M3: Learner Manual

| Site: | Tranby National Indigenous Adult Education & Training |

| Course: | BSB41021 Certificate IV in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Governance 2025 |

| Book: | M3: Learner Manual |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Saturday, 28 February 2026, 8:23 AM |

Table of contents

- 1. Module 3: Finances & The Constitution of an Organisation

- 2. The Constitution of an Organisation

- 3. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Corporations

- 4. Review Current Organisational Activities and the Constitution

- 5. Cultural Context of Governance and Constitutions

- 6. Sample Constitutions

- 7. Interpreting Financial Reports

- 8. Legal Requirements for Financial Management of Organisations

- 9. Financial Policies and Procedures for Organisations

1. Module 3: Finances & The Constitution of an Organisation

Introduction

Module 3 includes two units of competency:

BSBFNG405 Review and apply the constitution in an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisation

This unit describes the skills and knowledge required to ensure that the constitution of an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisation is relevant, that it is understood by staff, and that it meets the organisation’s changing needs.

The unit applies to individuals who are board members, or in a governance role, and responsible for monitoring, guiding and undertaking decision-making activities of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations.

LGACOR011 Analyse financial reports and budgets

This unit describes the performance outcomes, skills and knowledge required to analyse financial reports and budgets.

This unit applies to individuals working in local government or other organisations who undertake financial governance activities.

The skills in this unit must be applied in accordance with Commonwealth and State or Territory legislation, Australian standards and industry codes of practice.

Clicking the links below will download Pdf versions of the Learner Manuals for this Module. This means you can download and access them offline. Alternatively, navigate through the menu on the right to read through the Learner Manual online.

2. The Constitution of an Organisation

Introduction

This Learner Manual addresses the Unit of Competency BSBFNG405 Review and apply the constitution in an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisation.

The Learning Objectives are:

· Describe the purpose of the constitution of an organisation.

· Summarise the legal requirements for a constitution of an organisation.

· Summarise the process of changing a Constitution

· Distinguish between Indigenous governance and organisational governance.

The Constitution of an Organisation

A Constitution is a legal set of rules by which organisations operate. Board members exercise powers in accordance with the corporation’s Constitution The Constitution is sometimes referred to as the Rule Book.

An organisation needs to make decisions on the rules that will govern the running of the organisation. This way, it is clear to members and to any individuals and other organisations that it does business with, exactly what the organisation does, who owns its assets and who is responsible for making legal decisions on behalf of the organisation.

When these rules are determined and written down the document is known as the constitution of the organisation. The constitution should be readily available to members and other interested parties.

It is important that members and office bearers are familiar with the constitution or ‘the rules’ of an incorporated organisation.

Every new member should be provided with access to (or their own copy) of the constitution and the organisation needs to ensure that new members understand the constitution and that being a member means abiding by the rules it contains.

2.1. Legal Requirements for a Constitution

The following examples of organisations that may have a Constitution, may have different requirements according to the type of incorporation.

Company

A company’s internal management may be governed by:

· Provisions of the Corporations Act 2001 that apply to the company - known as replaceable rules.

· A constitution, or

· A combination of both.

The constitution is a contract between:

· The company and each member.

· The company and each director.

· The company and the company secretary, and

· A member and each other member.

A company can adopt a constitution before or after registration. If it is adopted before registration, each member must agree (in writing) to the terms of the Constitution If a constitution is adopted after registration, the company must pass a special resolution to adopt the Constitution[1]

Changing a Company Constitution

A company can change or repeal its constitution by passing a special resolution. A special resolution needs at least 28 days’ notice for publicly listed companies and 21 days’ notice for other company types. For the resolution to pass, at least 75% of the votes cast must be in favour.[2]

Associations in NSW

Every incorporated association must have a Constitution This can be the Model constitution or the association’s own constitution, which is recorded in the public register of incorporated associations, maintained by NSW Fair Trading.

The constitution must address each of the matters referred to in Schedule 1 of the Associations Incorporation Act 2009 (the Act), as follows:

· Membership qualifications: The requirements, if any, to become a member.

· Register of members: The register of the association’s members including fees, subscriptions etc. Any entrance fees, subscriptions and other amounts, if any, to be paid by the members.

· Members liabilities: A member’s liability, if any, towards the debts and liabilities of the association.

· Disciplining of members: The procedure, if any, for disciplining members, including an appeals process.

· Internal disputes: The procedure for the resolution of disputes between members and between members and the association.

· Committee: The composition, functions and processes of the committee, including:

o The election or appointment of the committee members.

o The terms of office of the committee members.

o The maximum number of consecutive terms of office of any office-bearers on the committee.

o The circumstances in which a committee member has to vacate office.

o The filling of casual vacancies on the committee, and

o The quorum (minimum number of members required at a meeting) and procedures to be followed at committee meetings.

· Calling of general meetings: The procedure for calling and holding a general meeting and the intervals between meetings.

· Notice of general meetings: The process for notifying members of a general meeting and notices of motion.

· Procedure at general meetings: The quorum, procedure and requirements for conducting a general meeting, and whether members are entitled to vote by proxy.

· Postal or electronic ballots: The types of resolutions that may be voted on by a postal or electronic ballot.

· Sources of funds: The sources of the association’s income.

· Management of funds: How the association's funds are to be managed and the procedure for drawing and signing cheques on behalf of the association.

· Custody of books etc: Who is responsible for the association's books, documents and securities.

· Inspection of books etc: The procedures for the inspection of books and documents by members.

· Financial year: The association's financial year.

· Winding up: The winding up of the association.

A representative of the association must certify that the constitution complies with the requirements of the Act, including the above matters, when registering the association and when registering changes to the Constitution[3]

Changing an Association’s Constitution

An association may change its constitution by passing a special resolution. The change must be consistent with the Act and the rest of the Constitution[1]

Co-operatives in NSW

A co-operative’s rules must provide for the matters included in Schedule 1 of the Co-operative National Law (CNL). The rules may contain other provisions appropriate for an individual co-operative as long as those provisions are not contrary to the co-operatives legislation.

