of the Australian High Court in Mabo v Queensland (No 2)[1992][1] and the subsequent enactment of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) is such an example.

For the most part, law reform is the result of extensive political discourse on issues that are taken up on the State and/or Federal Government’s policy agenda. Political debate over law reform is influenced heavily by the media, public perception, lobby groups and Law Reform Commissions (both national and state).[2] Law reform is often heavily politicised and has much to do with the balance of political power in the State and Federal governments at any given time. The introduction of mandatory sentencing for certain offences, or the excising of parts of Australia for the purpose of processing asylum-seekers, are examples of the legislature changing the law to accord with political values.

Throughout this unit you will learn about the structure and function of Law Reform Commissions. Law Reform Commissions exist at a national and state/territory level. They are important bodies which assist the law reform process by carrying out research, undertaking consultation with relevant stakeholders and writing reports. Importantly, these reports consider the appropriateness of the current legal framework and put forward recommendations to the government on how to enhance this framework.

Understanding law reform processes and developing the skills to participate in these processes is empowering and an important step towards effecting important changes.

[1]Mabo v Queensland (No 2) [1992] HCA 23; (1992) 175 CLR 1 (3 June 1992)

[2] In NSW, the equivalent is NSW Law Reform Commission

3.1. The Law Reform Process

The Australian Government identifies an area of Commonwealth law that needs to be updated, improved or developed for various reasons i.e. public concern

The ALRC (Australian Law Reform Commission) conducts research with ‘stakeholders’

(these may include government departments, courts, legal professionals, industry groups, non-government organisations, special interest groups etc.)

An Issues Paper and/or Discussion Paper is made

The ALRC makes a formal call for submissions whenever it releases an Issues Paper or Discussion Paper

(Through the submissions it receives, the ALRC can gauge what people think about current laws, how they should be changed and can test its proposals for reform)

Each inquiry culminates in the production of a Final Report. The Final Report must be delivered to the Attorney-General by the date specified in the Terms of Reference. The recommendations in the Final Report describe the key reforms that the ALRC considers should be made either to laws or legal processes

The Attorney-General is required to table the Final Report in Parliament within 15 sitting days of receiving it, after which it can be made available to the public

The Australian Government decides whether to implement the recommendations, in whole or in part

No set time frame in which the Government is required to respond

Implementation of ALRC recommendations is tracked and recorded each year in the ALRC’s Annual Report

What are the implications of law reform?[1]

Law reform seeks to:

- simplify and modernise the law;

- improve access to justice;

- remove obsolete or unnecessary laws;

- eliminate defects in the law;

- suggest new or more effective methods for administering the law and dispensing justice;

- ensure harmonisation of Commonwealth, state and territory laws where possible;

- monitor overseas legal systems to ensure Australia compares favourably with international best practice;

- alter out-dated or misguided societal values on a bureaucratic level.

Law Reform Commissions[2]

Law reform is a collaborative process. Law Reform Commissions conduct intensive research in order to identify key societal issues or possible areas for reform. This research relies heavily on academic literature and empirical studies. Commissions engage with stakeholders and industry experts through extensive consultation. Commissions then discuss their preliminary ideas for reform in consultation papers or question papers.[3]

Anyone can make a submission to the ALRC on a reference. Any public contribution to an inquiry is called a submission and is crucial in assisting the ALRC to develop its proposals for law reform. Submissions are addressed to ‘Response to a Discussion Paper’. There is no set format for submissions; they may be online or written. For each inquiry, once a consultation paper has been released, the ALRC develops an online submission form designed to help stakeholders address the specific questions or topics.[4]

When attempting to engage in policy development or reform and improve the legal system as an individual or as part of a lobby group, keep in mind:

- being informed about the issue is crucial; the most effective submissions are well researched;

- qualitative research and statistical evidence are particularly persuasive;

- drafting is a crucial process for accuracy and comprehensiveness;

- structuring the submission with headings and subheadings will ensure it is easy to follow;

- gaining the support of, or teaming up with, appropriate influential entities can strengthen your position;

- suggesting change is necessary is not always sufficient, providing realistic possibilities for reform is more effective;

- the proposal may not necessarily be welcomed by all members of the public, therefore persistence and passion are key if you believe your proposed reform will be of great benefit.[5]

The Australian Law Reform Commission (‘ALRC’)

Established in 1975, the ALRC is a permanent, independent federal statutory corporation, operating under the Australian Law Reform Commission Act 1996 (Cth). The ALRC conducts inquiries - known as references - into areas of law reform at the request of the Attorney-General of Australia.

While accountable to the federal Parliament for its budget and activities, the ALRC is not under the control of government, giving it the intellectual independence and ability to make research findings and recommendations without fear or favour.

Although ALRC recommendations inform government decisions on law reform, they do not automatically become law. However, the ALRC has a strong record of its advice being followed. Nearly 80 per cent of the ALRC's reports have been either substantially or partially implemented - making it one of the most influential agents for legal reform in Australia[6].

The ALRC's focus is on federal laws and legal processes. The ALRC must always ensure that the laws it reviews are consistent with Australia's international obligations to uphold the civil liberties and human rights of its people.

