M2 - Learner Manual

9. The Stolen Generation

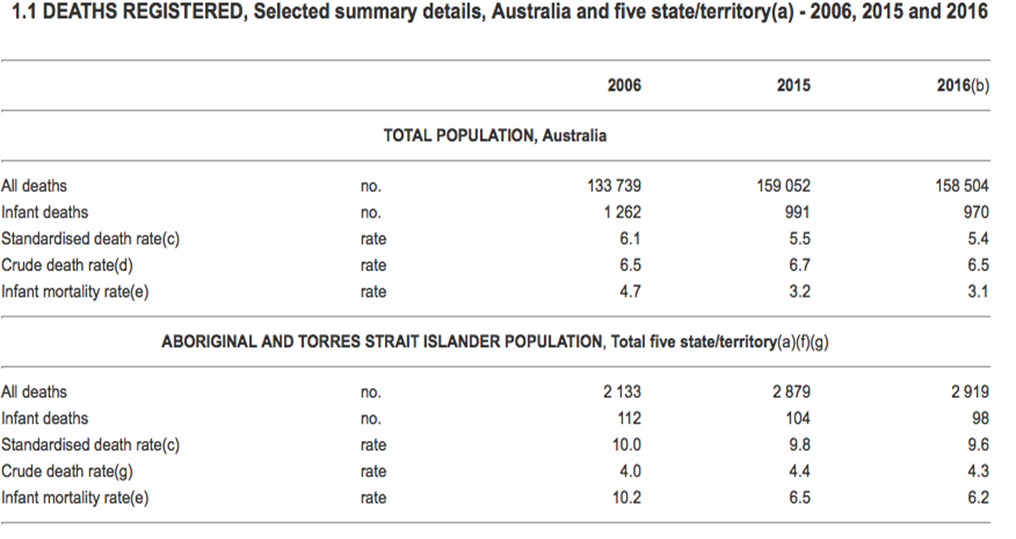

9.11. Mortality rates

* Population figures supplied by the Australian Bureau

of Statistics

Infant Mortality and Life Expectancy

Between 2014-2016, Indigenous children aged 0-4 were more than twice as likely to die than non-Indigenous children. In the Northern Territory, Indigenous infant mortality was 4 times higher than the national rate. [2]

From birth, Indigenous Australians have a lower life expectancy than non-Indigenous Australians:

Non-Indigenous girls born in 2010-2012 in Australia can expect to live a decade longer than Indigenous girls born the same year (84.3 years and 73.7 years respectively).

The gap for men is even larger, with a 69.1-year life expectancy for Indigenous men and 79.9 years for non-Indigenous men. [3]

Indigenous women also experience approximately double the level of maternal mortality in 2016. [4]

Physical and Mental Health

There's a strong connection between low life expectancy for Indigenous Australians and poor health.

In 2016, Indigenous children experienced 1.7 times higher levels of malnutrition than non-Indigenous children. [5]

In 2014-15, hospitalisation rates for all chronic diseases (except cancer) were higher for Indigenous Australians than for non-Indigenous Australians (ranging from twice the rate for circulatory disease to 11 times the rate for kidney failure). [6]

Just under half (45%) of Indigenous people aged 15 years and over said they experienced disability in 2014–2015, compared to 18.5% of the whole Australian population in 2012. [7]

Other major concerns include mental health, suicide and self-harm.

In 2015, the Indigenous suicide rate was double that of the general population. Indigenous suicide increased from 5% of total Australian suicide in 1991, to 50% in 2010, despite Indigenous people making up only 3% of the total Australian population. The most drastic increase occurred among young people 10-24 years old, where Indigenous youth suicide rose from 10% in 1991 to 80% in 2010.

33% of Indigenous adults reported high levels of psychological distress in 2014-15, and hospitalisations for self-harm increased by 56% between 2004-05 and 2014-15.