A co-operative can adopt its own rules or the model rules. A co-operative can include some or all of the relevant model rules in its own rules.

Co-operatives should carefully consider its proposed rules to ensure they suit their operations and meet the requirements of Schedule 1.

Active membership provisions

The co-operative’s rules must include active membership provisions. These set out the co-operative’s primary activity/activities and what a member has to do to be an active member.

A co-operative’s primary activity is:

- Either by itself or together with another activity, the basic purpose for which the co-operative exists.

- Makes a significant contribution to the business of the co-operative, i.e. It contributes at least 10% to the turnover, income, expenses, surplus or business of the co-operative.

Members of a co-operative must satisfy the active membership requirements in the co-operative’s rules in order to be entitled to vote and to retain their membership. The active membership requirements must:

- Be reasonable when considered in relation to the activities of the co-operative as a whole.

- Be clear, repetitive and measurable, and

- Clearly define the period in which a member is required to use or support an activity or to maintain a relationship with the co-operative. For example, members must undertake specified obligations each financial or calendar year.

For non-distributing co-operatives an obligation to pay a regular subscription to be applied to a primary activity of the co-operative is sufficient to establish active membership of the co-operative.

For distributing co-operatives, the active membership provisions must require a member to use an activity of the co-operative for carrying on a primary activity together with any other provisions approved by the Registrar.

A co-operative must keep records to enable it to identify which of its members are active.

Changing a Co-operative's Constitution

In most cases a co-operative can only amend its rules or adopt new rules by passing a special resolution with a two-thirds majority (or a higher majority if required in the co-operative’s rules).

In very limited circumstances a board of a co-operative may pass a resolution amending the rules. This may only occur where an amendment is giving effect to a requirement, direction, restriction or prohibition imposed or given under the CNL.[2]

[1] https://asic.gov.au/for-business/registering-a-company/steps-to-register-a-company/constitution-and-replaceable-rules/

3. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Corporations

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups can incorporate under the Corporations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) Act 2006 (CATSI Act). As a corporation, they must create and abide by a constitution (the rule book).

An Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander corporation must have a written constitution, which at a minimum:

· Sets out the corporation’s name and objectives.

· Sets out a dispute resolution mechanism for disputes internal to the corporation.

The constitution may also:

· Modify or replace some or all of the ‘replaceable rules’, and/or

· Add other rules, provided they are workable and consistent with the Act

· Change the way some of the set laws work for the corporation.

The corporation’s constitution is effectively a contract:

· Between the corporation and each member.

· Between the corporation and each director and corporation secretary.

· Between a member and each other member.

Replaceable rules

The CATSI Act adopts a framework of rules that can be replaced similar to the Corporations Act 2001. These rules can be adopted as is or replaced with a rule that better suits the corporation’s own needs and circumstances. The replaced rule cannot simply state that the replaceable rule does not apply—it must cover the subject matter of that rule.

They allow corporations to adopt good governance procedures or tailor their rule book to their particular circumstances.

Set laws

The set laws apply to all corporations and cannot be changed like a replaceable rule because they are part of the CATSI Act. They cover things that are essential for ensuring good governance, such as members being able to ask directors to call a general meeting.

Optional rules

Corporations can create extra rules that suit their circumstances, as long as they comply with the CATSI Act.

Changing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Corporations Constitution

For the corporation to change its constitution, the following steps must be complied with:

· The corporation must pass a special resolution effecting the change.

· If, under the corporation’s constitution, there are further steps that must also be complied with to make a change, those steps must be complied with

o The corporation must lodge certain documents under rule 20.2.

o The registrar must make certain decisions in respect of the change and, if appropriate, must register the change[1]

4. Review Current Organisational Activities and the Constitution

It’s good business practice to review your rule book regularly and before your AGM is ideal. This is because if you want to make changes to your rules, they must be approved by members passing a special resolution. (A special resolution is passed when 75 per cent of the members present and voting at the AGM agree to the proposal.)

|

Preparation of various aspects of organisational activities and the Constitution will require planned timeframes. There needs to be sufficient lead time for consulting with external expert advisors and approvals, well in advance of an AGM. |

Over time your corporation naturally evolves which means your business activities and how you run them can change too. This is also an opportunity to review staff position descriptions so that they align with organisational goals and the Constitution

Rule books should be updated to:

· Say what the corporation does. The objectives in your rule book need to reflect the business of your corporation.

· Set out how your corporation is to be run. If your rule book sets out certain requirements you must follow them, even if they’re out of date. This is why it’s so important that your rule book keeps in step with the way your corporation wants to work, the requirements of members and directors, and how decisions are made.

Some rule books have been around for a long time. Corporations set their rules when they first register. Some still have the Registrar-initiated rule book from when they transitioned from the old Aboriginal Councils and Associations Act 1976 to the Corporations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) Act 2006. Those rule books are probably now out of date.

Some reasons for making changes to your rule book are to:

· Improve the way the corporation is run, how decisions are made, or the process for electing directors.

· Add new activities into the corporation’s objectives.

· Open up membership to another language group or geographical area.

· Add the use of technology to hold directors’ and members’ meetings (e.g. Teleconference) or distribution of documents to members by email.

· Make the rules easier to read and understand.

· Fix a minor error or problem that was missed the last time the rules were updated.[1]

4.1. Community Consultation

Proposed changes to the constitution should be communicated to the community through a process of consultation. It is vital that this consultation is done appropriately and with the right community members, especially including Elders. for it to be successful. Consultation may include repeated visits to communities. Proposed changes to the constitution need to be explained to the community, along with the possible effects they may have. Community members should be given time to consider the proposed change and have an opportunity to respond with questions and feedback.

4.2. Funding Body Requirements

Many corporations registered under the Corporations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) Act 2006 (the CATSI Act) receive funding from state and territory governments and Commonwealth government agencies. The CATSI Act makes a number of improvements that are relevant to funding bodies—such as encouraging better governed and more sustainable corporations and providing for improved risk management by funding bodies and corporations.