State & Territory Law Reform Commissions[7]

Law reform commissions also operate within each state and territory. These commissions review the laws applicable to their respective jurisdictions and seek to meet the specific needs of the people residing in that state or territory. These organisations are also independent statutory bodies.

State based law reform commissions provide legal policy advice to Government on issues that are referred to the commission by the Attorney General (called “references”). They prepare reports which comprehensively analyse the issues identified in the reference and make recommendations to Government for legislative reform. State law reform commissions also receive, analyse and present submissions from stakeholders and interested members of the public. A project is completed when a final report is tabled in Parliament and made public on their website.

Case study: Shopfront Youth Legal Centre

Shop Front Youth Legal Centre is a legal service provider for people aged 25 years and under who are homeless or disadvantaged. The community legal centre is also involved in making submissions to government and parliamentary enquiries in an effort to improve laws and policies, particularly those affecting the youth or disadvantaged.[8]

An example of a submission collated by The Shop Front Youth Legal Centre in January 2014 can be viewed at the following website… http://www.theshopfront.org/documents/Parole_-_submission_on_QP_6.pdf. This particular submission was prepared in response to a discussion paper on parole, more specifically, Question Paper 6: Parole for young offenders. Each question is responded to in a clear and succinct manner, with realistic suggestions made for appropriate reform. The authors of this paper have sought to emphasise how the juvenile justice system recognises that young offenders are not “little adults”. Rather that they require different treatment, as made clear in our international obligations under the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and the Beijing Rules.[9]

[1] Australian Law Reform Commission, (2014), ‘About’, <http://www.alrc.gov.au/about>, Accessed 8 January 2015.

[2] Australian Law Reform Commission, (2014), ‘About’, <http://www.alrc.gov.au/about>, Accessed 8 January 2015.

[3] Cox, E, (2010), What is Policy? Centre for Policy Development, Available online at: http://youthscape.vibewire.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/07/whatispolicy.pdf

[4] Australian Law Reform Commission, (2014), ‘Making a submission’, <http://www.alrc.gov.au/about/making-submission>, Accessed 9 January 2015.

[5] Cox, E, (2010), What is Policy? Centre for Policy Development, Available online at: http://youthscape.vibewire.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/07/whatispolicy.pdf

[6]ALRC Annual Report at http://issuu.com/alrc/docs/annual_report_2014_d10243aecd383c?e=1402665/9789434 [accessed 13/01/2015]

[7] Law Reform Commission, (2013), ‘What we do’, < http://www.lawreform.justice.ns w.gov.au/lrc/lrc_whatwedo.html>, Accessed 8 January 2015.

[8] The Shopfront Youth Legal Centre, (n.d.), ‘Policy submissions and papers’, <http://www.theshopfront.org/25.html> Accessed 9 January 2015.

[9] The Shopfront Youth Legal Centre, (2014), Parole: Question Paper 6: Parole for young offenders

Submission from the Shopfront Youth Legal Centre, Available online at: http://www.theshopfront.org/documents/Parole_-_submission_on_QP_6.pdf.

3.2. Parliamentary Law Reform

Parliamentary Committees[1]

One of the formal ways law reform can be undertaken is by making a submission to a parliamentary committee (the Commonwealth, states and territories all have similar processes). The role of a parliamentary committee is to examine a legal issue and/or proposed law by holding public inquiries that receive written submissions and oral evidence from members of the public, organisations and experts.

What is a Parliamentary Committee?

A Parliamentary Committee is a group of Members of Parliament, appointed by the Parliament, to investigate policy issues, proposed legislation or government activities. The membership of these Committees tends to reflect the diverse political make-up of the House (Upper or Lower) from which they are drawn. The work of Parliament has become more complex. Members have to consider an increasing range of issues and legislation. At the same time more people in the community want to participate in the democratic process. Committees allow Parliamentarians to examine an issue in more detail and with greater public input than if either House as a whole considered the matter.

Parliamentary Committees provide an opportunity for individuals and groups to put their views directly to Parliamentarians. Members of the public can:

- make submissions

- give oral evidence

- attend public hearings, and

Parliamentary Inquiries

In most cases, one of the Houses or a Minister refers inquiries to a Committee. The terms of reference define the scope of an inquiry and are determined by the House or the Minister responsible for referring the inquiry.

A committee will often start its inquiry by calling for submissions from the public and relevant organisations. The inquiry's terms of reference are usually advertised in the appropriate newspapers and are published on this Internet site. These should be followed by people making a submission. Anyone can make a submission but people or organisations with specialist knowledge or representative views may be invited to make a submission.

After the committee has examined all the submissions, witnesses may be invited to give oral evidence. This allows committee members to speak directly to people about matters relevant to an inquiry and seek clarification or further details about issues raised in a submission. Members of the public may observe these hearings, although sometimes they occur in private.

In addition to calling for submissions and taking evidence, committees may canvass public opinion on the issues raised by an inquiry in a number of other ways. These include seminars, conferences, study tours, workshops and round-table discussions.

Committee Reports

After considering all the submissions, evidence and its own research, the committee produces a report. This is tabled in the House that initiated the inquiry and includes the committee's findings and recommendations. The tabling of a report provides an opportunity for all members of the House to debate the findings. The committee's formal involvement in an issue effectively ends with the tabling of its report.