Under the CATSI Act funding bodies and creditors are better able to protect assets through strengthened rights as an interested party. For example, corporations and creditors can use the external administration provisions of the Corporations Act:

· voluntary administration

· receiver and liquidator provisions

· applications to a court to seek an order to protect assets[1]

4.3. Review Activities of the Board in relation to the Constitution

It is good business practice to review the implementation of the constitution regularly and before your AGM is ideal. These review processes require appropriate lead time to ensure they are completed in time for the AGM.

Matters to be reviewed would include:

· Elections.

· Membership.

· Conduct of meetings.

· Reporting.

4.4. Seeking Legal Support and Advice when Needed

Organisations, whether on the initiative of management or by board resolution, often take external professional or consultancy advice on matters under consideration by the organisation and/or its board. This can include legal, accounting and financial advice. The advice may be for the benefit of the organisation generally, or even only for the benefit of the board discretely from management; for example, in the performance of its oversight role of management, the board may need advice independent of any affiliation with management.

In terms of seeking external professional advice, the following good governance practice is recognised:

· On occasions, the entire board may wish to obtain external professional advice separately from the organisation on matters relating to their duties and responsibilities as a director(s);

· On other occasions, an individual director or a subset of directors may wish to obtain external professional advice separately from the organisation and the board on matters relating to their duties and responsibilities as a director(s);

· Provided they are acting in good faith, it is reasonable for them to do so at the expense of the organisation and accordingly.

o They should be entitled to reimbursement of expenses for the external professional advice taken.

o They should not risk breaching confidentiality obligations owed to the organisation by taking that advice.

· In such a case, an authority to do so should be given in accordance with applicable policies and procedures.

· Commonly, such an authority is found in one or more of the following instruments which have contractual status between the organisation and the director:

o Organisation’s constitution;

o Organisation’s governance or board charter;

o Letter of appointment by which the director was appointed to office;

o Deed of access, indemnity and insurance between the organisation and the director.[1]

4.5. Confirm Formal Documentation of Changes

If the registering body is ORIC:

If there is no extra requirement, within 28 days after the special resolution is passed, the corporation must lodge with the Registrar:

· A copy of the special resolution.

· A copy of those parts of the minutes of the meeting that relate to the passing of the special resolution.

o a directors’ statement signed by:

§ 2 directors or

§ if there is only 1 director, that director, to the effect that the special resolution was passed in accordance with the Act and the corporation’s constitution, and a copy of the constitutional change.

Other people who need to be notified would include:

· The community.

· Staff.

· Organisational members.

· The Board members.

Confirm the requirements for the way this information is communicated to the parties.

5. Cultural Context of Governance and Constitutions

Effective self-governance means not only having genuine decision-making power, but also being able to practically exercise that authority and take the responsibility for it (i.e. being accountable).

To exercise power effectively and legitimately, people need agreed rules and ways of enforcing them. Rules are the organising tools of governance. They tell us:

- How to behave towards each other and what to expect when we don’t.

- How power is shared.

- Who has the authority to make the important decisions.

- How decisions should be enforced.

- How the people who make decisions will be held accountable.

Governance rules can be the unwritten laws, traditions and ways of behaving that people live by. They can also be written down in documents such as constitutions, by-laws, policies, regulations, business and strategic plans, and company rules.

If your governing rules are poorly understood, easily sabotaged by selfish interests or erratically enforced, the legitimacy of your governing power and authority will be severely undermined.

The Indigenous Community Governance Research Project in Australia has identified several basic conditions which, in combination, help to produce effective Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander governance:

- Governing institutions (rules).

- Leadership.

- Genuine decision-making power.

- Practical capacity.

- Cultural legitimacy.

- Resources.

- Accountability.

- Participation.

Not surprisingly, to be effective and legitimate, these governance solutions need to be tailored to suit the local environment.

For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, achieving effective and legitimate governance can be particularly challenging because it involves working across Indigenous and western ways of governing, and trying to negotiate the demands of both.

5.1. Indigenous Governance

Culture is at the heart of every society’s governance arrangements and this is also true for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

For Indigenous governance to be effective it is not enough to simply cherry pick and import foreign governance structures and processes into communities and expect those communities to function effectively within those arrangements.

To be meaningful to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, the component parts of governance must reflect important relationships, networks and values.

The challenge is to craft arrangements that incorporate both the Indigenous requirement for cultural legitimacy, as well as meeting the governance requirements of the wider non-Indigenous society.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have always had their own governance. It is an ancient jurisdiction made up of a system of cultural geographies (‘country’), culture-based laws, traditions, rules, values, processes and structures that has been effective for tens of thousands of years, and which nations, clans and families continue to adapt and use to collectively organise themselves to achieve the things that are important to them.

As Mick Gooda, the Indigenous Social Justice Commissioner (2019) said:

“While Indigenous peoples have governed ourselves since time immemorial in accordance with our traditional laws and customs, when we speak of Indigenous governance we are not referring to the pre-colonial state. Rather, we are referring to contemporary Indigenous governance: the more recent melding of our traditional governance with the requirement to effectively respond to the wider governance environment.”

In many parts of Australia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander governance systems were disrupted and changed because of British colonisation. Often people were forcibly relocated to settlements that were run according to western governance structures, rules and values.

Today, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have many forms of governance based on their diverse histories, environments and cultures.

Indigenous governance is not the same thing as organisational governance. While governance is a critical part of the operation and effectiveness of legally formalised and registered incorporated organisations, it can also be seen at work every day:

- In the way people own and care for their country, arrange a ceremony, manage and share their resources, and pass on their knowledge.

- In networks of extended families who have a form of internal governance.

- In the way people arrange a community football match or an art festival, informally coordinate the activities of a night patrol and develop alliances across regions.

- In the voluntary work of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men and women within their own communities, and as governing members on a multitude of informal local committees and advisory groups.

What makes it Indigenous governance is the role that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social and philosophical systems, cultural values, traditions, rules and beliefs play in the governance of:

- Processes—how things are done.

- Structures—the ways people organise themselves and relate to each other.

- Institutions—the rules for how things should be done.

In other words, just like all other societies around the world, the practice of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander governance cannot be separated from its traditions and culture.

Today, many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are working to rebuild and strengthen their contemporary governance arrangements. The challenge in doing this is to ensure that governance solutions continue to reflect cultural norms, values and traditions, while remaining practically effective.[1]

5.2. The Importance of Indigenous Governance

Indigenous Governance is grounded in thousands of years of cultural continuity, community responsibility, and collective decision-making. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, governance is not just a structure or process—it is a living practice shaped by Lore, Country, kinship, and cultural authority. Effective governance ensures that decisions are made in ways that respect the past, reflect the present and protect the future of our communities.

Decision-Making Guided by Community, Lore and Cultural Authority

Our governance systems reflect a deep responsibility to Country and to each other. Decisions are not made for individual benefit, they arise from collective needs, community priorities and cultural practices that have sustained our people since time immemorial.

In Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander contexts:

· Lore guides what is right, responsible and respectful.

· Hierarchy and cultural roles define who holds authority to speak, decide and lead.

· Community needs shape the direction and priorities of our organisations.

This ensures decisions are culturally safe, ethically grounded and accountable to the people they affect.

Welcome to Country and Acknowledgment of Country

Welcome to Country and Acknowledgment of Country are essential cultural governance practices.

Welcome to Country

A Welcome to Country can only be performed by Elders or Traditional Custodians of the land on which the event takes place. For First Nations people, being Welcomed to Country is essential for our spirit, when entering another person’s Country. This practice:

· Recognises the unbroken connection of First Nations peoples to their Country.

· Demonstrates respect for the cultural sovereignty that exists regardless of colonisation.

· Reinforces the importance of authority, kinship and protocol within Indigenous governance.

Acknowledgment of Country

An Acknowledgment of Country is a governance responsibility for non-Custodians and guests. When done correctly this will:

· Acknowledge the Traditional Custodians and their Lore.

· Demonstrate awareness of whose Country people are gathering on.

· Maintain a respectful relationship with the local community and Elders.

These practices ensure cultural safety, integrity and accountability.

Language Groups, Borders and the Aboriginal Landscape

Country is not just land—it is our identity, ancestry, law and story systems. Each language group has distinct borders, responsibilities and connections to place.

In governance terms:

· Respecting language groups and boundaries ensures we honour the cultural authority of Traditional Custodians.

· Decisions about programs, events or services must reflect who has the cultural right to speak for that land.

· Understanding the Aboriginal cultural landscape helps organisations avoid cultural harm, strengthen relationships and operate with integrity.

Country governs us—we do not govern over Country.

Respect for Elders and the Role of Cultural Leadership

Elders are central to Indigenous governance structures. They hold cultural knowledge, lived experience and the authority to guide decision-making. Their involvement ensures:

· Cultural protocol is upheld.

· Decisions align with Lore and community expectations.

· Younger leaders learn respectfully and are supported in their growth.

In Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander governance, Elders provide stability, accountability and cultural legitimacy.

Growing Our Future Leaders – Youth Perspectives in Governance

Strong Indigenous governance prioritises the development of young people as future custodians, decision-makers and cultural knowledge holders. This includes:

· Creating governance spaces where youth voices are heard and valued.

· Passing on knowledge, skills and cultural responsibilities through mentoring, education, and community involvement.

· Ensuring governance structures reflect intergenerational leadership, not just senior leadership.

Our young people are inheritors of our Lore, our Country and our future—they must be equipped, included and empowered.

Indigenous governance is not simply a modern organisational framework - it is a continuation of ancient systems of making decisions, caring for Country, respecting Elders and protecting community. Whether through Welcome to Country protocols, acknowledging Custodianship, respecting language boundaries or nurturing future leaders - governance remains deeply tied to who we are as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Strong governance ensures that our communities thrive, our cultures remain strong and our responsibilities to Country and each other continue into future generations.

6. Sample Constitutions

Department of Fair Trading NSW Model Constitution for Associations:

Department of Fair Trading NSW Model Constitution for Co-operatives:

ORIC Rule Book Templates for Indigenous Corporations under the CATSI Act:

https://www.oric.gov.au/free-templates/rule-book-templates

Tranby Aboriginal Co-operative Constitution:

https://tranby.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/211216-Tranby-Rules-with-amendments.pdf

Constitution Template for Companies:

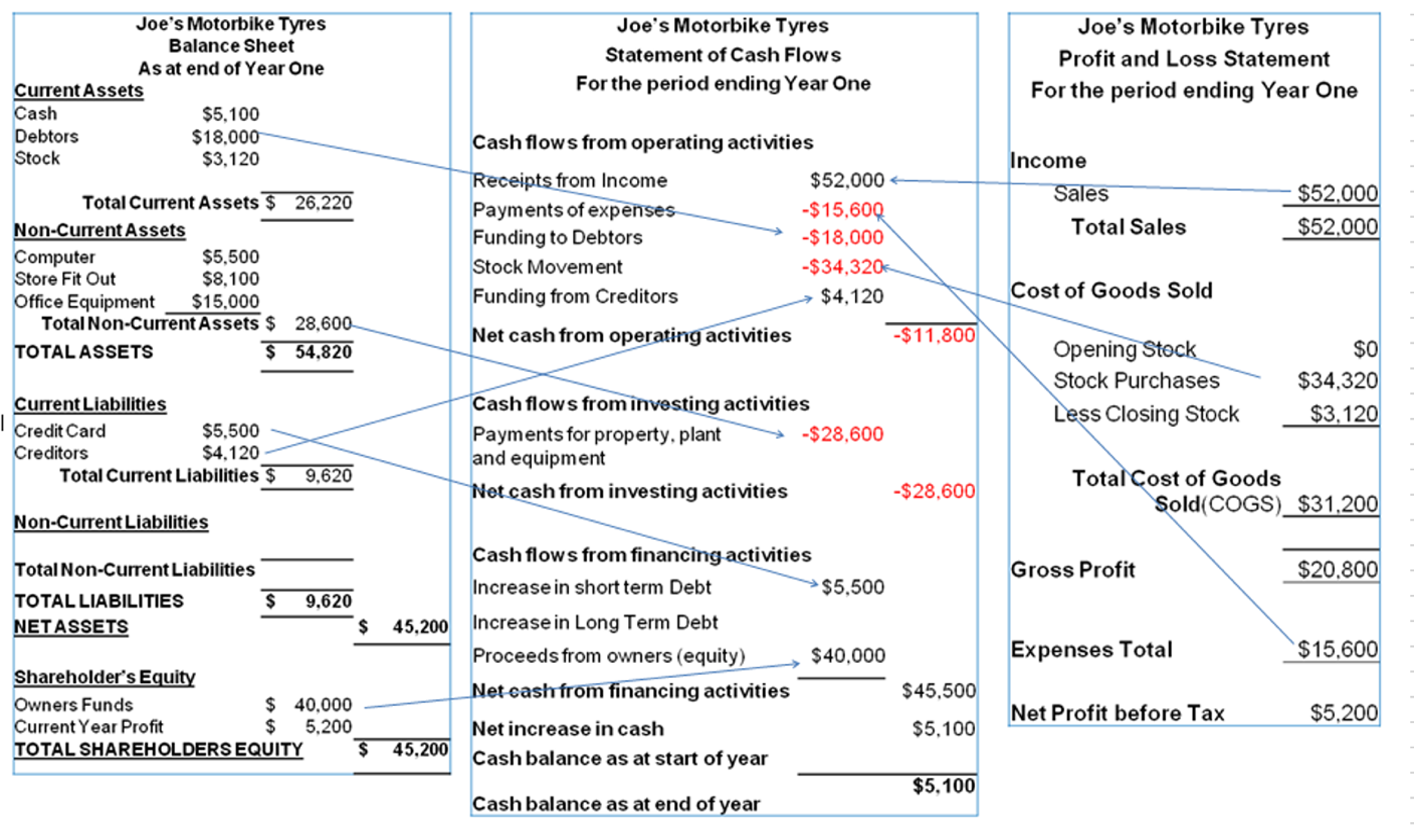

7. Interpreting Financial Reports

Introduction

This Learner Manual addresses the Unit of Competency LGACOR011 Analyse financial reports and budgets.

The Learning Objectives are:

· Summarise the purpose of a Profit and Loss Statement.

· Summarise the purpose of a Balance Sheet.

· Summarise the purpose of a Cash Flow Statement.

· Summarise the legal requirements for financial management of organisations.

· Describe the purpose of financial policies and procedures in an organisation.

Interpreting Financial Reports

Profit and Loss Statement

A Profit and Loss Statement is, perhaps, the most important financial statement and may also be known as:

· Income and expenditure statement.

· Operating statement.

· Revenue statement.

· Monthly profit and loss report.

This statement shows all of the income and expenditure during a specified period usually a month, a quarter or fiscal year of the organisation’s operations. This means everything that the organisation received and spent.

It also shows how much was budgeted for each item, that is, how much money is put aside to be spent or how much money the organisation thought it would receive.

7.1. Profit and Loss Statements

Terms used in the Profit and Loss Statement:

|

Account Name |

Each goal identified by the organisation has its own separate funding. The funding monies are put into a separate account and given their own account name. |

|

Selected Period |

This will indicate the period of time when the figures were calculated. This usually occurs on a monthly basis. |

|

Year to Date |

The total amount for the whole year. |

|

Budget |

The estimated amounts that the Committee thought they would spend on this item. |

|

Actual |

The amounts actually spent by the organisation. Having the Budget column next to the Actual column allows a committee to immediately see whether they have overspent on an item. If the Budget amount is kept separate from the Actual amount, it is less likely that problems will be seen. |

|

Income |

The money the organisation receives or is shortly due to receive. In this case money is being received from a grant, membership fees, donations, some bank interest and wages recovery. Another term often used instead of income is Revenue. |

|

Total Income |

If all the figures under Income are added together it will equal this number. |

|

Expenses |

Everything that has been spent on this project or committed to be spent in this period. In this case money has been spent on advertising, bank charges, catering etc. Expenses can also be known as Expenditure. |

|

Cost of Sales |

Cost of sales (COS) represents all the costs that go into providing a service or product to a customer. It may also be called cost of goods sold (COGS). |

|

Total Expenditure |

The total amount spent in expenses. |

|

Net Profit or Loss |

The most useful number to look at. This is often referred to as “the bottom line.” It says how much there is left after deducting all the expenses from the income or revenue. If too much has been spent the number may have a minus sign in front of it or have brackets around it. For example: ($5,366) |

If the organisation has gone over budget for a selected period too much money has been spent or less money has come in than was expected. If this is the case the Board would ask for an explanation. Perhaps there is money due to come in, but without asking no one will know whether there is money available or you are about to go out of business.

Another word for loss is, Deficit. They both mean the same thing.

Net Loss may also be represented as Net Deficit.

Please see below for an example of a Profit and Loss Statement:[1]

Example Profit and Loss Statement

|

Joe's Motorbike Tyres |

|||

|

Profit and Loss Statement |

|||

|

For the Period ended Year One |

|||

|

Income |

|||

|

|

Sales |

$52,000 |

(1,000 tyres @ $52 each) |

|

|

Total Sales |

$52,000 |

|

|

Cost of Goods Sold |

|||

|

|

Opening Stock |

0 |

|

|

|

Stock Purchases |

$34,320 |

|

|

|

Less Closing Stock |

$3,120 |

|

|

Total Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) |

$31,200 |

(see note below) |

|

|

Gross Profit |

$20,800 |

||

|

Expenses |

|

||

|

|

Advertising |

$500 |

|

|

|

Bank Service Charges |

$120 |

|

|

|

Insurance |

$500 |

|

|

|

Payroll |

$13,000 |

|

|

|

Professional Fees (Legal, Accounting) |

$200 |

|

|

|

Utilities & Telephone |

$800 |

|

|

|

Other: Computer Software |

$480 |

|

|

|

Expenses total |

$15,600 |

|

|

Net Profit before Tax |

|

$5,200 |

|

Note: Cost of Goods Sold Calculation: |

||

|

Towards the end of the year, Joe manages to purchase 100 more tyres on credit from his supplier for an order in the new year. This leaves him with $3,120 of stock on hand at the end of the year. |

||

|

Joe’s Cost of Goods Calculation |

||

|

Opening Stock |

Nil |

(1100 tyres @ $31.20 each) |

|

Add Stock Purchased during the year |

$34,320 |

|

|

Equals Stock available to sell |

$34,320 |

|

|

Less Stock on hand at the end of year |

$3, 120 |

(100 tyres @ $31.20 each) |

|

Cost of Goods Sold |

$31,200 |

|

|

Where a business is a service business, that is, you are selling services, not goods or products, then the profit and loss statement will generally not have a cost of goods sold calculation. In some instances, where labour costs can be directly attributed to sales, then you may consider including these costs and a cost of goods (services) sold. |

||

7.2. Balance Sheet

Balance Sheet may also be known as Statement of Financial position. The Balance Sheet shows the organisation’s complete financial position by detailing the organisation’s total Assets, Liabilities and Equity.

Terms used in the Balance Sheet:

|

Assets |

The land, buildings, cars, equipment and cash that the organisation owns. |

|

Liabilities |

The debts, staff leave entitlements, overdrafts and loans that an organisation owes or is liable to pay in the future. This includes any future expenses that need to be paid or is owed to the bank. |

|

Equity |

Any additional funds can be placed in reserve for important expenditure in the following year if funding bodies allow. This could be retained earnings, which means money set aside for future use. |

|

Total Equity |

The total amount an organisation is worth. The total equity of an organisation will always balance with the Net Worth. |

|

Net Worth |

What the organisation is worth. The amount of money that the members have invested in the organisation. If you take away what the organisation owes (liabilities) from what it owns (assets) the result is the net worth. |

This report always needs to balance, which is why it is known as a balance sheet.

Some organisations only look at the Balance sheet on a yearly basis as part of their annual audit report, but it is best to review the Balance sheet more often if possible. It helps the Board stay informed about the organisation’s overall performance.

An example of a Balance Sheet:[1]

|

Joe’s Motorbike |

|

|

|

|

Balance Sheet |

|

|

|

|

As At end of year One |

|

|

|

|

Current Assets |

|

|

|

|

Cash |

$5,100 |

|

|

|

Debtors |

$18,000 |

|

|

|

Stock |

$3,120 |

|

|

|

Total Current Assets |

|

$26,220 |

|

|

Non-current Assets |

|

|

|

|

Computer |

$5,500 |

|

|

|

Store Fit Out |

$8,100 |

|

|

|

Office Equipment |

$15,000 |

|

|

|

Total Non-current Assets |

$28,600 |

|

|

|

Total Assets |

|

$54,820 |

|

|

Current Liabilities |

|

|

|

|

Credit Card |

$5,500 |

|

|

|

Creditors |

$4,120 |

|

|

|

Total Current Liabilities |

$9,620 |

|

|

|

Non-current Liabilities |

|

|

|

|

Total Non-current Liabilities |

|

|

|

|

Total Liabilities |

$9,620 |

|

|

|

Net Assets |

|

$45,200 |

|

|

Shareholders’ Equity |

|

|

|

|

Owners’ Funds |

|

$40,000 |

|

|

Current Year Profit |

|

$5,200 |

|

|

Total Shareholders’ Equity |

|

$45,200 |

|

7.3. Statement of Cash Flow

The Statement of Cash Flow indicates the flow of cash within an organisation and assists in planning how and when money can be spent.

Cash Flow is essential for the survival of the organisation. Without cash an organisation can get into financial difficulty very quickly and will not be able to pay its bills.

The Statement of Cash flow enables an organisation to budget for the future, to foresee any critical periods when funds might be limited. It can also assist in determining if a large cash outlay on capital expenditure is affordable or whether it would be more appropriate to lease an item.

Terms used in statement of Cash Flow

|

Expenditure |

The amount the organisation has spent during the month. |

|

Balance |

The amount that is left to be spent. This amount can be carried over to the next month and spent then instead. |

|

Brought Forward |

The balance amount may be carried over to the next months and spent then instead. |

|

Income |

The money the organisation receives or is shortly due to receive. In this case money is being received from a grant, membership fees, donations, some bank interest and wages recovery. Another term often used instead of income is Revenue. |

8. Legal Requirements for Financial Management of Organisations

Companies

A company must keep up-to-date financial records that correctly record and explain transactions and the company’s financial position. Larger companies have additional obligations to lodge financial reports with ASIC.

Generally, companies need to lodge financial reports when:

- There are large sums of money involved.

- The public has invested in the company, or

- The company exists for charitable purposes only and is not intended to make a profit.

All companies must keep some form of written financial records that:

· Record and explain their financial position and performance, and

· Enable accurate financial statements to be prepared and audited.[1]

8.1. Co-operatives

Co-operatives must keep written financial records that correctly record and explain their transactions and financial position and performance. The records must enable financial statements to be prepared and audited.

Financial records must be retained for seven years after the transactions covered by the records are completed. If kept in an electronic form the records must be able to be converted into hard copy within a reasonable time.

Reporting Requirements

Different reporting requirements apply for small and large co-operatives.

Co-operatives that are disclosing entities [1]have additional reporting requirements and should consult their legal or financial adviser regarding these obligations.

Determining if you are a small Co-operative

A co-operative is small if it satisfies at least two of the following criteria:

- The consolidated revenue of the co-operative and the entities it controls (if any) is less than $8 million for the financial year.

- The value of the consolidated gross assets and the entities it controls (if any) is less than $4 million at the end of the financial year.

- The co-operative and the entities that it controls (if any) has fewer than 30 employees at the end of the financial year.

The co-operative must also have:

- No securities on issue to non-members during that year other than securities issued to former members on the cancellation of their membership; or

- Not issued shares to more than 20 members in a financial year. Or if it is has done this, the amount raised by issuing those shares does not exceed $2 million.

Co-operatives that do not meet the above criteria are large co-operatives.

Small Co-operatives – Financial Reporting

Each financial year, a small co-operative must prepare a report for its members containing:

- An income and expenditure statement setting out the appropriately classified individual sources of income and individual expenses incurred in the operation of the co-operative.

- A balance sheet, including appropriately classified individual assets and liabilities of the co-operative.

- A statement of changes in equity.

- A cash flow statement is required if the co-operative and any of its controlled entities has consolidated revenue of $750,000 or greater, or if the value of the consolidated gross assets is $250,000 or greater.

The financial statements must present a true and fair view of the co-operative’s financial position, performance and cash flows. They must also include:

- Comparative figures for the previous financial year.

- A statement of significant accounting policies.

An audit or review of a small co-operative’s financial statements and /or additional financial reports, may be required if it is:

- Specified in the co-operative’s rules.

- Requested by its members or the Registrar under the Co-operatives National Law.

Small co-operatives need to report to members within five months of the end of the co-operative’s financial year.

Small co-operatives must lodge a C12 Annual return form within five months after the end of their financial year.

Large Co-operatives – Financial Reporting

Each financial year, a large co-operative must prepare and present to its members:

- The financial report for the year.

- The Board of Directors’ report for the year.

- An independent auditor’s report on the financial year.

OR

- A concise report.

The financial report must be prepared in accordance with the Australian Accounting Standards. It must include the co-operative’s:

- Income statement.

- Balance sheet.

- Statement of changes in equity.

- Cash flows statement.

- Board of Directors’ declaration.

- Notes to the financial statements. These must include:

- Notes required by the accounting standards.

- Disclosure required by the National Regulations.

- Any other information necessary to give a true and fair view.

A concise report consists of:

- A concise financial report in accordance with accounting standards.

- The Board of Directors’ report for the year.

- A statement by the auditor that the financial report has been audited and whether the concise financial report complies with the relevant accounting standards.

- A copy of any qualification in the auditor’s report and

- A statement that the report is a concise report and a full report is available upon request and free of charge.

Large co-operatives need to report to members within five months after the end of the financial year.

Large co-operatives must lodge a C13 Annual Report Large Cooperative form, within five months after the end of their financial year.[2]

[1] A business entity is the legal structure of a business, which can be a sole trader, partnership, or company, among others.

8.2. Associations

Associations must keep records that correctly record and explain their financial transactions and financial position. Where any of the financial records are kept in a language other than English, an English translation must also be kept with the documents.

Tier 1 and Tier 2 Associations

An association's reporting obligations under the Associations Incorporations Act 2009 (the Act) is based on its status as either a Tier 1 (large) or Tier 2 (small) association.

Tier 1 Associations are those whose:

- Total revenue as recorded in the income and expenditure statement (i.e. gross receipts) for a financial year is more than $250,000 or

- Current assets* are more than $500,000.

Before the Annual General Meeting (AGM)

As soon as practical after the end of the association’s financial year the committee must:

- Prepare financial statements in accordance with Australian Accounting Standards. See information below on Complying with Australian Accounting Standards.

- Arrange for the statements to be audited in time for submission to members at the AGM.

- Consider the financial statements and confirm that they provide a true and fair view of the association’s financial performance. It is good practice to record this confirmation in the minutes of the committee meeting.

- Ensure the AGM is held within 6 months of the end of the financial year.

At the Annual General Meeting (AGM)

The committee must:

- Arrange for the financial statements and auditor’s report to be submitted to the meeting.

- Ensure a copy of the financial statements, auditor’s report and a record of any resolution passed concerning the statements or auditor’s report is included in the minutes of the AGM.

After the Annual General Meeting (AGM)

Within 1 month following the AGM the committee must lodge with NSW Fair Trading*:

- The Annual summary of financial affairs.

- A copy of the audited financial statements.

- A signed and dated auditor’s report.

- A copy of the terms of any resolution passed at the AGM concerning the statements and audited report.

- Payment of the prescribed lodgement fee.

Tier 2 Associations are those whose:

- Total revenue as recorded in the income and expenditure statement (i.e. gross receipts) for a financial year is $250,000 or less, and

- Current assets* are $500,000 or less.

Before the Annual General Meeting (AGM)

As soon as practical after the end of the association’s financial year the committee must:

- Prepare financial statements that include:

- An income and expenditure statement that sets out appropriately classified individual sources of income and individual expenses incurred in the operation of the association.

- A balance sheet that sets out current and non-current assets and liabilities.

- A separate income and expenditure statement and balance sheet for each trust for which the association is the trustee, and

- Details of any mortgages, charges and other securities affecting any property owned by the association.

- Consider the financial statements and confirm that they provide a true and fair view of the association’s financial performance. It is good practice to record this confirmation in the minutes of the committee meeting.

- Ensure the AGM is held within six months of the end of the financial year.

Audit of financial statements

NSW Fair Trading does not require Tier 2 association’s financial statements to be audited however, it may direct an association to conduct an audit and request an auditor’s report.

An association’s constitution or funding arrangements may require an audit.

At the Annual General Meeting (AGM)

The committee must:

- Arrange for the financial statements to be submitted to the meeting.

- Ensure a copy of the financial statements and a record of any resolution passed concerning the statements is included in the minutes of the AGM.

After the Annual General Meeting (AGM)

Within 1 month following the AGM the committee must lodge with Fair Trading*:

- The Annual summary of financial affairs.

- Payment of the prescribed lodgement fee.

The financial statement presented to members at the AGM and other documents such as the minutes, agenda and notice of meeting are not required to be lodged, unless specifically requested by Fair Trading.[1]

8.3. Indigenous Organisations Incorporated Under the CATSI Act

Responsibility for reporting

Corporation directors, as well as secretaries of large corporations, are responsible for ensuring their corporation meets its reporting obligations. They must ensure the corporation keeps appropriate financial records that enable true and fair financial statements to be prepared; the corporation prepares and lodges appropriate reports and within the appropriate timeframes; and that the information in the reports is true and correct.

All corporations must lodge reports with the Registrar every year within six months of the end of the corporation’s financial year. Most corporations end their financial year on 30 June which means their reports are due between 1 July and 31 December.

Types of reports

The reports each corporation is required to prepare and lodge vary depending on its registered size and income.[1]

|

Size and Income |

Reports Required |

|

Small corporations with a consolidated gross operating income of less than $100,000. |

1. General report only. |

|

Small corporations with a consolidated gross operating income of $100,000 or more but less than $5 million. |

1. General report. 2. Financial report and Audit report OR Financial report based on reports to government funders (if eligible). |

|

Medium corporations with a consolidated gross operating income of less than $5 million. |

1. General report. 2. Financial report and Audit report OR Financial report based on reports to government funders (if eligible). |

|

Large corporations or any size corporation with a consolidated gross operating income of $5 million or more. |

1. General report. 2. Financial report. 3. Audit report. 4. Directors’ report. |

9. Financial Policies and Procedures for Organisations

Financial management is not only about understanding the financial information in the organisation and using this information to improve organisational operations, it is also about ensuring that the right policies and procedures are in place to ensure that the financial information the organisation is using is accurate and can protect the investments within the organisation. For complete financial management of the organisation, good financial controls should be present.

A financial control is a procedure that is implemented to detect and prevent errors, theft or fraud, or policy non-compliance in a financial transaction process. Financial control procedures can be implemented by either an individual or as part of an automated process within a financial system.

Benefits of financial controls

By implementing good financial controls, the organisation will benefit by understanding the financial position of the organisation:

· Providing accurate financial information that can be used by those responsible for the operations of the organisation (e.g. Sales numbers can be provided to sales representatives to monitor targets and budgets).

· Enabling organisations to make informed decisions on budgets and spending.

· Providing documentary proof for compliance requirements (e.g. GST calculations).

· Setting standards and informing all persons within the organisation of these standards through reporting.

To support the preparation and reporting of financial information, financial controls that consist of policies and procedures that align with the objectives of the organisation are vital. The board or management committee also have a role in good financial management. They must know how to oversee the finances of the organisation. This means that they must understand the financial information that is prepared and presented. They are ultimately responsible for transparency, accountability and stewardship of all financial matters to ensure that the social objectives of their community organisation are met.[1]

A financial policy is a formal description of how your Board handles issues like paying down debts, rationing cash reserves, who can handle money and how you deposit and withdraw funds. The goal of financial policies is to protect donor funds, promote financial stability and hold the board and executives accountable for financial expenditures and oversight.

Financial policies are useful as a guideline for accepting gifts, dividing duties, authorising financial transactions, obtaining proper receipts and disbursing funds.

Your financial policies may be as broad or detailed as you think you need. It’s a good idea to review your financial policies (and all your policies) at least annually and revise them as you see fit. You can always revise your policies by a board vote if you run into a situation that prompts you to change the policy right away.

Who establishes your financial policies? Ultimately, your Board is responsible for developing, implementing and overseeing financial policies. It is common for Boards to take up the task, but your Board could just as easily delegate the task to a financial planning committee.

The individual or group that is developing your financial policies should keep the following key components of financial policies in mind:

- Assigning authority for financial actions and decisions.

- Delegation of authority for financial decisions and transactions to staff and volunteer leaders.

- Procedures for conflicts of interest and insider transactions.

- Procedures for authority to spend funds and write checks.

- Procedures for managing payroll.

- Assignment of authority to enter into contracts.

- How financial records are to be documented.

While financial policies are the “what” of financial management, financial procedures are the “how”. Financial procedures are a collection of statements that describe how to handle funds. Financial procedures outline how to handle financial practices for things like:

- Receiving and endorsing cheques.

- Documenting cash and preparing cash receipts.

- Storing deposit and withdrawal slips.

- Training staff and volunteers on following financial policies.

- Authorising people to open accounts, sign checks, etc.

- Borrowing funds and establishing lines of credit.

- Detailing prohibited financial practices.

- Handling online payments, petty cash, credit cards and debit cards.

Accounting and reporting are central to an organisation’s financial procedures. Your Board may require or at least, make it a practice to hear a reporting of the organisation’s financial position and statement of activities at every board meeting.

Financial procedures include statements for how to manage:

· Cash flow statements.

· Statement of activities.

· Statement of financial position.

· Reports of assets.[2]

In conclusion you are now introduced the core financial documents that every Board member must understand to effectively govern an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander organisation. We explored the structure and purpose of the Profit and Loss Statement, Balance Sheet and Cash Flow Statement -three essential tools that show how money moves through an organisation, how assets and liabilities are managed and whether the organisation is operating sustainably. Understanding these reports enables Board members to make informed decisions, identify risks early and ensure the organisation remains financially healthy.

You now have knowledge of the legal requirements for financial management across different organisational structures, including companies, co-operatives, associations and corporations incorporated under the CATSI Act. Each structure has specific reporting, record-keeping and auditing obligations that Board members must comply with to meet regulatory standards and maintain transparency. Being aware of the importance of financial policies, procedures and internal controls - these systems protect the organisation from errors, fraud and non-compliance, support accurate reporting and reinforce the Board’s responsibility for accountability and custodianship of community resources.

Together, these skills and knowledge areas equip you with the financial literacy and governance capability needed to contribute confidently and responsibly to

[1] https://www.cpaaustralia.com.au/-/media/project/cpa/corporate/documents/tools-and-resources/not-for-profit-and-public-sector/not-for-profit/financial-management-nfp-organisations.pdf?rev=1eed68f994ba43ba9ee26be2a059e639

[2] https://In www.boardeffect.com/blog/sample-financial-policies-procedures-for-nonprofits/